The West Philadelphia Community Free School

The West Philadelphia Community Free School—an experimental school annex created to alleviate overcrowding at West Philadelphia High School—was ultimately undone by conflicting visions for how it would function.

In May 1969 community residents held a sit-in at a University of Pennsylvania school building to protest the overcrowded conditions at West Philadelphia High School (WPHS). Negotiations between the University, the community, and WPHS resulted in an experimental solution—the West Philadelphia Community Free School (the Free School). The annex was a variation of a European model focusing on flexible, community-based education. From the outset, tension created by conflicting visions for the school highlighted issues surrounding the inability of the Free School to address the needs of the community. At the root of this conflict was an attempt to answer the question of –whose school was it? The Free School’s first director, Aase Eriksen, and the teachers wanted to propel forward the vision of a “free” school—one that would unleash students’ potential and engage in an alternative mode of schooling. In contrast, the Community Board, particularly the Board’s representative Novella Williams, felt that this form of education would undermine the students’ ability to participate in a broader society. In the end, the pervasive internal conflicts circumvented any progress in fulfilling meaningful and significant changes for the community.

Background

In May 1969, West Philadelphia activist Novella Williams, president of a grass-roots organization, Citizens for Progress, and her associates staged a sit-in at the University of Pennsylvania’s Dietrich Hall, home of the Wharton School. They had come to the Penn campus to protest overcrowded conditions at West Philadelphia High School—an institution that was 99 percent African American, with some 3,800 students packed into a building whose capacity was 2,400.

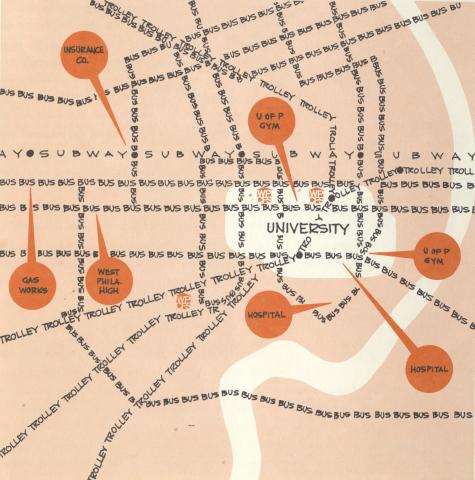

The Penn campus was a logical location for the sit-in because of the University’s recent role in the creation of the University City Science Center, which displaced more than 2,000 Black residents along the Market Street corridor between 34th and 38th streets. To relieve the overcrowding, Williams’s group called for rooms in Dietrich Hall for the community to use as classrooms. They “wanted to make a point” that the University owed the community some compensation for its “encroachment” in West Philadelphia.[1]

The University refused to acquiesce in this demand. “They didn’t respond as we had hoped,” Williams remarked. “We hoped they would give us space for 1,200 students on the campus. They lacked the initiative to really come through with a secondary education on the campus. That would really have been a landmark.”[2] Even so, Penn administrators felt considerable pressure to do something to appease these vocal activists. The sit-in opened the door for negotiations in which the University agreed to support an annex to West Philadelphia High School that would be a marked improvement over the education students typically received in the high school’s main building at 47th and Walnut streets.

Planning the West Philadelphia Free School

The free school concept of the West Philadelphia Community Free School emerged from the sit-in negotiations. Nationally, the free school concept “represented a growing political movement to return ‘power to the people.’”[3] Free schools were designed to be relatively autonomous, minimally bureaucratic, radically experimental high schools that tailored curricula in culturally appropriate ways to serve the developmental needs of their students.[4] They were to be the antithesis of traditional teacher- and textbook-centered education. In the aspects of community control and curricula, free schools were part of the late 1960s and 1970s national zeitgeist of educational experimentation, which included open education programs and community-centered schools, among other types, and new curricular approaches such as cultural journalism and real-world internships.[5]

In the summer of 1969, a tenuous partnership was created involving the leaders of the three groups that would develop the Free School: the School District of Philadelphia, the Community Board of the West Philadelphia Community Free School, and the University of Pennsylvania.

