Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander

Sadie Alexander broke barriers of race and gender as the first African American woman to achieve many accomplishments, and she worked diligently to open opportunities for others to follow in her footsteps.

Dr. Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander was a path-blazing Philadelphian who broke numerous precedents by obtaining a B.A., a Ph.D., and a J.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. She faced significant racial and gender discrimination during her educational career. She was the first African American woman to practice law in the state of Pennsylvania. During her life both her education and her experiences with discrimination led her to work with multiple organizations fighting for equal rights.

Childhood

“If I would tell you my medical history, you would agree with me that I was destined to live for some years”[1]

Sadie Tanner Mossell was born on January 2, 1889 in a house at 2908 Diamond Street, Philadelphia, which was owned by Sadie’s uncle, the artist Henry Osawa Tanner.[2] Sadie’s mother, Mary Louisa Tanner, had an excruciating time with her pregnancy––she had suffered several previous miscarriages, and this time she was dragged half a block while trying to put her other children on the Ridge Avenue Trolley.[3] Happily, Sadie arrived at full term; her mother would later remark that her daughter was “destined to come into the world.”[4] Bishop Benjamin Tucker Tanner, Sadie’s grandfather on her mother’s side, baptized her with water from the River Jordan, and she was named Sadie Tanner Mossell, after her maternal grandmother.[5]

When Sadie Mossell was a year old, her parents separated.[6] Sadie would later recall that the separation brought shame to her mother, who lost her status as the wife of a graduate of Lincoln University and the first African American to graduate from the University of Pennsylvania Law School.[7] The abandonment by Aaron Albert Mossell led to an abrupt change in the family’s lifestyle.[8]

When Sadie reached school age, her mother sent Sadie’s older siblings to live with their uncle, Louis Baxter Moore. Moore was the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from the University of Pennsylvania. After his graduate work, he served as the Dean of Education at Howard University in Washington, D.C.[9] Sadie made numerous trips back and forth between Washington, D.C. and Philadelphia––travel that disrupted her schooling; she never finished a full term during her elementary and middle school years, though apparently with no ill effects.[10] Once she was of high school age, her mother left her in Washington, D.C. to complete her education.

While in Washington, Sadie attended the legendary all-Black M Street High School. Later in life, she recounted that the students at M Street were “constantly exposed to talks by graduates” who were “living examples of what was possible if we applied our ability.”[11] There, the students attended lectures by Booker T. Washington, Mary Church Terrell, Coleridge Taylor, and W.E.B. Du Bois. Being in the presence of such influential African Americans, she wrote, helped students study “Negro history from living exhibits–not history books.”[12]

Because she lived with her uncle, Sadie was able to frequent the campus of Howard University. She would recall the time when Booker T. Washington spoke at her uncle’s house.

Now Howard played a big part in my life. They used to have speakers from all over the world come to Howard University, and I remember distinctly Booker T. Washington coming…I do recall that they planned a reception for Mr. Washington, and that he first said…how he regretted that he couldn’t stay for the reception. And he jokingly said that “people who came to Washington and breathe the air of Washington overnight seemed to never [be] able to leave”[13]

Sadie’s exposure to Washington’s words must have stuck with her, for when she graduated from M Street High School (now Dunbar High School), she was fully prepared to attend Howard University: “I sewed all summer, getting ready to be the best-dressed girl on the campus.”[14] However, Sadie’s mother insisted she return to Philadelphia and attend the University of Pennsylvania. In her distress, Sadie pitched a tantrum to try to get her mother to change her mind:

I jumped up and down on the bed trying the break the springs. I cried and she just let me alone. Well, in my day, you didn’t do what you wanted to do. You didn’t do your own thing. You did the thing your parents told you to do. So on to the University of Pennsylvania I went.[15]

As Sadie prepared to leave Washington, she received encouragement not only from the faculty at M Street High School, but also from faculty and administrators at Howard University.[16] As she would later say, her teachers “put in us a determination that nobody would beat us.”[17] It was this encouragement that brought her to Penn with the attitude: “I could and I would.”[18]

Undergraduate Studies: Freshman and Sophomore Years

“When I entered Penn’s School of Education in September 1915, I was convinced I had the ability to succeed.”[19]

