Mantua Against Drugs

Part of

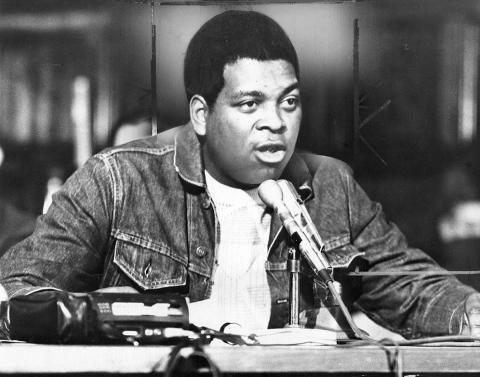

Herman Wrice, who founded Mantua Against Drugs (MAD), led a brave 15-year campaign to drive narcotics dealers from Mantua and to shut down their crack houses.

During the era of the crack epidemic—the mid-1980s to the Millennium—community activists rose up in poor African American neighborhoods to drive out narcotics dealers and shut down crack houses. One such community organizer was Herman Wrice, founder of Mantua Against Drugs (MAD), who, with the help of like-minded activists, mobilized anti-drug marches and protests to thwart the dealers. The “Wrice Process” attracted national attention, and the Department of Justice enlisted him to help towns and small cities organize to effectively deal with the crack phenomenon.

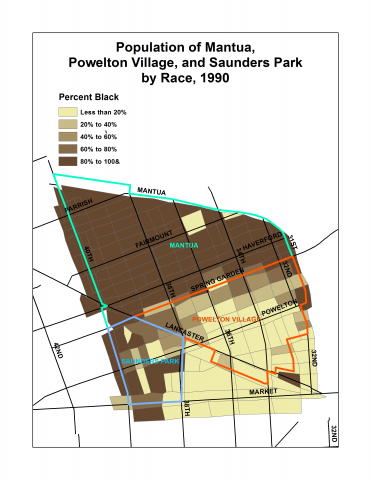

Throughout the crack era—the mid-1980s to the Millennium—grass-roots organizers in poor African American neighborhoods worked bravely and stalwartly, often under the radar of national media, to suppress the drug culture and the violence it spawned in their neighborhoods. Mantua was home to transformative community leaders of this ilk who formed neighborhood groups such as the Young Great Society, founded by Herman Wrice and Andrew Jenkins; Mantua Community Planners, founded by Jenkins; Mantua Infant Care Center, founded by Jean Wrice, Herman’s wife; and Mantua Against Drugs, founded by Herman. These groups worked locally to take back the neighborhoods and streets from the drug dealers and rival gangs. We focus here on Herman Wrice, Philadelphia’s most famous anti-drug activist and one of the nation’s most recognizable anti-drug crusaders.

Herman Wrice was born in West Virginia in 1939. He moved to Philadelphia with his mother seven years later. Wrice’s youthful experience of street life would provide an indispensable trove of street knowledge for what became his life’s work: keeping youth out of gangs, off drugs, and off the streets. These experiences made Wrice a relevant and approachable figure, an authentic “old head,” for the conduct of his work with neighborhood teens who were often ensnared in gangs.

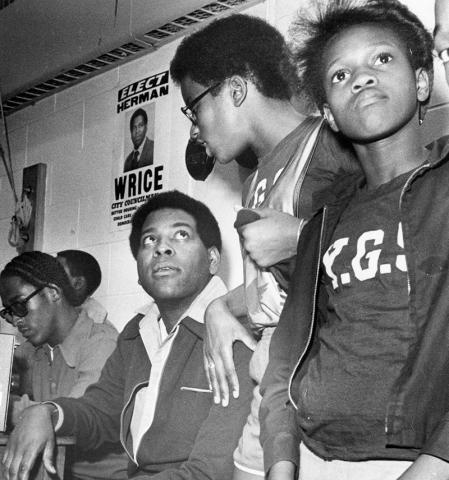

Wrice and Andrew Jenkins founded the Young Great Society in 1965 after the two men’s wives were nearly killed in a crossfire between rival gangs while the two women were shopping at a store at 36th Street and Fairmount Avenue. Both families, as well as the rest of the men who helped found the Young Greats, lived in Mantua Hall, a large Philadelphia Housing Authority building at 3500 Fairmount Avenue.