Each of these groups brought their own agendas to the partnership. Representing the School District, WPHS Principal Walter Scott wanted to alleviate overcrowding in the high school and to avoid any racial controversy in doing so. The previous spring, students at the high school had mounted a disruptive month-long strike against George Fishman, an allegedly incompetent, allegedly racist history teacher—an action that recalled the involvement of WPHS students in the notorious November 1967 riot at School District headquarters, which, by most accounts, was instigated by Philadelphia police apparently acting on orders from Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo.[6]

The Community Board had more on its plate than relieving the overcrowding at WPHS. Not liking what they saw at the present high school—perennially low scores on standardized tests and student apathy coupled with an alienating, impersonal environment—the Community Board, whose representative was Novella Williams, wanted a “new kind of school” that would inspire young people to aspire to a college degree and give them the tools to achieve that goal. Significantly, Williams and the Board’s other Black members wanted “community control” of the Free School’s policies.

The third partner, the University of Pennsylvania, represented by Francis M. Betts III, from the president’s office, and Aase Eriksen, of the Graduate School of Education (Penn GSE), aimed to reduce the tension that existed between the University and West Philadelphia’s majority-Black neighborhoods; Eriksen was to be the linchpin of the University’s involvement in the Free School. In summer of 1970, the three parties formally agreed to the establishment of an annex to the main WPHS building that would provide “an innovative and experimental educational program designed for this community.”[7]

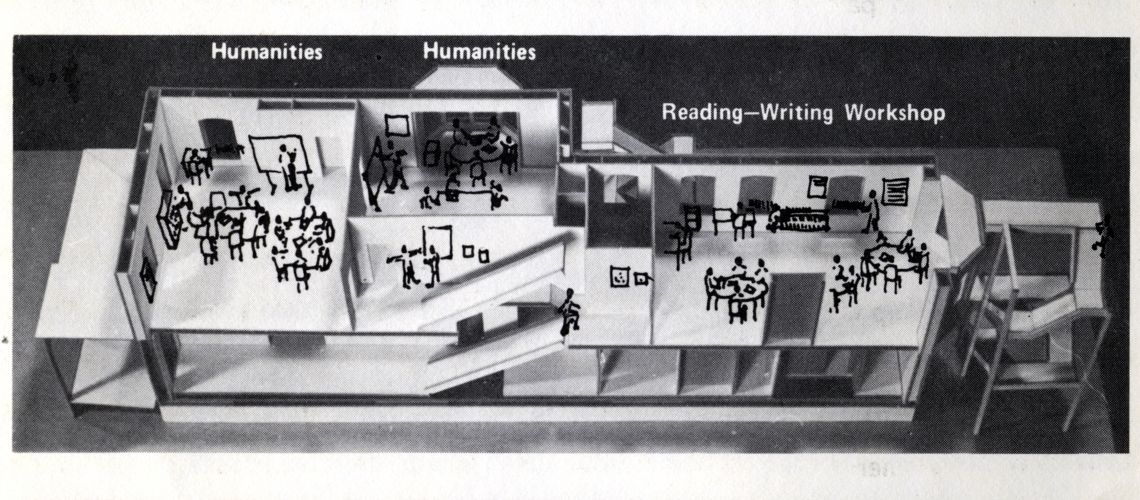

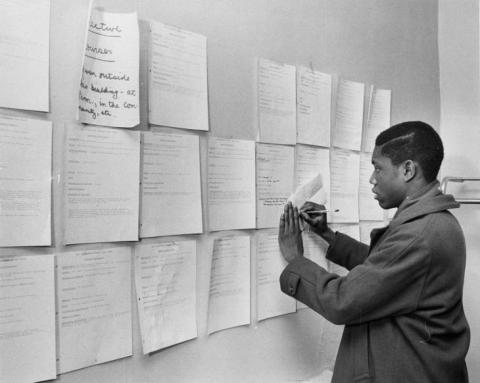

West Philadelphia’s version of the free school concept drew largely from Eriksen’s work on “scattered school sites.” A dynamic instructor at Penn GSE, Eriksen was inspired by the Danish model of free schools, or friskolar, which were independent, state-funded Danish schools “designed to give parents and students a choice in public education.” Eriksen’s concept was a loose translation of this model. She advocated organizing “houses” of no more than 200 students—in effect small high schools—that would be spread around the neighborhood to provide a “free” and developmentally appropriate, “open learning” curriculum. The houses were to be non-graded (in other words, no 10th, 11th, or 12th grade). The Free School would offer curricular choices and autonomy to students who had spent years in the regimented classrooms of overcrowded buildings.

