Hannah Kent Schoff

Hannah Kent Schoff, a resident of Powelton, was a progressive advocate for the health and wellbeing of the nation’s children.

Hannah Kent Schoff was an activist social worker and pioneer in the movement to establish juvenile courts in the nation’s cities at the turn of the last century. She also made a lasting mark as longstanding president of the children’s- advocacy organization that founded the national PTA.

Background and Advocacy for Juvenile Courts

Hannah Kent was born in 1853 in Upper Darby, PA. In 1873, she married Frederick Schoff, with whom she would raise seven children at 3418 Baring Street in Powelton. Frederick operated Stow Flexible Shaft Co., which he had co-founded with George Burnham, Jr. (214 N. 34th Street). Their flexible shafts and variable speed motors were widely used in industry and made possible such innovations as the dentist’s drill. Frederick was a member of the Church of the New Jerusalem (Swedenborg), the Union League, and the Sons of the Revolution.

Yet Hannah was by far the more interesting of the two. In 1899, she read about an eight-year-old girl convicted of arson. The girl’s mother had died when she was two, and she was placed in an orphanage and later put to work in a boarding house that she set fire to. A front-page article in the Philadelphia Inquirer Sunday Magazine of 16 March gave the girl’s name—Annie McClain— and included a sketch of her. The reporter stated that experts “acknowledged her to be one of the most clever and accomplished of natural-born criminals.” She was variously described as a pyromaniac, kleptomaniac, prevaricator, and child-fiend. Phrenology (a pseudo-science defined as “the detailed study of the shape and size of the cranium as a supposed indication of character and mental abilities”) showed that “three prominences of the back head [which] form the basis of our selfish properties, are well developed” on the girl. The expert consensus was that Annie was a “degenerate.” Having confessed to arson, she was sentenced in a regular court to a House of Refuge along with adults. Hannah Schoff interceded on Annie’s behalf and convinced the judge to place her in a good home.

Schoff credited this incident with setting her on a twenty-five-year course to change the court system’s treatment of “wayward” children and to focus attention on strengthening families and educating mothers. She declared that “there is no criminal class of children . . . their faults come from faults of schools, church, and State” (Philadelphia Inquirer, 28 November 1911). She repeatedly stated that children who commit crimes “are not criminals. They are children who, by loving intelligent help at this time, may have their lives turned into the right direction” (Philadelphia Inquirer, 3 November 1912). She urged the legal system, schools, and churches to develop approaches to supporting these children and their families.

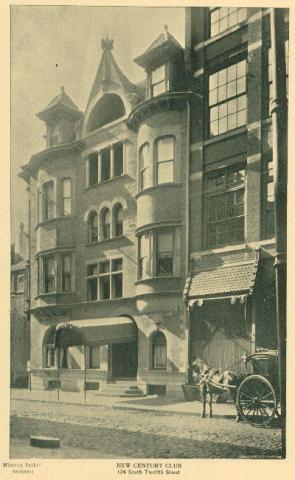

Schoff’s first step was to set about reforming the treatment of juveniles in the criminal justice system in Philadelphia. Working with other members of the New Century Club in Philadelphia, she began the campaign that led in 1901 to the establishment of a juvenile court system (only the nation’s second, after Chicago’s, established in 1899), separate detention homes (in place of jails), and a system of (volunteer) probation officers. During the first eight years, she observed almost every session of the new court. She pushed for a similar system in Pittsburgh and for the whole Commonwealth. One of the New Century Club members who worked with her on this was Mrs. Elizabeth W. Garrett (3613 Powelton Avenue). Schoff also assisted successful efforts in other states, including Connecticut, Louisiana, and Idaho, as well as in Canada, where she was the first woman ever invited to address the Canadian Parliament.

Stewardship of the National Congress of Mothers

Schoff helped form the National Congress of Mothers in 1897. She served as this organization’s president from 1902 to 1920, during which time its name was changed to the National Congress of Mothers and Parent-Teacher Associations. As Schoff explained in a 1916 essay for the Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, her organization’s purpose was “studying and promoting every phase of child welfare” and advancing “educated parenthood . . . [through] home education.” Schoff is credited with forming the PTA as a national organization with many state affiliates; by 1917, the National Congress counted more than 100,000 mothers under its umbrella. Schoff founded the organization’s journal, Child Welfare (later National Parent-Teacher) and edited it from her home. In step with the 1910s movement toward the “wider use of schools,” Schoff’s organization called for opening school buildings for parent education and recreation activities, in concert with the PTA.

A major focus of the National Congress of Mothers was preventing children from falling into a life of crime. For example, they opposed a complete ban on child labor on the grounds that some children should work to keep themselves out of trouble. Schoff oversaw a large-scale investigation into the childhood circumstances that led to criminal incarceration. Her study of 8,000 questionnaires led to her book The Wayward Child (1915). In it, she wrote that over the years she had been in touch with the so-called incorrigible children and she had seen many who were regarded as hopelessly wicked respond to the love and care given them.

Widely regarded as a social progressive, Schoff was in fact very “Victorian” in her view of childrearing as “the highest, holiest duty of womanhood.” Her conservative view of “women’s sphere” and her impatience with suffragettes put her at odds with the more radical feminists of her day. For example, in an impromptu speech in Harrisburg in 1913, she declared, “With so much work waiting to be done, so many great and good undertakings that fall flat for lack of competent persons to assume control, it does not seem to me that our women of today may better devote themselves to the things which may be accomplished rather than bewail the fact that they are hampered in their actions for civic good by the lack of a vote.”

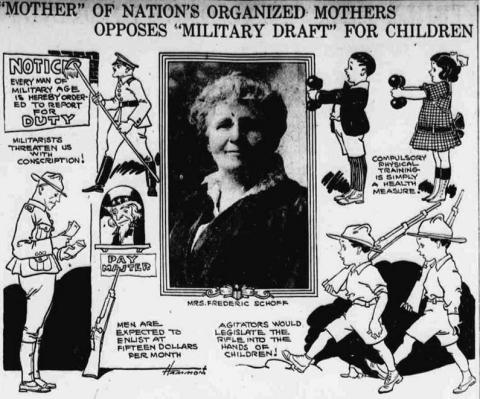

Hannah Schoff was widely recognized as a national leader on many of the issues of her day involving the health and well-being of children. For example, several days before America’s entry into World War I, as reported in the Philadelphia Inquirer (3 April 1917, Schoff, declaring herself “not a pacifist,” denounced universal military training that would involve putting weapons into the hands of children. An article in the New York Tribune in 1917 on child nutrition referred to “the great progressive army of mothers and educators organized under the leadership of Mrs. Frederick Schoff.” That same year, the Philadelphia Inquirer hailed her as the “‘mother’ of the nation’s organized mothers.”