In September 1915, Sadie Tanner Mossell started her freshman year at the University of Pennsylvania seeking a degree in education. At this time, many of the female undergraduates had previously attended normal schools (teaching training schools).[20] Sadie’s first semester at Penn was particularly challenging; besides the usual adjustments to college life freshmen had to make, she had to confront blatant racial discrimination.[21]

Sadie’s negative experiences with her White classmates on campus caused her to question her ability. She recalled these moments painfully when she described her first year at Penn:

Not one woman spoke to me in class or when I passed one or more than one woman on the walks to College hall or the Library. Can you imagine looking for classrooms and asking persons the way, only to find the same unresponsive person you asked for directions seated in the classroom, which you entered late because you could not find your way? Let us imagine you came from outer space and entered the University of Pennsylvania School of Education. You spoke perfect English, but no one spoke to you. Such circumstances made a student either a dropout or a survivor so strong that she could not be overcome, regardless of the indignities.”[22]

Sadie not only experienced racism from her classmates, but also from faculty and staff at Penn.[23] For example, she would recall that she was often unable to check out library books; she was often brushed aside when she asked for help in locating a book or was curtly told by the librarian, “It is out.”[24] Sadie also found that she was unable to get a hot meal, either on campus or in the immediate neighborhood—an injustice she had to endure until she attended Penn’s Law School.[25] No lunch counter in the University area served Black students. “We don’t serve Colored people” was a common refrain; sometimes the N-word was used in Sadie’s presence.[26]

The second semester of Sadie’s freshman year was more encouraging. She began to make friends in what she described as “the first thaw in the ice that covered my freshman year.”[27] During the spring semester, the School of Education invited its students to a tea for which each student was expected to bring sandwiches. Sadie’s elation at being invited turned to “great despair” when she learned, by scrutinizing a list for the event, that her contribution was expected to be a “bottle of olives;” someone had scratched out the word “sandwiches” beside her name.[28] Undaunted, Sadie did not bring a bottle of olives to the tea, but rather “sandwiches of such beauty you cannot destroy.” Sadie’s homemade sandwiches were such a success with her classmates that in the coming years they would press her to provide the sandwiches for events; she would accede to such requests only for “an individual or organization I felt deserving.”[29]

Sadie excelled academically.[30] From the outset, she saw her undergraduate work as preparation for a graduate program.[31] This is not to say that the faculty with whom she discussed her goals took her seriously. Their skepticism did not deter Sadie, whose only response was, “Time will tell.”[32] At the end of her freshman year, she could congratulate herself on the self-control she had learned by fending off countless racist “remarks on and off campus.”[33] She finished her first year on a strong academic note: an average G+, with G standing or “good.” Sadie, however, was disappointed with her grades and vowed that in the coming year, she would achieve the grade of Distinguished, the “highest grade according to the method of marking at that time.”[34]

Concerned with the health of her elderly grandfather and her dependence on him for her $175 tuition, Sadie decided to complete her degree in three years. She started her sophomore year the following summer, and thus lessened the financial burden on her family.[35]

Sadie would recall her sophomore year as “more pleasant and satisfying than I could possibly have imagined.”[36] She continued to make friends and to excel in her academic work. Sadie’s sophomore year marked the beginning of her crusade for civil rights. As mentioned earlier, African American students were not allowed to eat at neighborhood lunch counters and many of these students, Sadie included, had to depend on sack lunches brought from home.[37] Encouraged to speak up on this matter, Sadie showed her tenacity by scheduling a meeting with Edgar Fahs Smith, provost of the University of Pennsylvania, and importuned him “to use the influence of his office to declare eating places that refused any Penn student off bounds for Penn students.”[38] She also asked that the University provide a venue for not only African American students, but also for poor students where they could get a hot meal for lunch.[39] Although she was turned down, her actions bespoke a civil rights activist in the making.

Sadie also fought against the “second-class” position of the women attending the University of Pennsylvania.[40] The women, she contended, were “serious about their studies,” yet many courses at the University were open only to men.[41] Interested in economics and insurance, Sadie Alexander and her classmate Mary Stewart decided to sit in on a class at the Wharton School. Unfortunately, when the professor entered the class, he immediately announced that he did not teach women and ordered Sadie and Mary to leave.[42] Though discouraged, Sadie was more determined than ever to achieve her goal of a Ph.D. degree.[43]

Undergraduate Studies: Junior and Senior Years

“I wasn’t thinking about marrying Raymond or anybody else because I had things on my mind that I wanted to do.”[44]

The following September, Sadie entered the second semester of her junior year and became friends with Raymond Pace Alexander—a freshman at the Wharton School of Finance and Commerce.[45] Their friendship was the highlight of her final year as an undergraduate. She would defer her marriage to Raymond until she completed her Ph.D. studies.

