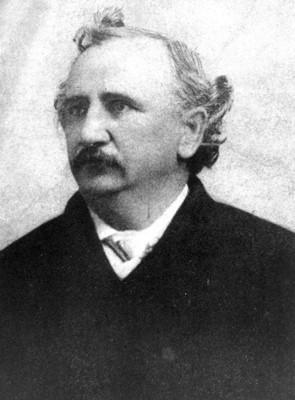

Thomas E. Miller

Thomas E. Miller was notable as a member of the South Carolina legislature and senate during the Reconstruction era; later, at the onset of the Jim Crow era, he served a short-term in the U.S. House of Representatives; he and his family arrived in Powelton in or around 1921.

Thomas E. Miller bravely forged a political career as a black state legislator and state senator in South Carolina during the turbulent decades that followed the Civil War. He also served briefly in the U.S. House of Representatives. In his later life, Miller resided for about a decade with his wife and two other family members in a house the couple owned in Powelton.

Early Life and Formative Years

Thomas Ezekiel Miller was born in South Carolina in 1849. It is likely that three of his grandparents were white. He was adopted at birth by Richard Miller, a freed slave. He was light enough to have “passed as white” in the North, but he chose to live most of his adult life as a person of color in his native state. When he died in 1938, his obituary in the Journal of Negro History described him as “one of the most useful men of his time.”

When he was a child, the Millers moved to Sumter, S.C. and sent him to a school for free blacks. His mother died when he was nine years old and he had to work as a newspaper boy to support himself. The end of the Civil War found him in New York State. The story of his journey north has been summarized in many confusing ways. The clearest version appears in an interview with him during the 1930s. He explained that

“[he] was placed in charge of delivering the paper to all stations between Charleston and Savannah, Ga. on the Savannah Railroad and remained in service until 1864, when he was made Assistant Conductor of the railroad. He wore the Confederate uniform, for all public works were owned and operated by the federal [i.e., Confederate] government. In the early part of 1865, the train was captured by the Yankees to the South of Harleyville [South Carolina] and he was placed into prison in the stockade river swamp, at Savannah Georgia, and remained there for two weeks. The few persons [who] survived were moved to the Savannah Hospital, where he also went. When he was released from the hospital, he went to Hilton Head en route to Harts Island, N.Y. with the N.Y. 24th Negro Regiment, and from there to Hudson, N.Y. and returned to Charleston in 1866.”

Legal Studies and South Carolina Racial Politics

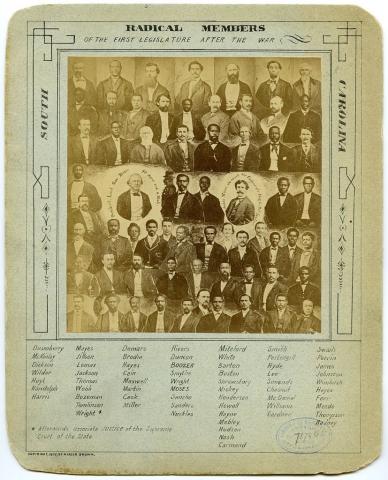

Before returning to Charleston, Miller studied for nine months at a school in Hudson. He soon returned north to study at Lincoln University, where he graduated in 1872. After again returning to South Carolina, he was appointed School Commissioner in Beaufort County. (This was the era of Radical Republican Reconstruction and Northern military control of the former Confederate states, when some 700 blacks were elected to Southern legislatures.) Miller’s first important political victory was to get black teachers into the Charleston city schools. He was elected to the state House of Representatives in 1874, 1876, and 1878, and to the state Senate in 1880.

While serving in the legislature, Miller studied at the Law School of the State University, graduating with the last class before blacks were barred from that institution (the white ‘Redeemer’ era in South Carolina marked the end of Reconstruction). He also received legal training under P.L. Wiggins, the state solicitor and Franklin J. Moses, Sr., Chief Justice of the South Carolina Supreme Court. He was admitted to the bar in 1879.

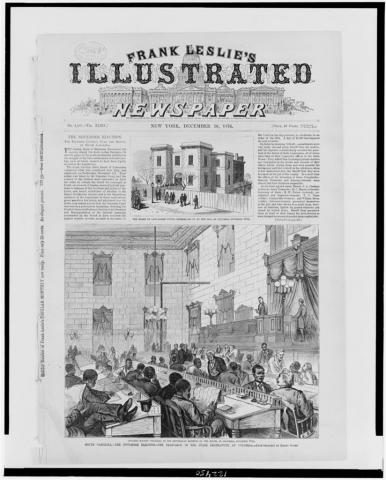

In 1888, Miller ran for the U.S. House. The election was disputed but he was finally seated by the Republican Congress in September 1890. He only served for a few weeks before he had to return home to campaign for reelection. Another contested election followed, but this time a Democratic Congress refused to hear his case. In 1895, he was elected to the South Carolina Constitutional Convention along with only five other blacks. Putting a legal stamp on Jim Crowism in South Carolina, the Constitutional Convention approved poll taxes and literacy tests, which effectively barred black males from voting.

During the Redeemer and Jim Crow eras, the black population of South Carolina desperately needed leaders with Miller’s legal training and rhetorical skills who would fight for their rights. Miller was constantly reminded of his light complexion; the white press referred to him derisively as ‘Canary Bird’ Miller. And some black opponents accused him of acting in his own self-interest during Reconstruction. Regardless, Miller remained undaunted in his advocacy for black rights and in his outspoken criticism of white supremacists’ terrorist tactics. Miller was the best educated of the black delegates at the Constitutional Convention of 1895—in this case, to no avail. The valiant defense of black rights made Miller and his allies failed to halt the disfranchisement of South Carolina blacks.

