The Boothroyd and Goodyear Families of Mill Workers and the West End Mill

The Boothroyd and Goodyear families of West Philadelphia’s West End sent their children into West End Mill, a producer of cotton fabrics and some woolens, in the decades around the turn of the 20th Century.

John Boothroyd was a weaver in a cotton mill along Cobbs Creek. He was born in 1822, probably in the English village of Boothroyd in Dewsbury, West Yorkshire, a mid-sized mill town. He probably came from a family of weavers, and he arrived in America as a skilled worker. In 1860, he was living in Springfield, Pennsylvania with his wife, Mary, their five children, and his mother-in-law. Mary was born in Scotland. By 1870, they had moved to the West End Mill area of what is now Cobbs Creek, where he worked at the West End Mill. By now John and Mary had eight children. The four older girls (aged 14 to 23) and son, John (11), were also working as weavers. The three younger children were Joseph (9), Thomas (5), and Emma (2).

The West End Mill was built in 1866 at S. 64th and South St. (now Cedar Ave.) on land that is now in the middle of Cobbs Creek Park. The mill was built by John Ashworth. From Ashworth the property transferred to Henry S. Henry, a wealthy cotton-waste dealer. When Henry died in 1877, the mill was inherited by his young sons, Henry S. Henry Jr. and David H. Henry.

The mill primarily produced cotton fabrics and some woolens. The main building was four stories high and built of stone. It included machinery for carding raw cotton or wool into separate fibers, about 3,000 spindles for spinning the fibers into yarn, and about two dozen looms for weaving the yarn into fabrics. A smaller building was used for dyeing and packing the finished product. A separate, long, one-story building was devoted solely to weaving. An engine and boiler room provided the power to run the machines. The air was full of dust, and there were bails of raw cotton, lint waste, and finished products that made fabric mills notoriously susceptible to fire. The West End Mill had extensive facilities for fighting a fire. Yet for all the precautions taken, it suffered a severe fire in 1876, caused by overheating of the machinery, with a reported loss of $195,000. Fortunately, all 220 employees escaped unharmed, which was not always the case in mill fires. The mill returned to full operation quickly.

The workers and their families lived nearby in the West End neighborhood, which was built on land owned by the Henry family. The area around West End, itself isolated, was rural and undeveloped. In 1880, West End’s population was 611, more than 37 percent of the total population of the area that is today comprises the large Cobbs Creek neighborhood (bounded east–west by 52nd St.–Cobbs Creek Parkway, Market St.–Baltimore Ave.). The 1880 census lists 214 cotton mill workers and 9 woolen mill workers in the West End neighborhood. Henry and David Henry, owners of the mill, also lived in the area: Henry next to the mill and David at S. 62nd and South St. (Cedar Avenue). Henry was 24, David was only 21, and David’s wife was 22.

The Boothroyd family was typical of the families that lived and worked at West End. In 1880, 80 percent of the population aged 15–19 worked in the mill. After that age, the proportion of men working in the mill dropped off slowly to about 40 percent over age 45. Like Mary Boothroyd, few married women worked—only about one-in-eight married women worked in the mill.

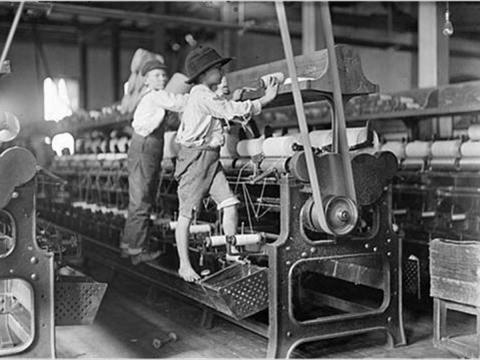

Work in the mill started at an early age in West End; nearly all the boys from mill families—young John Boothroyd was no exception—arrived there by age 11. This was not typical of families of cotton- and wool-mill workers elsewhere in Philadelphia, where, as a rule, boys in mill-worker households were able to stay in school for a few more years and find alternative sources of work if mill work didn’t appeal to them. Such was West End’s isolation that there were few alternative work opportunities—one 17-year-old boy worked in a bakery and one 18-year-old worked in a store. Girls in mill-worker families in West End stayed in school about a year longer than their brothers, but like the Boothroyd girls, most were in the mill by age 12. Again, this was not typical in Philadelphia mill families: girls who entered the mills did so a year or two later than their West End counterparts.