For the curriculum, each house would offer a “basic program” that included developmentally appropriate intellectual activities and content in literature, social studies, math, and foreign languages. A salient component of the curriculum was the “outside courses”—student internships in businesses, institutions, and agencies around the city, with options ranging from “violin instruction to astronomy with a Penn professor, to anesthesiology taught by a staff member at Children’s Hospital, to clerical training at local banks.” The “family group” was another important feature of Eriksen’s plan. Each teacher would have responsibility for 12 to 15 students, provide a family-like home base for each student, and create “a cohesive group structure for interpersonal relations to grow.” Free time for students was another component. Regarding the latter, Eriksen said, “Travel time to outside courses as well as some free time will be built into the rosters to give the students time periods in the school week over which they have control.”[8]

Having agreed upon an innovative program that seemingly aligned with everyone’s interests, the triumvirate of Scott, Williams, and Betts/Eriksen agreed that Eriksen would be the first director of the Free School and would also serve as an educational consultant to help develop the curriculum. Her appointment set the stage for the Free School’s implementation. The University reportedly agreed to cover the salaries for Eriksen and her support staff, and to provide an additional donation of $60,000.[9]

As events proved, Eriksen’s model ran athwart of Williams’s expectation of community control of the Free School. As Elaine Simon, a former Free School teacher, put it: “The initial idea, the concept of the scattered site school and some of the international notions about how it would be structured were definitely not the ideas of the people in the community.” From the very beginning, there were “different conceptions of what the Free School would be,” though the problem “did not manifest itself initially.”[10]

Trouble from the Outset: Agendas in Collision

Though the West Philadelphia Free School was intended to be a collaboration between the new school’s majority-Black Community Board, the University, and the School District, it was riven by tensions from the outset. A clear divide emerged between the teaching staff and Board members regarding the mission of the Free School, as well as its organization.

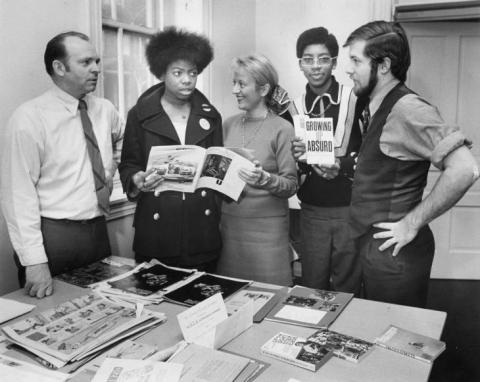

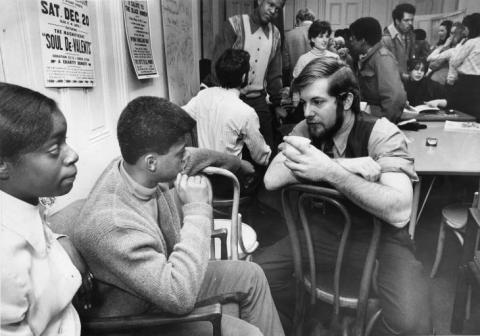

The primary source of teachers for the Free School was Penn GSE’s Experimental Program in Urban Education, a master’s degree program that immersed teachers-in-training—from the time of their arrival at Penn to their graduation—in the life and schools of West Philadelphia. Many of these students were graduates of Ivy League colleges. “Twenty-two of us came to Philadelphia the summer of 1969, and we lived all together in a house over in the Mantua community,” Jolley Christman, a former Free School teacher, recalled in an interview 20 years later. “That summer we [worked] with the Young Great Society, which was a Black community organization involved in housing, daycare, [and] a number of community revitalization projects.” Following a semester of coursework in the fall of 1969, Christman and her colleagues in the Penn GSE program were expected to work as part-time interns in the local schools. Aase Eriksen recruited Christman and six other Penn GSE interns to teach at the Free School.[11] All seven interns were White. Staffing the Free School mainly with White teachers and interns eventually became a point of concern with the Board.

