A Storied Athletic Venue in West Philadelphia: From Passon Field to Pollock Field

An undeveloped tract of land at 48th and Spruce streets became a baseball field that in the early 1930s was home to Black professional and semi-professional baseball teams. In the wartime 1940s, the field was home to hundreds of Victory Gardens. From the 1950s on, it was home to West Philadelphia High School’s football and baseball teams.

BACKGROUND

The story of the athletic field on the block bounded by 48th, Spruce, 49th, and Locust streets is properly viewed in historical context. It is the context of Black baseball at the turn of the last century, when Black entrepreneurs and their ballplayers were denied access to Organized Baseball, as the expanding White major league teams and their subsidiaries (“farm teams”) were known.

The original impetus behind the rise of what would be known by 1940 as Negro Leagues Baseball was the Great Migration of 500,000 of southern blacks in 1916–19. Migrants responded to their lack of social and economic freedoms in the Jim Crow era and the lure of employment opportunities in the industrial North by “voting with their feet.” The early migrants, most of whom were poor and when employed could only find part-time work in menial occupations, looked to baseball for recreation and amusement. And for a few, those good enough to play for wages and, later, salaries, baseball was their employment.[1]

With a Black population of 219,599 in 1930, Philadelphia had a sufficiently large general population to support semi-professional Black and White baseball teams. Yet the Depression left Black baseball enterprises in a perilous financial condition and included one demoralizing failure: the collapse of the Eastern Colored League, of which Darby, PA’s Hilldale team was the strongest.

Yet from the ashes of the Hilldale Club and its ballpark, Hilldale Park, the Black entrepreneur Ed Bolden would assemble the Philadelphia Stars, which joined the newly formed Negro National League (NNL) in 1933.

The new league’s name was adopted from Black baseball entrepreneur Rube Foster’s Negro National League, which operated from 1920 until it folded. The new NNL’s major organizer was Gus Greenlee, the enterprising owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords. Greenlee made a considerable fortune operating a numbers-lottery, yet showed a big heart with generous food distributions to the poor of Pittsburgh’s predominately Black “Hill” district.[2]

Vexing the NNL from the start was Black baseball’s “chronic problem of obtaining suitable home grounds” for games. Ed Bolden found a temporary solution when he obtained a contract from the White baseball entrepreneur Harry Passon to schedule Stars home games at Passon Field. This was the informal name given to the ballfield Passon rented and renovated on the northwest corner of 48th and Spruce streets. It was a name that Passon marketed as his personal brand.[3]

The field appears on the 1927 Bromley map for West Philadelphia. The property belonged to the Eli K. Price Estate,[4] named for the family’s patriarch, a noted nineteenth-century Philadelphia attorney and civic activist. As a state senator, Price had shepherded passage of the Consolidation Act of 1854 through the Pennsylvania legislature—the bill that merged the City and County of Philadelphia.[5] Investment properties Price acquired in Blockley Township were passed down in the family after his death in 1884. By 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression, the rental field was already a popular athletic venue, “formerly called Lit Brothers Field and Elks Field.”[6] How did this massive rectangular block come to be associated with the name of Harry Joseph Passon, a Russian-born immigrant?

HARRY PASSON: AN IMMIGRANT’S TALE

We know only a few details of Harry J. Passon’s early life. He was born to Eva and Joseph Passon in 1897 in Kiev, Russia, the city from which the Passon family—husband, wife, and two boys—emigrated to the U.S. in 1906. They fled Russia in the wake of the infamous 1905 Kiev pogrom. Harry was eight at the time.

According to the 1910 U.S. Census, the Passon family lived in a rental house at 2231 South 7th Street, in South Philadelphia. Joseph, who was literate, worked as a tailor of women’s clothing. In the 1920 U.S. Census we find his 23-year-old son Harry listed as a naturalized citizen. Harry is now living with his parents and six siblings on Porter Street in South Philadelphia and employed as a school teacher (the 1940 Census would show him with two years of college).