At the 1895 Constitutional Convention, Miller eloquently challenged the notion that blacks were an alien group intent on dominating the state. He reviewed the common history shared by blacks and whites, defended actions of black legislators during Reconstruction, and pointed out that many white legislators relied on black votes for their election. He did not, however, hesitate to speak harsh truths, even at one point bravely challenging the “Lost Cause” view of the Civil War, asserting:

“The majority of you blame the poor Negro for the humility inflicted upon you during that conflict, but he had nothing to do with it. It was your love of power and your supreme arrogance that brought it upon yourselves. You are too feeble to settle up with the government for that grudge. This hatred has been centered on the Negro and he is the innocent sufferer of your spleen.”

Miller was a strong advocate of universal suffrage. He noted the effects a poll tax would have on poor whites, and he was one of a small minority at the convention to vote for women’s suffrage.

A Black College Presidency in a Jim Crow State

After the Constitutional Convention, Miller turned to education as a sphere for black advancement outside politics. In exchange for promising to leave politics, he secured the separation of the Colored Normal, Industrial, Agricultural and Mechanical College of South Carolina (now the State College of South Carolina) from Methodist-owned Clafin College. He demanded that “only Southern men or women of the Negro race be on the faculty.” He was appointed the College’s president by the all-white Board of Trustees. The College was poorly funded and for a decade lacked running water, sewers, electricity, and central heat. During its early decades, State College wasn’t really a college; most of its students were in primary or secondary grades. That the white Board of Trustees tightly controlled the curriculum explains the prominence given Booker T. Washington’s (Tuskegee Institute) model of industrial education in the College’s course of study, which offered teachers licenses and basic training in agriculture, including how to care for cows and make a compost heap. (The College didn’t grant a real bachelor’s degree until 1925). At all events, Miller served as president until 1911, when he was forced to resign following his outspoken opposition to the election of Governor Coleman Blaise. Miller’s opposition to Blaise wasn’t surprising given Baise’s aversion to the education of blacks. For example, Blaise once stated that efforts to educate blacks were detrimental because “you are ruining a good plow hand and making a half-trained fool.” After resigning, Miller resumed his law practice and looked after other business interests.

Private Life and Move to Powelton

Thomas Miller and Anna Hume were married in Charleston, South Carolina in 1874. They had nine children, two of whom died young. In or around 1921, Thomas and Anna moved from South Carolina to 3405 Hamilton Street in Powelton; Thomas was now about 71 years old and Anna was about 66. Sources disagree as to the year of the move, with most dating it as 1923. Yet they purchased the house in 1921, and an article in the Philadelphia Tribune on 1 March 1924 stated tellingly: “Ex-Congressman Miller is a celebrated character in Philadelphia, where he was worked for a number of years . . .”

Accompanying Thomas and Anna to 3405 Hamilton Street were their daughter Pansy and her husband, Dr. Charles W. Maxwell. A 1904 graduate of the Howard University Medical School, Charles treated patients in and out of 3405 Hamilton, and he maintained an office at 616 South 15th Street. His father, Henry Johnson Maxwell, had served in the Reconstruction-era South Carolina state legislature alongside Thomas E. Miller.

When the Millers arrived in Powelton, the neighborhood had only a small black population. The first black homeowner in Powelton may have been Bessie G. Johnson, wife of Fields Johnson, who purchased 320 N. 31st St. in 1919. In 1920, excepting the Johnsons, the black residents on 31st and 32nd Street were renters. By 1930, most residents east of 33rd Street were black renters. West of 33rd Street, Powelton was racially white, excepting a few black servants in white households and Summer and Winter streets, where by 1940 all the residents were black.

Why did Anna and Thomas Miller choose to leave South Carolina for Philadelphia? And why did they choose Powelton rather than an established black neighborhood such as the Maxwells would later choose? We may never know. The Maxwells may have initiated the move to Philadelphia. Also, Philadelphia—and particularly Powelton—may have offered a quiet retirement removed from the harshness of life in South Carolina after World War I. Thomas Miller wrote several manuscripts based on his experiences in South Carolina politics—ones he may have written during his years in Powelton. (It appears, however, that they were never published.)

Final Years in Charleston

In the early 1930s, the Millers returned to Charleston, where Anna died in 1936. The house in Powelton was inherited jointly by Pansy Maxwell (who had no children) and the five children of Pansy’s sister, Marguerite E. Edwards of Atlantic City, New Jersey. Pansy and Charles Maxwell left 3405 Hamilton in the late 1930s to live on South 15th Street, in an established black neighborhood. Charles remained a prominent physician in the black community until his death in 1959.

Thomas Miller died in Charleston in 1938. The inscription on his tombstone reads: “I served God and all the people, loving the white man not less, but the Negro needed me most.” (Some sources differ on the exact quote.)

I have not found a real biography of Thomas Miller nor a full appreciation of his role in South Carolina history. The numerous short biographical sketches include many inconsistencies and inaccuracies that are now easily correctable with readily available sources. Here are several of the sources I used for this piece:

Augustus Ladson, Ex-Congressman Thomas Ezekiel Miller, WPA Federal Writers’ Project on African American Life in South Carolina, 1936–1937, WPA_K_1_1_065070, Charleston County, University of South Carolina.

“Recalls Stirring Incidents in Life of Thomas E. Miller, Veteran of Reconstruction Days,” Philadelphia Tribune, 10 October 1935.

“Thomas E. Miller,” Journal of Negro History 23, no. 3 (1938): 400–402.

George B. Tindall, “The Question of Race in the South Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1895,” Journal of Negro History 37, no. 3 (1952): 277–303.