Officially, the Free School was designated an annex of WPHS—a single school that operated in separate houses. The Free School opened in February 1970 as one house with eight certified teachers (from WPHS), seven teacher interns from Penn GSE (contrary to the University’s program guidelines, they were full-time teachers), and about 225 WPHS students. The student recruitment process worked as follows: Names were randomly drawn from the entire student population at WPHS. The lottery winners were invited to attend the Free School. If a student declined to enroll, another name was drawn until the quota was filled.[12]

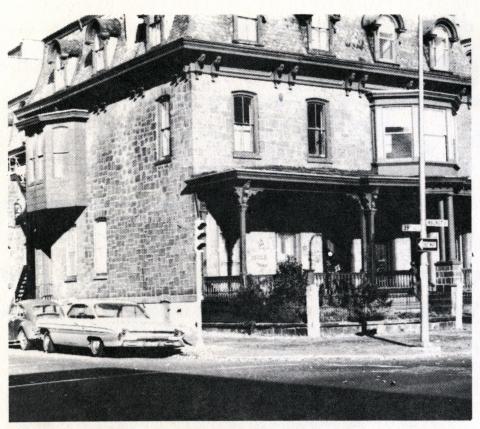

From the very beginning, the physical structure of the Free School proved overly complicated. Until a suitable building, one close to the University, could be located and renovated to meet health and safety requirements, the school was forced to operate in a fragmented fashion with virtually no resources. For the first month of operation, Free School teachers and students huddled in the spare rooms of several buildings in the University area: St. Mary’s Episcopal Church, at 40th and Locust streets; the Free Library, at 40th and Walnut streets; and the headquarters building of the University City Science Center, at 36th and Market streets.

In March 1970, a three-story building at 3625 Walnut Street, which the University leased from the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, was ready for the school. For the remainder of the spring semester, the teachers, now in one building, focused on their “family groups,” teaching concepts, and general principles by means of teacher-guided projects; they worked in teams and emphasized the interdisciplinarity nature of the subject matter. Some 20 organizations offered outside courses.[13]

By summer’s end in 1970, the school comprised three houses: House One, at 3833 Walnut Street; House Two, at 3625 Walnut; House Three, at 4226 Baltimore Avenue. To teach some 450 students, a total of 32 full-time teachers, including 12 new interns from Penn GSE’s Experimental Urban Teacher Training Program, were appointed—28 Whites and 4 African Americans; 20 of the teachers were certified. The teachers were apportioned across the three houses by subject area, with two teachers appointed as co-heads for each house. The staff was “remarkably young (three-quarters of them were in their early twenties).”[14]

The Free School’s first full year was 1970–71. The House Two building stood in the Walnut Street business district across the street from the Penn campus. The block included two Penn-student dives called Pagano’s Pizzeria and Grand’s Restaurant, and a bowling alley. It was here that tensions first surfaced between the Community Board and Eriksen and her teachers. The trouble had started the previous spring, when Board members complained about students’ “free time.” Writing in 1972, Eriksen appeared to acknowledge the legitimacy of the Board’s complaint: “It became apparent that students were using their free time for seemingly aimless activity: for hanging around, playing cards, making noise, and bothering local merchants…[which] led to a problem of cutting classes: students tended to extend their free time periods into their class periods, either arriving late for classes or not attending at all.”[15]

The free-time issue was part of a larger negative impression that Novella Williams and her associates began to form in regards to education innovation, one that would mark the first several years of the school’s operation. “We feel we know our people and our kids,” Williams bluntly told the Young Great Society Foundation. “And the fact is, you can’t do the same things with Black kids that you do with White. You can’t give them as much freedom. One of the problems is that a blond, blue-eyed teacher usually can’t discipline Black kids. They’re afraid to, they’ve got guilt hang-ups, they want to be ‘buddies.’ These students don’t need more friends, they have too many already; what they need are adults who care about them enough to teach them something.”[16] Arthur Hyde, who taught at and studied the Free School in its early years, put it this way: “The Board’s main program concern was with excesses of student behavior as indicative of young White teachers’ inability to discipline Black kids.”[17]

Their original enthusiasm for Eriksen’s model notwithstanding, the Board members now chafed at the free-time abuses and complained about Eriksen’s inattention to administrative details, which Eriksen apparently regarded as intrusive bureaucracy. In November 1970, the Board, which included the School District administrator singularly responsible for the Free School—Principal Walter Scott—appointed one of Scott’s vice principals, Ola Taylor, to replace Eriksen as director, and bring administrative order to the Free School. Taylor represented a shift back to traditional schooling. She brought with her an “old school” mentality and a regimented style of management. And she was unlikely to challenge Scott’s strategy of using the Free School to outsource the main building’s problem students. After November, Eriksen continued in her role as an educational consultant for curriculum development, and the teachers continued to look to her for guidance until she left the project in the summer of 1971. Taylor, who was less experienced in instructional leadership, largely left the 32 teachers to their own devices. Most of them stayed true to Eriksen’s philosophy.[18]

House Two and Its Discontents

During the Free School’s first year, the program at House Two epitomized the innovative curriculum, giving the students choice and flexibility. The academic program offered “inside courses” in biology, algebra, general science, Spanish and German, humanities (combined English and social studies—an “experimental interdisciplinary” approach), and a reading and writing workshop for all students. House Two students could attend physics, chemistry, and French courses offered at the other houses. Students chose courses they needed as credits toward graduation.