In the 1920s, Harry’s life would take a lucrative financial turn. The 1930 Census shows him as owning his own home. At the time, Harry was married to Bessie Greenbaum, a 30-year-old Russian-born immigrant; the couple lived with their three-year old daughter, Dorothy, at 4739 Franklin Street, in north-central Philadelphia.

We take up Harry’s story at this point, when he was making his mark as an entrepreneurial co-founder, and eventually the sole owner, of Passon’s Sporting Goods, a thriving enterprise at 507 Market Street. The business supplied the City’s semi-professional sports teams, especially its homegrown Black and White baseball teams, with attractive, serviceable uniforms and top-quality equipment.

Passon’s Sporting Goods was a catalytic hub for sports organizing in the city. Baseball researcher Rebecca Alpert notes, “Passon’s Sporting Goods was the home base of the Passon Athletic Association, a member of the Amateur Athletic Union. The Union sponsored all the Passon Clubs (baseball, boxing, track and field, and soccer). The store also housed a booking service and served as a place where managers, players, and umpires came to meet and find one another to talk sports, purchase equipment, make deals, and schedule contests.”[7]

For five years in the Depression era, Passon was the exclusive booking agent for the field at the northwest corner of 48th and Spruce streets. He collected scheduling fees from the teams who used the field. Passon Field ballgames frequently pitted White semipro teams against Black teams.

PASSON’S RIVALRY WITH ED BOLDEN

By 1932 Passon had organized a Black professional team, the Philadelphia Bacharachs, an independent team whose home park was Passon Field. In 1933 and 1934, Passon Field was also home to Ed Bolden’s Philadelphia Stars, the Bacharachs’ archrival. To spur citywide interest in his baseball ventures, Passon upgraded his ballpark with 4,000 new seats, mounted arc lights for night baseball, and built a grandstand and a clubhouse.[8]

To Ed Bolden’s chagrin, Passon’s Bacharachs joined the NNL in 1934 as an associate member, “a vague status allowing games with the league and protection against potential raids by league teams in return for 50 percent of the franchise fee.” Quite simply, Bolden believed that Philadelphians wouldn’t support two Black professional teams, and he also disliked Passon. The Philadelphia Stars, a full-fledged founding member of the NNL, was now co-owned by Bolden and the Jewish sports entrepreneur, Ed Gottlieb. Ironically, Gottlieb had been a founding partner in Passon’s Sporting Goods.[9]

The NNL saw its first championship series played in September and early October 1934 at Passon Field. This event pitted the Chicago American Giants against the Stars. The series, which was won by the Stars in seven games, was marred by player assaults on the umpires. It was also complicated by a profitable break for an East-West all-star game played at Comiskey Park in Chicago, which attracted a crowd of 25,000. That event was followed by two four-team doubleheaders at New York’s Yankee Stadium, each of which drew a crowd of more than 20,000. These big-venue games, played in September, involved both Stars and Giants players. By comparison, the Passon Field championship series, drawn out over two months, drew no more than 5,000 fans for any game.[10]

After the 1934 season, Bolden moved his team to Penmar Park at 44th Street and Parkside Avenue. Penmar had a larger seating capacity than Passon Field. Here in the 1940s, a prosperous decade for the National Negro League, the Stars would achieve local prominence and a measure of fame in baseball history through the coverage given them in the leading African American newspapers.

As for the Bacharachs, Passon dissolved his club’s relationship with the NNL and “continued to field the Bacharachs as an independent semi-pro team that still played against [and served as a source of young players for] the Stars and other league teams.” Until the end of the Second World War, the Bacharachs remained a finishing school for players advancing to the NNL, though they no longer played at Passon Field.[11]

It should be noted that a second competitive professional league, the Negro American League (NAL), was formed in 1937. The new league comprised four teams from the Midwest and two from the South as of 1944. From 1942 to 1948, each league’s pennant winner played the other in the Negro World Series. The two leagues groomed the great Black ballplayers who integrated Major League Baseball, famously beginning with Jackie Robinson of the Kansas City Monarchs, who joined the Brooklyn Dodgers in 1947. As is well known, Robinson bravely lighted the way for other Negro Leagues greats.[12]