Sadie remained determined “to secure an outstanding record and a solid education so that when I entered public life, I would have the background to assume responsibility and leadership.”[46] Fixated on her studies, she continued to ignore the “pettiness of my classmates who did not speak to me.”[47] Sadie registered for ten courses and received Distinguished in all of them. Though she was not awarded a Phi Beta Kappa key, an honor she deserved, Sadie received a graduate scholarship, and the dean of education gave her a tiny broom for “‘making a clean sweep of D’s.”[48]

Ph.D. in Economics

The first year of graduate school, Sadie Mossell applied for one of the few fellowships offered to women at the University of Pennsylvania–the Harrison Fellowship. She had the support of the department for the fellowship. Henry Miner Patterson, head of the Economics Department, assisted Sadie with her application.[49] Unfortunately, mistaken identity and racial insensitivity prevented her from receiving the award. She vividly described this moment:

I knew what day they were meeting. When the meeting was over, I was still in the library waiting to hear. And Dr. Patterson told me to come over to his office. When I got over there he asked me what had I done to the books of a graduate student who was in the library. I told him I had never touched anybody’s books. So he said Dr. Jastro, the librarian, had got up and made a speech against me and said that under no circumstance should I have it [the fellowship] because I had disturbed all these books of a student who was just at the point of comparing citations…“Well,” Dr. Patterson said, ‘I will go back, but it’s too late…they’ve already awarded it to someone else.”[50]

Eventually, the department realized that Jastro had mistaken Sadie for another Black student. “I was sick,” she later recalled, “but they stood behind me the following year.”[51] In 1919, she won the Francis Sergeant Pepper Fellowship and received her Master of Arts degree in Economics.[52]

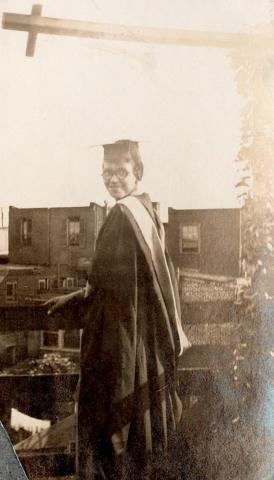

In June of 1921 at the age of 32, Sadie Mossell was awarded her Ph.D. in Economics and became the first African American woman in the United States to receive that degree in economics. Her dissertation was titled, “The Standard of Living Among One Hundred Negro Migrants Families in Philadelphia, 1921.”[53]

Another important achievement of this period of her life was Sadie’s induction into the Gamma Chapter of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc. This was the third chapter of the organization and the first Black sorority on the Penn campus.[54] Furthermore, at the astonishing age of 30, Sadie Mossell was elected to become the first National President of Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.[55] Describing it as one of her most “rewarding experiences,” [56] she led this international service organization created for the betterment of the African American race.

Upon completing her doctoral degree, Sadie struggled to find employment in the field of economics.[57] She applied to numerous insurance companies in the Philadelphia area, but they were not hiring African Americans. Finally, she was hired as an assistant actuary by the Black-owned Mutual Life Insurance Company in Durham, North Carolina.[58] The next two years were burdensome for her as she battled loneliness and experienced prejudice from southern Blacks because she was from the North.[59] Nevertheless, Sadie filled her spare time writing Raymond Alexander, and she returned to Philadelphia in 1923. On November 29, Sadie Tanner Mossell and Raymond Pace Alexander married at the Tanner family home on Diamond Street.[60]

During her first year of marriage, Sadie Alexander remained in Philadelphia while Raymond Pace Alexander completed his law degree at Harvard University.[61] During this time she realized her ambition to obtain a similar degree for herself and applied to the School of Law at the University of Pennsylvania.[62]

Law School

“I went to law school and I enjoyed law school. However, I was met with many obstacles, but I was strong enough then not to let them worry me. And I also realized that on the campus…I had become really a pet.”[63]

