Advanced Search

Paul Robeson as the title character & Uta Hagen as Desdemona, in the New York City Theater Guild’s Broadway production of Othello (1943–1944). José Ferrer, Hagen’s spouse at the time, played the villain Iago. Broadway would be off limits to Robeson in the Cold War era, the consequence of his persecution by the federal government and vilification in mainstream media.

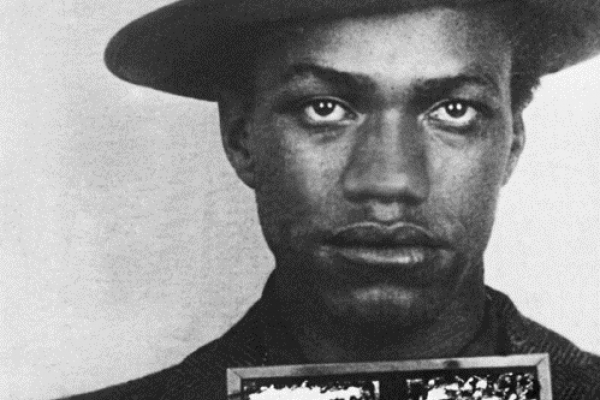

A Boston police mugshot of Malcolm Little following his arrest for larceny.

Some 200 gardens measuring 25 by 25 feet are laid out across this tract (formerly Passon Field) for Victory Gardens.

The Fairmount Park Trolley Line, built and operated privately by the Fairmount Park Transit Company, carried passengers to Woodside Park, among other destinations in Fairmount Park West. This excerpt from a 1944 Philadelphia Transportation Company Map shows Woodside Park near the intersection of Ford and Monument roads, with the Belmont Reservoir in view on the map. The Woodside Station foregrounds the amusement park. The Fairmount Park Trolley operated here until 1946, when the line ceased operation and was dismantled.

West 125th St. in 1946 looking west from Seventh Ave., Harlem, New York City, with the famous Apollo Theater in the right-background. Paul Robeson and Malcolm X felt at home in Harlem. King confronted institutional racism in Harlem in the wake of the 1964 Harlem riot. Today’s 125th St. is Martin Luther King Jr. Blvd; Seventh Ave. is designated Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Blvd., although Seventh Ave. is still commonly used.

The Pennsylvania Working Home for Blind Men operated fitfully through the first three-quarters of the 20th century, failing to stabilize its finances and standing aloof from changes in the education and vocational training of blind citizens.

Paul Robeson (second from left) joining members of the Baltimore chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in a picket line in front of Ford's Theater, Baltimore, to protest the theater's policy of racial segregation. Robeson, who was a quarter-century older than Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X, set an example of civil rights militancy that was all but forgotten during the “heroic age” of the Civil Rights Movement.

Paul Robeson (second from left) joining members of the Baltimore chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in a picket line in front of Ford's Theater, Baltimore, to protest the theater's policy of racial segregation,

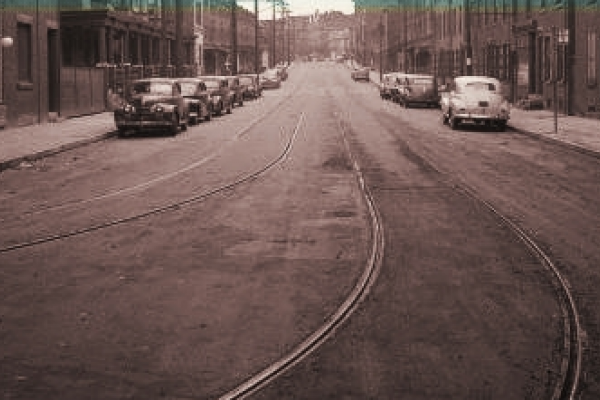

This vintage city photo looks west from 36th St. with the Market St. Elevated in view. The El cast its shadow over West Philadelphia’s working class neighborhoods from its opening in 1907 to its dismantling in 1956, following the 1955 opening of the Market St. subway tunnel. The tunnel excavation itself took seven years and was a blighting factor in the Black Bottom.

The view is north from Market along 36th St. City officials took this and other photos from 1948 into the 1950s during construction of the Market St. subway tunnel.

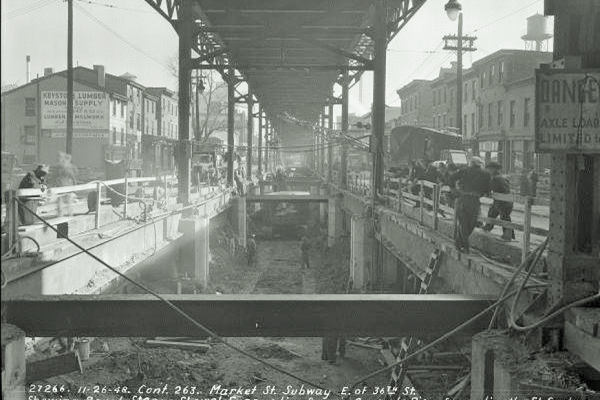

This photo shows the excavation of the Market Street tunnel at 36th Street. Tunnel digging had harmful effects for the surrounding blocks, in this case a majority-African American neighborhood known locally as the Black Bottom.

Construction of the Market Street rapid transit/subway tunnel began around 1923 at 24th Street. By 1932 the four-lane tunnel under the Schuylkill River had only reached 32nd Street, at which point construction was halted and the tunnel sealed. The Great Depression and Second World War provided ample reasons for postponing the project. Construction began anew in 1948.