Work in the mills was nasty. There was the constant clacking of the looms and the noise of the steam engines. The air was generally kept very warm and moist to keep the yarn from breaking. Cotton dust was everywhere. However, putting the whole family to work paid off for the Boothroyds: In 1883, they were able to purchase 6142 Cedar Avenue, which the family would own until 1949 – a total of 66 years.

The tradition of working in the mills was continued by all of John and Mary’s children. In 1880, John, age 21, was still living with his parents and working as a cotton weaver. In 1880, the youngest brother, Thomas, age 13, was also working in the mill, but was too young to work as weaver. Both John and Thomas spent their lives working in mills. Two of the Boothroyd’s daughters, Catherine and Mary, also spent their lives working in mills. In 1910, Thomas, Catharine, and Mary lived with their sister, Emma, and her husband in the family home at 6142 Cedar only two blocks from the West End factory. When John Boothroyd died in 1920 at age 60, he had never married and had spent his life working in the mill. Thomas Boothroyd died in 1943. He was a retired mill worker and had never married. Emma was the youngest of the Boothroyd’s children. She married a paper hanger, Henry Ness, but didn’t entirely escape the mill. She probably worked there from age 11 until she married at 28. She and Henry divorced, and they apparently were childless.

Lydia Boothroyd, the fourth daughter, married the weaver Napolean [sic] Goodyear, who worked at the West End Mill. In 1900, Napolean and their three sons, Howard, James, and Robert, ages 14, 17, and 19, respectively, were all working there. As previously noted, mill work was hard, and it didn’t pay well. In 1912, wages for weavers in Philadelphia were generally in the range of $6–$18 per week, with weaving supervisors earning $20–$30. Son James became a trolley car conductor but died tragically in 1908 at the age of 26.

Howard Goodyear, the oldest son, never married and worked in the mill most of his life. In 1940, he was unemployed and living with his mother and one unmarried sister at their home at 6147 Walton Ave. Lydia Boothroyd Goodyear died in 1941 at age 84. Howard died in 1946 at age 65. The third son, Robert Goodyear, married Bridget Foley, the daughter of a dairy farmer in Upper Darby. He became a plasterer. When he died in 1959, he was living at 7 S. 3rd St. in Upper Darby, only 1.6 miles from where he was born.

Two generations of Boothroyd and Goodyear children attended the West End elementary school at 60th and Cedar. In 1880, the building offered a night school for young men. A new, larger building was built in 1903 to supplement the older building—just in time to handle the rapid development of the surrounding area. In 1906, the Board of Health recommended closing the old building. They reported that “the old building is being used for the smallest children, who have to sit in seats where their feet cannot touch the floor; there is no ventilation and the rooms are so dark that gas has to be used or lamps burned, thus depriving the children of badly needed oxygen.” In 1913, the school was enlarged and renamed the William Cullen Bryant School, which is still in use today, serving a low-income, majority-African American neighborhood.

Over time the work force of the West End Mill changed substantially. The number of mill workers increased from just over 200 in 1880 to over 350 in 1900. By 1910, the number was back to about 200 although the mill still reported having 225 looms. The employment of young girls (aged 10–14) had virtually ended by 1900, but the employment of young boys remained constant a few years longer. By 1910, there were only four young girls and no young boys still employed in mill work.

West End Mill was sold around 1907 to the owners of two other cotton and woolen mills. However, the property would be condemned by the City to be incorporated into the new Cobbs Creek Park. It’s not clear exactly when the mill closed. It continued in operation at least through 1913, as the owners advertised for a fireman to run the boilers at night. The mill was probably razed in 1915.

Despite the closing of the West End Mill, there were still many mill workers living in the area. The 1920 census lists 119 mill workers living in the area and there were still about 60 in 1930. By then the whole of what today is the Cobbs Creek neighborhood was fully developed, and the mill had passed into history.

Note on the 1880 Census: In the 1880 census, the area that now comprises the Cobbs Creek neighborhood was wholly covered by enumeration district 578, which also included the area of Angora just below Baltimore Ave. west of 58th St.

Note on Research Methods and Sources: Work on this article began by selecting a mill worker from a randomly selected page in the 1900 census for the enumeration district in Cobbs Creek that included many mill workers. That led to Napolean Goodyear. Historic maps pointed to the West End Mill and the Henry family that owned the area called West End. From there, the genealogy of the Boothroyd, Goodyear, and Henry families was pieced together using data from the censuses of 1870 to 1940, death certificates and other vital records compiled at Ancestry.com. The histories of the West End Mill and the West End School are largely based on information from the Philadelphia Inquirer, tabulations of census data for the area surrounding the mill, and a few volumes of the Hexamer General Surveys.