In 1924, Sadie Alexander was the first Black woman to enroll in the School of Law at Penn. She made the Law Review her first year, becoming the first Black woman to achieve this distinction at the University.[64] Despite her accolades, Alexander still experienced incidents of racism on campus. Notably, the Dean of the Law School, Dean Michael, ignored her in the hallway; moreover, he forbade other women students from inviting Alexander to join their clubs, and he asked that she not be appointed to the Law Review.[65] Nevertheless, Sadie Alexander had the support of classmates and other faculty to assist her in securing this well-deserved honor.[66]

Life after Penn

“Our interest in better race relations had naturally come as a result of our experiences and our desire to see that this doesn’t continue to happen.”[67]

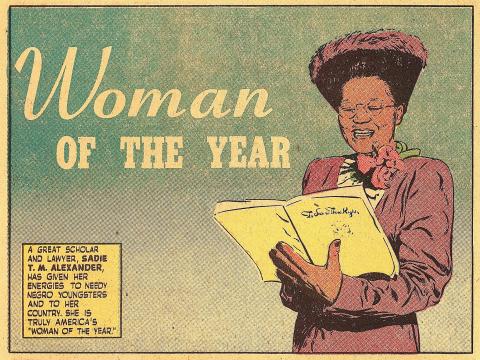

In 1927, Sadie Alexander became the first African American woman to practice law in the state of Pennsylvania. She managed a private law firm with her husband until 1959, when she opened her own law firm and her husband became a judge for the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas.[68]

In addition to her legal career, Sadie was an active member of the Parent and Teacher Association (PTA), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), the National Urban League, and other service organizations.[69]

An important cause for Sadie and her husband was the quest for better race relations in Philadelphia. Their interest stemmed from the challenges they experienced as African Americans in a racially divided city. One event in particular––involving a local Philadelphia theater––spurred Sadie to work in civil rights and family law.[70]

While hosting a friend from Cornell University and wanting to attend a play at the Shubert Theatre, Sadie asked Raymond if he would arrange a blind date to escort her guest. Raymond Alexander agreed and asked his classmate to accompany the Cornell student and go to the Shubert to purchase the tickets for the play. Because Raymond’s classmate could pass for White, the theatre released the tickets without issue.[71] However, when the Alexanders and their friends arrived at the theatre that evening, they had a jarring experience:

When we got to the theater, they told us there was some mistake. These tickets were no good and where did we find them? So we were quite persistent and each one of us started to speak what little foreign language we were able to handle and it was quite amusing…the manager didn’t know what we were speaking and he finally said, “They’re not niggers.” And then he offered us a box and we pretended that we didn’t want a box.”[72]

In 1970, Henry J. Abraham, President of Phi Beta Kappa, Delta Chapter, oversaw the induction of Sadie Alexander and her husband into the prestigious society—a long overdue honor. Overcome with gratitude, Sadie Alexander wrote to Abraham to say that the Phi Beta Kappa induction was “the second happiest day of my life,” with her happiest day being the day she received her Ph.D. and being “interviewed and photographed by the news media from all over the world.”[73]

In November 1989, Dr. Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander died of complications from pneumonia and Alzheimer’s Disease. As the news of her death spread, hundreds of media outlets nationwide paid homage to her. One eulogist, Claude Lewis, lauded her as “proof that people can overcome any obstacle, so long as they don’t suffer from the worse kind of poverty of all, poverty of the spirit…I will miss her always.”[74]

Alexander’s Legacy at the University of Pennsylvania

“Work hard and prepare perfectly for every case and devote yourself to further causes which advance improvement of all phases of the human condition and spirit.”[75]

Sadie Alexander is memorialized today in the name of one of Philadelphia’s K–8 public schools, the Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander Partnership School (informally called the Penn Alexander School).[76] Proposed in 1998 and opened in September 2001, the Penn Alexander school provides children in its attendance zone “with research based instruction and holds them to high academic standards.”[77] Serving 600 children, this public school is overseen by a partnership governing board that represents the School District of the Philadelphia, the University of Pennsylvania, and the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers.[78] It is richly provisioned with state-of-the-art classrooms, an atrium that serves as a performance space, and a wetlands for nature studies, among other avant-garde facilities. To ensure small classes and a flow of ample resources, Penn provides a stipend of $1,000 per student per year above the School District of Philadelphia’s average per-pupil expenditure.[79] The school’s location at 4209 Spruce Street affords convenient access for its pupils to a wealth of academic and cultural resources, notably, the University City Arts League, the Penn Museum, the Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts, the Institute of Contemporary Art, the University Archives, and the Walnut Street West branch of the Free Public Library.[80]