PASSON’S DEMISE

What became of Harry Passon? We learn from the 1940 Census that Harry and his first wife, Bessie Greenbaum, were no longer married. Harry remarried in 1938, this time to Tille Fastman, age 38, the daughter of Austrian-born immigrants. The final decade of Harry’s life was reportedly marred by his depressive and suicidal tendencies. As Rebecca Alpert tersely notes, “In February 1954 he was found dead in the ammunition vault of his store, a gun at his feet from which one bullet had been fired.”[13]

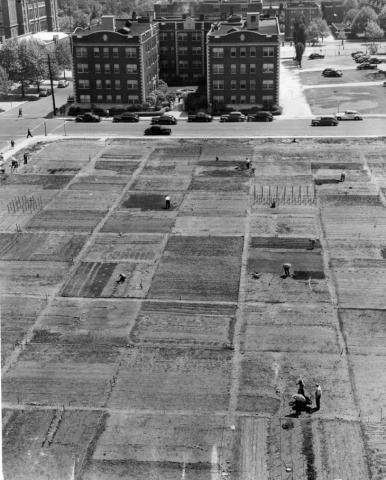

What became of Passon Field after Harry Passon and the Bacharach Giants? During the Second World War, the athletic field was converted for use as the patriotic site of some two-hundred Victory Gardens. After the war, the School District of Philadelphia acquired the venue as the homefield for the West Philadelphia High School Speedboys football and baseball teams. Today it is named Pollock Field.

In 2011, the massive Tudor-Gothic high school building that was long associated with the field closed after a century of operation. In recent years, the venerable structure, which is listed on the U.S. National Register of Historical Places, has been redeveloped as an apartment building. In the fall of 2011, the name West Philadelphia High School was burnished on the façade of a newly built though much smaller building (reflecting sharply reduced enrollments) at 49th and Chestnut streets. The West Philly Speedboys still play their home football games on what is now called Pollock Field.[14]

Author’s Note on Primary Sources

Primary sources for this article include U.S. Bureau of the Census, decennial censuses 1910–1940; Philadelphia birth and death certificates and City marriage indexes; City property maps available online in the Free Library of Philadelphia’s Print and Picture Collection; Philadelphia Tribune, articles accessed through ProQuest Historical Newspapers, and leading African American newspapers indexed by Digital Public Library of America; historic photos in the George D. McDowell Philadelphia Evening Bulletin Collection, Temple University Special Collections Research Center.

[1] Neil Lanctot, Negro League Baseball: The Rise and Ruin of a Black Institution (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004), 1–5.

[3] Ibid., quote from p. 19; see also Rebecca T. Alpert, “Harry Passon: Philadelphia Baseball Entrepreneur,” Society for American Baseball Research (SABR), The National Pastime, 2013, accessed from http://sabr.org/research/harry-passon-philadelphia-baseball-entrepreneur.

[4] George W. Bromley and Walter S. Bromley, “Atlas of the City of Philadelphia, wards 24, 27, 34, 40, 44 & 46, West Philadelphia, from actual surveys and official plans,” published by G.W. Bromley, Philadelphia, 1927, plate 24.

[5] Biographical sketch, Eli K. Price Papers, University of Delaware Library, Special Collections Dept.; see also Elizabeth M. Geffen, “Industrial Development and Social Crisis, 1841–1851, in Philadelphia: A 300-Year History, ed. Russell F. Weigley (New York: Norton, 1982), 359, 360.

[8] Alpert, “Harry Passon”; Lanctot, Negro League Baseball, 27, 29.

[9] Lanctot, Negro League Baseball, 29–33; quote from p. 33.

[10] Lanctot, Negro League Baseball, 35–37.

[12] “Negro League Baseball,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negro_league_baseball.

[14] “West Philadelphia High School,” accessed from https://wphs.philasd.org/about-us/, 14 May 2019.