Wrice and Jenkins first attempted to reason with senior gang members. However, they soon realized these men were “too seasoned” to be coaxed away from the gangs. Jenkins says, “So what we had to do was begin to work with a younger generation, so we decided to work with the peewees, and they are around 13, 14 years old, rather than hold conversations with them at 17, 18, 19 and 21. So that’s how we began the Young Great Society.”[1]

The Young Great Society, officially underway and thriving by 1966, was effective in engaging youth to be their better selves and providing these young people opportunities for self-improvement. The Society’s activities included three different summer school programs for more than 500 youths; YGS football teams; track events for youth at the University of Pennsylvania; and, for the wider community, a “hospital on wheels,” a mobile treatment center parked at the corner of 39th and Olive Streets. Whenever “rumors of rumbles” circulated in the neighborhood, Young Great Society members would take to the streets “in their blazer jackets” to act “as a steadying force.”[2] The Young Great Society worked to create a safe space for neighborhood kids to be kids. For example, young people were given the resources and rooms to stage plays about the things that concerned them, and what concerned them most was Mantua’s gangs.

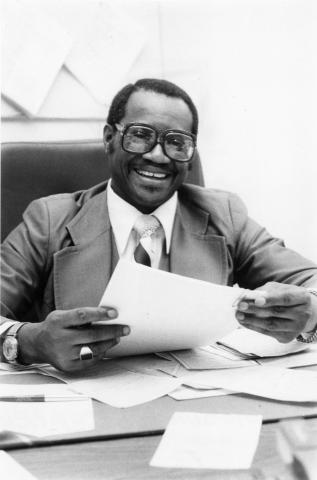

After the success of the Young Great Society and a failed bid for a City Council seat, Wrice moved to Iowa, where he lived from 1977–1985 and worked to rehabilitate drug addicts. He returned to Mantua in 1986 at the onset of the crack epidemic, moving into a house on Spring Garden Street. In 1987, a year that saw twelve murders in Mantua, Wrice founded Mantua Against Drugs (MAD). While MAD espoused many of the same principles as the Young Great Society, Wrice gave his new organization a more specific and urgent purpose: to take back the neighborhood from violent crack dealers and shut down all drug trafficking in Mantua. To advance this mission, Wrice and his MAD allies sealed off at least twelve abandoned buildings that could be used as crack houses by bricking up the windows and doors; cleared areas of trash and debris that could be used to hide drugs or guns; and, at great personal risk, confronted dealers face to face. Wrice “often faced death threats; he was not only fearless, he once taunted the drug dealers to come get him while he worked cleaning a street corner park. They didn’t.”[3]

MAD was known for its wanted posters showcasing “the dealer of the week.” Symbolizing their intent to demolish crack houses and shooting galleries and build or renovate structures for constructive community uses, Wrice and MAD demonstrators carried bullhorns and wore white construction helmets as they marched by night to suspected crack houses—“All armies need uniforms,” said Wrice. They mounted vigils at these sites and confronted both sellers and buyers. Wrice wore “a laminated badge [issued by the police department] designating him a Drug March coordinator: “The badge is a symbol of the wary but increasingly respectful bond that has grown between Wrice and Philadelphia police.

Working side-by-side with the community, Wrice’s homegrown tactics helped neighborhood residents to reconnect with one another and feel more in control of the drug dealing and the violence that was taking place in the streets. This method— especially the tactic of targeting neighborhood drug dealers—gained traction, both with community groups throughout the city who came to believe Wrice’s message of “Stand up to them and they’ll leave,”[4] and with media and politicians who began to see the utility of Wrice and his uncompromising grass-roots approach. Grass-roots organizing Herman Wrice-style featured Wrice “holding court” with community petitioners at his cramped, once fire-bombed office on North 35th Street and hosting weekly community meetings at the nearby Grace Lutheran Church at 36th Street and Haverford Avenue. Wrice offered help to groups to expel local crack dealers on two conditions: they asked for MAD’s help and they agreed to organize themselves as an anti-drug campaign. When these terms were met, Wrice dispatched his new troops to the suspected crack house. A parallel strategy was to confirm delinquent utilities bills on the house and pressure each utility agency to disconnect its service to the house; enlist a city code enforcer to request rent receipts from the dealers, which were often not forthcoming; and, in the latter case, evict the dealers and their junkies as squatters of a public nuisance. Sometimes the threat of city confiscation of a suspected crack house or the money being lost on delinquent rents from dealer-renters sufficed to get the legal owner (if he or she could be found) to cooperate with MAD.[5]