House Two students spent two to six hours a week in “outside courses”—a total of 70 were provided by businesses, industries, and organizations in West Philadelphia and Center City. An “outside course coordinator” recruited the providers and oversaw the courses—a sizeable undertaking. The University opened its gyms (Gimbel for swimming, Hutchinson for calisthenics) and Franklin Field for weekly physical education classes, although the students did not feel welcomed by Penn staff members.[19]

Fire and water damage in June 1971 made it impossible for House Two to use 3625 Walnut Street in the following academic year. In the 1971–72 school year, the house’s relocation to 35th Street and Lancaster Avenue proved fateful. The first problem was the dismal condition of the building and its unsuitability for the Free School:

“The building selected by the administrators for House Two was a real source of concern to the teachers. Although cleaned and partially repaired, it was old and dilapidated [it was built as a schoolhouse in the 1850s]; crumbling and falling plaster was a constant menace; the lavatories were dank and frequently unworkable; rodents were never exterminated. The physical structure was institutional and reinforcing of the fact that it was a school and not a ‘house’ as in the previous year.”[20]

The second problem with the Lancaster Avenue location was youth gangs. Random lottery as the means of student selection to the Free School was designed to randomly distribute any gang members who won a seat at the school across the three houses; in theory, no house would have more than one or two members of a given gang. The theory, of course, assumed that the selections would be random. That was manifestly not the case. Writes Arthur Hyde, “In 1971–72, when House Two moved into the Mantua-Powelton area, of the new students that came to the house, 47 percent were from that area. At this time only 19 percent of the new students coming to House Three were from Mantua-Powelton.” Mantua-Powelton was the home turf of the 36th and Market Street Gang, and members of that gang were a disruptive presence at House Two. [21]

Information provided by three former teachers and a former Board member interviewed in 1989 corroborate Hyde’s finding that in the second full year of the project, Walter Scott used the Free School to divest the main building of its major behavioral problems—the cast-offs were gang members and other WPHS students with records of poor behavior. Quite simply, notable troublemakers at WPHS surfaced at the Free School in ways that defied the logic of a random sample. For example: “We had Chewy and Cool Earl,” Elaine Simon, a former Free School teacher, recounted in 1989. “The biggest graffiti artists in the city…These guys took pride in having their names everywhere. In the weirdest places, too. That’s too coincidental…too unlikely to have happened by chance.”[22]

House Two was the locus of the Free School’s gang problem. In the early weeks of the 1971 fall semester, 36th and Market Street Gang members roamed in and out of the building. The teachers voted to allow non-disruptive visiting “outsiders” to attend classes. Ola Taylor, the director, was not pleased. According to one of Arthur Hyde’s informants, “The director…came in screaming and yelling at the kids to leave, which really sent out a bunch of mixed signals to our kids. Like, who is in charge? Are the teachers able to strike a bargain with the kids or are they going to be overruled? Are they a bunch of weak-kneed people who can’t stand up?” No serious disruption occurred until mid-October, when gang members “trashed” a teacher’s room and smashed a piano, an action that prompted the teachers to summon the police for the first time.[23]

By the early winter months, gang warfare was a real possibility. Egged on by the 36th and Market Street Gang, two rival gangs—June Street and Hoope Street—were primed for a conflict, and teachers feared that House Two would be the battleground. (Two former June Street members left the Free School after receiving death threats.) The breaking point for teachers was an incident in front of the House: a non-gang member “was severely beaten…by Hoope Street members, when a Market Street member purposely falsely identified him as being from June Street.” Putting themselves at risk for gang retaliation, the teachers called on the police to clear the street. Then they petitioned Ola Taylor to remove the three most disruptive gang members. The director complied with their request and sent a non-teaching assistant to stand guard at the front entrance of the building.[24]

