MOVE on Osage Avenue

Part of

On May 13, 1985, after three years of nuisance complaints from MOVE’s Osage Avenue neighbors, a confrontation between MOVE and the Philadelphia Police ended in arguably the most traumatizing event in Philadelphia’s history.

In 1982, some of the MOVE members who had escaped incarceration following the 1978 shootout with Philadelphia police in Powelton Village, settled into a rowhouse at 6221 Osage Avenue, where they broadcasted demands to the city through a loudspeaker day and night. Complaints voiced by neighborhood residents were tabled at City Hall, even as MOVE members constructed an armed barricade on the roof of the house. Under mounting pressure to act, Mayor Wilson Goode authorized a tactical plan to evict MOVE. On May 13, 1985, the eviction process went awry, resulting in a day-long gun battle between MOVE and city police. In the early evening, a satchel bomb dropped from a police helicopter onto the barricade ignited a fire that the fire department failed to control. The fire caused the deaths of 11 of 13 MOVE members (six adults and five children), destroyed two city blocks of middle-class homes, and left an indelible stain on the city’s reputation (“The city that bombed itself”).

In 1982, MOVE members of all ages settled into a row house at 6221 Osage Avenue on the western fringe of West Philadelphia, just a block from Cobbs Creek Park. The house was owned by former MOVE member Louise James, sister to MOVE founder John Africa (aka Vincent Leaphart). In late 1983—as city officials turned deaf ears to the organization’s continued demands for the release of their incarcerated brethren—MOVE members began to broadcast these demands day and night through a loudspeaker at the Osage Avenue site. This activity outraged their largely middle-class African American neighbors, whose complaints were heard but tabled by high-level city officials, including Mayor W. Wilson Goode, Philadelphia’s first African American mayor, who took office in 1984. The Goode administration was terrified by the prospect of another violent confrontation with MOVE. Yet the stage was already being set for the terrible violence that erupted at 6221 Osage on May 13, 1985.

MOVE styled itself as a “self-defense” organization even as it mounted an aggressive campaign on the 6200 block of Osage to demand the release of the incarcerated MOVE 9. Ironically, members’ actions—incessant profanity-laced diatribes shouted day and night over the loudspeaker system and threatening behaviors on the street —had a direct impact only on MOVE’s neighbors on or around the 6200 block. These residents vigorously voiced their complaints on multiple occasions to City Hall and the police—to no avail.

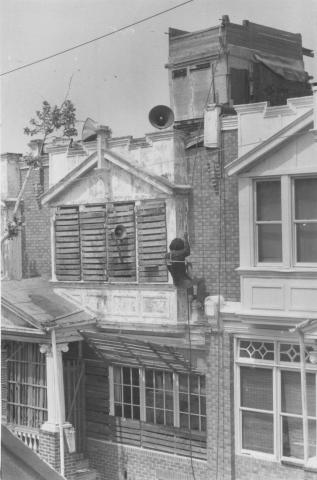

The last straw for MOVE’s neighbors was the erection of a fortified “heavy timber” bunker on the roof of 6221 Osage, with “holes that were gun ports.” On April 30, 1985, the neighbors, at wit’s end, appealed to Governor Richard Thornburgh in a high-profile news conference.

We are here to let the governor know about the disquietude and general state of terror we are forced to live under by the MOVE organization. We want the governor to know that regardless of whatever may have happened in the past, today MOVE is a clear and present danger to the health and safety of our entire block. We also want the governor to know that we have been to our elected representatives in city and state government, but to date nothing of any consequence has been done. We are now asking Governor Thornburgh to step in and deal with this situation.

Finally spurred by the appeal to the governor, Mayor Goode requested a tactical plan for removing the occupants of 6221 Osage. The city’s district attorney, Ed Rendell (a future Philadelphia mayor and Pennsylvania governor) activated outstanding arrest warrants for four adults in the house, and the police had a court order to remove the children (ages 7–13), who were illegally kept from attending school—this part of the plan called for taking the children into custody during their daily outing in Cobbs Creek Park. What the plan didn’t call for was the intercession of local mediators who knew MOVE, the neighborhood, and the situation on the 6200 block.

Late on the night of May 12, Mother’s Day, police evacuated the block and the houses on surrounding streets. Most of the 500 police officers on the scene took vantage points in nearby houses that afforded views of the front of 6221 Osage; a tactical team guarded the rear alleyway, which MOVE had barricaded at its property lines, and two teams were positioned to lay siege to 6221 through the walls of adjacent row houses.

At 6 a.m. the following morning, Police Commissioner Gregore Sambor yelled through a bullhorn, “Attention, MOVE! This is America! You have to abide by the laws of the United States!” After reading the arrest warrants, he announced, “We do not wish to harm anyone. All occupants have fifteen minutes to peacefully evacuate the premises and surrender. This is your only notice. The fifteen minutes starts now.”

MOVE did not stand down. That morning a sustained gun battle broke out, and the police were outfitted with M16 semi-automatic rifles, Uzis, shotguns, 30.06 and .22-250 sharpshooter rifles, a Browning automatic rifle, and a Thompson submachine gun. In the words of the Philadelphia Special Investigation Commission, which investigated the events of May 13, the police fired “over 10,000 rounds of ammunition in under 90 minutes at a row house containing children.” High-pressure water hoses and tear gas canisters were also employed.

MOVE’s resistance lasted into the late afternoon. As nothing else was working, Mayor Goode, who was not present at the scene at any time during the day or evening, authorized the release of a two-pound satchel bomb, composed of Tovex and C-4 explosives, from a state police helicopter onto the fortified bunker on top of 6221. According to the MOVE Commission, “The fire which destroyed the Osage neighborhood was caused by a bomb which exploded on the roof of the MOVE house. The fire began milliseconds after the bomb blast when friction-heated metal fragments penetrated a gas can on the roof and ignited gasoline vapors.”

One disastrous decision begat another. Firefighters were on scene throughout the day but took no immediate action. Police Commissioner Sambor and Fire Commissioner William C. Richmond had decided to let the fire burn as a tactical weapon to force the occupants from the house. Unfortunately, their communications were badly garbled, and the fire burned for more than an hour before the firefighters turned on their hoses. By this time, 6:32 p.m., the fire was out of control. Conventional fire-fighting failed, and by dawn the next morning, the 6200 block of Osage was obliterated. Sixty-one houses lay in smoldering ruins and 11 MOVE members (six adults and five children) lay dead in the rubble. Among the dead was John Africa, MOVE’s founder, who had not been present at the 1978 shootout in Powelton Village and who had lived at other MOVE sites outside Philadelphia in the intervening years. In the gutted house, the police found only two pistols, two shotguns, and a 22-caliber rifle—hardly a match for the military-style assault mounted by the police.

Two MOVE members managed to escape the inferno—Ramona Africa (née Ramona Johnson), an adult, and Birdie Africa, age 13, both of whom were badly burned. Whether the MOVE members who remained in the house were pinned down by gunfire and unable to get out remains an open question—and an open wound—in the still-lingering controversy about the events of May 13, 1985.[1]