With the nation in the throes of the crack epidemic, what was known as the “Wrice Process” offered a rare ray of hope to drug-stressed communities. His strategy was acclaimed by an array of politicians, including Philadelphia Mayor Wilson Goode, who gave Wrice his trademark white hard hat; Pennsylvania Governor Robert P. Casey; Senators John Heinz and Arlen Specter ; and President George H.W. Bush, who hailed Wrice as the “John Wayne of Philadelphia.”[6] In the early 1990s, Wrice joined a movement of black leaders calling for “tough on crime” city policing, notwithstanding the tendency of big-city police departments to act with a heavy hand in poor black neighborhoods. In his 2017 book Locking Up Our Own, James Forman Jr., a Columbia University professor and civil rights attorney, documents the hardening views of Washington DC black officials over a forty-year period as they confronted escalating violence related to drugs. Their views evolved into a hardline stand on black crime and drug use. they supported unforgiving anti-drug laws, vigorous law enforcement, and stiff sentencing guidelines that failed to distinguish non-violent from violent drug offenders. In Philadelphia Herman Wrice aligned his organization with the 1991 mayoral candidacy of Republican Frank Rizzo, a former police commissioner and mayor, who was seen by many of Philadelphia’s 334,000 blacks as a white racist (in Rizzo’s 1987 campaign against the black Democrat Wilson Goode, he received only 2.6 percent of the black vote). Rizzo appealed to Wrice and other Against Drugs leaders in the city on the strength of his record as a relentless enforcer of law and order. Wrice also found an ally in the hardline anti-drug commentator Tucker Carlson, who touted Wrice and MAD.[7]

Herman Wrice and Mantua Against Drugs worked to stem the tide of devastation and violence from crack cocaine through committed and focused pressure on the supply side of the drug trade. The process empowered the residents to reclaim and reassert their claim over the neighborhood. Wrice’s critics pointed out that drug dealers ousted from one neighborhood could easily set up shop in another. “Where do they go?” Wrice responded. “I don’t know where they go. I’m not in the ‘where-they-go’ business. I’m in the ‘send-you’ business.” The “send-you” business was dangerous. Wrice knew the dealers wanted him off the streets. Though he was the likely target of an assassination attempt, he refused to back down to the dealers. “Let the undertaker take the hat off,” he told CBS News.[8]

Herman Wrice died of a heart attack in Florida on 10 March 2000. From the early 1990s, he had been an emissary of the Department of Justice, visiting cities and towns, advising citizens and police departments on MAD’s strategy against drugs. Wrice’s process infused anti-drug activism in some three-hundred communities nationwide, from heartland cities such as Cincinnati and Fort Wayne to towns such as Taylor, Texas and Marion, Indiana. At the time of his death, he was planning an anti-drug march in Fort Lauderdale.[9] C.B. Kimmins, a teacher and native of Wynnefield who had joined MAD in its early days, assumed Wrice’s mantle as the organization’s director.

How effective was Wrice’s anti-drug campaign in Mantua? That’s difficult to say with any statistical precision. For the four-year period between 1989 and 1993, “the number of serious crimes reported in Mantua declined at more than twice the rate of that in Philadelphia overall, and it is not likely that demographic changes [for example, murdered drug dealers and ones forced by rival gangs from the neighborhood] alone can explain such a precipitous drop in serious crimes, not when it takes place over only four years. Criminals in Mantua didn’t just stop committing as many crimes. Something, or somebody, made them stop.” That was the conclusion reached by the Department of Justice when it hired Wrice to head out to the hinterlands with his process.

Perhaps Wrice’s legacy is best captured in a famous quote by the anthropologist Margaret Mead: “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it's the only thing that ever has.”[10]

[1] “A Lifetime of Service: A Conversation with Rev. Dr. Andrew Jenkins.” Audio recording accessed from http://funeralforahome.org/story/andys-chest/, 4 January 2019.

[2] “Take It to the Streets: The War on Drugs: A Philadelphia Model,” accessed from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2m1cxMTy_GU, 4 January 2019.

[3] "Herman Wrice: Co-Chairman of the Philadelphia Urban Coalition," Philadelphia Tribune, 9 May 1970.

[4] “Powelton Village Profiles,” accessed from http://www.poweltonvillage.org/profiles/herman_wrice.html, Spring 2017; no longer online.

[5] Tucker Carlson, “Smoking Them Out,” Policy Review 71 (Winter 1995), https://search.proquest.com/docview. Today an ultra-conservative television commentator and fellow of the Heritage Foundation, Carlson was a staunch advocate of Wrice and his national campaign against drug dealers in the 1990s. Carlson’s article provides a trove of useful information on Wrice and his career. For exceptional film footage of the Wrice-led vigils and the Wrice Process, see “Take It to the Streets.”

[7] Forman Jr., Locking Up Our Own; “Rizzo Anti-Drug Stand Garners Black Support,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 18 June 1991; Carlson, “Smoking Them Out.”

[9] Ibid.; Carlson, “Smoking Them Out”; Acel Wright, “Herman Wrice Took the Bottom to the Heights of Social Renewal,” commentary, Philadelphia Inquirer, 16 March 2000.

[10] Quoted in Michele Alexander, “None of Us Deserve Citizenship,” commentary, New York Times, 23 December 2018.