None of this turmoil endeared the teachers of House Two to Novella Williams. When the antiquated building incurred water damage in the spring of 1972, the teachers requested a temporary space for the house on the Penn campus. Frank Betts agreed, but Williams said no. “She did not want the problems of House Two’s students (gang members) to be on display before the White community of the university,” says Hyde. “She felt that the teachers could not ‘control’ the students on the roll, let alone the outsiders who might visit. Thus, the predominant image of House Two in her mind was the familiar notion of White teachers allowing Black kids too much freedom.”[25]

Withdrawal of the University

Following Aase Eriksen’s departure, the connection between the University and the Free School weakened. Penn had neither the will nor the money to continue its support. In the 1960s, the University had spent freely on its campus expansion projects—new buildings and major renovations—to the extent that it piled up sizable deficits in its operating budget. In jeopardy, according to Gaylord P. Harnwell, Penn’s president from 1953–1970, were “the maintenance of the quality of teaching and research programs, as well as the capability of extending adequate financial aid to students.” Harnwell attributed Penn’s fiscal crisis to “the combination of inflation, economic recession, declining revenues, government cut-backs, and in some instances, a decline of philanthropic contributions.” Under Harnwell’s successor, Martin Meyerson (1970–1981), the University would continue to operate with significant budget deficits until 1976.[26]

Summarily stated: Its affairs consumed by budgetary woes, safety and security issues (violent crime was on the upswing in West Philadelphia), and campus race, gender, and labor turmoil, the University turned away from the West Philadelphia community in the 1970s. Penn’s relationship with the Free School was an early casualty of its institutional retreat from West Philadelphia. As Hyde tersely puts it, “In the summer of 1971, the University of Pennsylvania ceased active involvement in the Free School; Dr. Eriksen, teaching interns, and monies no longer were available.”[27]

The Free School in Decline

As the water damage in House Two turned out not to be serious, the teachers chose to remain in the building until the summer of 1971. By this time, however, House Two’s future was a moot point. Walter Scott, Ola Taylor, and the Community Board decided to close House Two and to open the Free School in the fall as only two houses—House One and House Three—with a total of 350 students. (Jolley Christman, a teacher and a survivor of the consolidation, would teach at House One at 3833 Walnut Street until she left the Free School in 1974.)

Ola Taylor returned to WPHS in June 1973, and her position at the Free School was filled by a male teacher from the main building. A second consolidation, 1974–75, reduced the Free School to a single house—House Three on Baltimore Avenue—with only seven teachers and 150 students. Her aims unrealized, Williams’s presence in the Free School diminished—she moved on to other causes. Hyde calls the remnant program “modified traditionalism”—the turmoil was gone, but so was the excitement. The last years of the Free School were years of decline. Unfortunately, no available source confirms the closing date of the annex—it was either 1977 or 1978.[28]

Free School: Irreconcilable Perspectives

Three agendas were in conflict during the short-lived heyday of the Free School, the years 1970–1972. These agendas were represented by WPHS Principal Walter Scott, Novella Williams and the Community Board, and the Free School teachers from the University.

- Walter Scott saw the Free School as a means both to reduce overcrowding at WPHS and to outsource the main building’s disruptive students, especially its gang members. What role did the Free School play in relieving overcrowding? In 1971–1972, WPHS enrolled approximately 2,800 students, compared to 3,800 in 1969–1970. Four-hundred and fifty Free School students in 1971–72 account for about half this reduction (other reasons for the declining enrollments are not clear). In short, WPHS was no longer overcrowded (the Free School helped with that) and the Free School was helping to clear the main building of its worst behavioral problems. Once Aase Eriksen was out of the picture—she was likely privy to Scott’s strategy—and Ola Taylor was on site to manage paperwork minutiae and keep the central office happy, Scott had no reason to involve himself any further in the operation of the Free School; according to Hyde, he made only one visit to House Two in 1971–72.[29]

- The Community Board, which often deferred to Novella Williams, had a long-term agenda that conflicted with the aims that governed teacher practice at the Free School; these aims were embedded in Eriksen’s model. In the Free School’s first full year of operation, Williams and her associates were dismayed by the very practices they had ostensibly agreed to in the joint proposal of August 1970, which Williams had co-authored with Scott and Eriksen. The practice of the free-wheeling Free School violated her idea of what a “real school” should be. In her view “the lack of discipline by teachers” and shoddy administrative and accounting procedures were symptomatic of well-intentioned though misguided White liberalism. Says Hyde, “[The Community Board] felt that while the Whites may feel free to take ‘educational risks’ through experimentation in the short-run, the Black community and its children would have to live with the eventual consequences, not the Whites, who could move on.”[30]

The Community Board, which was “basically middle-class,” had a “fairly traditional concept” of the Free School and wanted “an elite school, college preparatory, for West Philadelphia kids.”[31] Yet the Board’s aim outstripped the Free School’s capacity to achieve it. Specifically, the Board’s concept could not be reconciled with the reality of an alternative school that functioned as an annex to an underperforming high school and was dependent on that institution as its only source of high-achieving students. Arthur Hyde insightfully captured this irreconcilability of aim and capacity as follows:

Implied in the rhetoric of the [Eriksen model] and the actions of the White innovators was the school was to ‘turn on’ those who had been disenchanted with traditional education…That the Free School would have a disproportionately low number of students of high previous success would not have been troublesome if the Black community members of the board had seen the school as one which was to ’turn on’ such disenchanted students. However, they held a different value and a different purpose for the school. They wanted the school to provide academic educational experiences for preparing students for colleges and subsequent professional careers… Yet the group of students who, as a whole, would be most likely to have or to accept such values were those who had achieved some success in their previous schooling. This group would be the one least likely to come to the school with its alternative, experimental, innovative premises.[32]

3. The Free School teachers were single-mindedly dedicated to the students who showed up on their doorsteps. Most of these students were, as Hyde put it, “disenchanted.” The Free SchooI teachers engaged these alienated youths as individuals. “I don’t want to label kids too much,” said Jolley Christman, “but the Free School and its structure was successful with kids who came with low skills, who had been on the fringes, who had been marginal at West Philadelphia High School, who had not attended classes, who were very poor readers, had poor basic skills, who had just basically…opted out of school and become anonymous at West Philadelphia High School.”

The teachers identified the Free School as their school. Imbued with the idealism that marked many other college graduates of their generation, they were politicized and committed to social justice. “We met constantly,” Christman recalled, “I never got home before seven o’clock at night (the school day ended at 2:30 p.m.). I ate, slept, and breathed this school. These other teachers, I will never feel about people like I felt about them. We worked so hard. We worked every weekend. We met at night. I can’t tell you how many times I slept over at other teachers’ houses just because it was too late to go home…It was a mission. [repeats] It was a mission.”[33]

Final Note

The West Philadelphia Community Free School prefigured an early concept of charter schools—the concept advanced by Ray Budde in the mid-1970s and given serious attention by urban teacher activists a decade later, with the endorsement of Albert Shanker, president of the American Federation of Teachers. With Budde, Shanker endorsed “a procedure that would enable teams of teachers and others to submit and implement proposals to set up their own autonomous public schools within their schools [sic] buildings.” Budde’s concept envisioned charters as teacher-owned, -operated, and -controlled hothouses for experimental approaches to urban education.[34]

Paying no attention to lessons that might have been learned from the experience of the West Philadelphia Free School, the School District of Philadelphia, in the late 1980s, embarked on a “schools within schools” campaign—first, under Superintendent Constance Clayton, from 1989–1992, with the city’s comprehensive high schools divided, by fiat, into “charters” whose teachers lacked any real autonomy; next, under Superintendent David Hornbeck, from 1994– 2000, with every high school broken into “small learning communities” (SLCs, irreverently known as “Slicks”); finally with Superintendent Paul Vallas, from 2002–2007, with the emergence of charter schools as “schools of choice” in an education marketplace of “diverse providers.” Significantly, none of this activity meaningfully improved the overall performance of the School District. And Ray Budde’s idea of experimental, urban education hothouses whose curricula are designed and controlled by teachers—an idea roughly approximated in the West Philadelphia Free School—did not inspirit Philadelphia school reform.

Novella Williams was “a West Philadelphia civic leader who began her fight against crime and corruption in her own neighborhood and pressed her advocacy for human rights and affirmative action onto the national stage.” She was the founder and president of Citizens for Progress, a non-profit that she headed for five decades. The West Philadelphia Free School was one of her many causes. “Novella S. Williams, 87, Civic Leader” Philadelphia Inquirer, obituary, 15 March 2015.