“Board of Buzzards”: Medical Grave Robbing in Nineteenth Century West Philadelphia

For its dissecting tables, the University of Pennsylvania Medical School purchased cadavers stolen from the grounds of the Blockley Almshouse.

Although grave robbing occurred near medical schools across the United States in the nineteenth century, as a consequence of its place as a prestigious seat of American medicine, Philadelphia’s grave-robbing racket was internationally notorious. The Philadelphia Almshouse’s large potter’s field was among the city’s most targeted sites for grave robbing and was a major source of bodies for dissection at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School.

“The traditions of the Almshouse are revived; and the feeling of indignation and horror which prevailed in the community about ten years ago, at the discovery that the dead bodies of the paupers had been sold as merchandise to medical and surgical colleges, for anatomical purposes, is still fresh in the minds of people.”1

Body snatchers, grave robbers, ghouls, buzzards, resurrectionists: all these titles refer to those paid to venture into burial grounds and steal freshly buried bodies for anatomists. Until the passage of the 1883 Anatomy Act in Pennsylvania, which effectively ended the practice, the difference between the demand for cadavers in medical schools and the availability of corpses of criminals and suicides to legally dissect meant that many Americans feared that their bodies would be furtively taken from recently filled plots and carted to a nearby anatomical hall.2 Public protest against this practice in Philadelphia traces to at least 1765, when William Shippen, the first professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school, was the target of one of the first public protests against grave robbing in the United States.3 Poor and Black Philadelphians were acutely aware of the risks of burial in an unguarded cemetery. Stories of resurrectionists even became fodder for dark nursery tales in the City of Brotherly Love.4 Although body snatching occurred near medical schools across the United States, as consequence of its place as a prestigious seat of American medicine, Philadelphia’s grave-robbing racket was internationally notorious in the nineteenth century.5

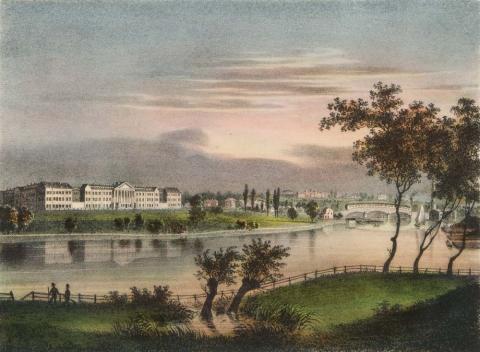

For its dissecting tables, the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school acquired cadavers stolen from the grounds of the Blockley Almshouse. This is the context: Prior to 1835, the Philadelphia City Almshouse was located at 11th and Spruce streets, near Penn’s second campus, at 9th and Market Streets. In 1832, the Philadelphia Hospital, also known as the Blockley Almshouse, was built in West Philadelphia, with its expansive grounds encompassing much of the southern portion of today’s Penn’s campus. With the closure of the central city almshouse in 1835, Blockley became the city’s almshouse.6

There were two potter’s fields at the Blockley Almshouse. A large one—the one described in newspaper accounts and extant reports, today designated by archeological investigators as Blockley Almshouse Cemetery #1—was located underneath what is now Franklin Field and surrounding streets; a smaller burial ground—Blockley Almshouse Cemetery #2—was situated approximately underneath the eastern side of Curie Boulevard above University Avenue.7 The large Blockley potter’s field was a resting place for indigents unable to negotiate burial elsewhere or whose bodies were unclaimed by relatives. The burial ground was described in one newspaper’s lurid terms as a “horrible place,” unfit to fulfill the purposes of Christian burial, where bodies were tossed into trenches and where some were taken by snatchers “before the coffins reached the graveyard.”8 Members of the Guardians of the Poor, the board charged with Almshouse administration, noted of grave robbing in 1845: “That it occasions dread and anxiety in the minds of some of the inmates of this House, is a well known fact . . . and to be buried elsewhere is sometimes asked as the last and greatest favor.”9

Corruption by staff and physicians made the traffic in dead bodies possible, earning the Guardians of the Poor the popular moniker the “Board of Buzzards.”10 The lucrative theft from the Blockley grounds reached a point in 1860 that one member of the Guardians stated that he would have “preferred to see bodies openly carried away from the graveyards by medical students, to seeing the pockets of the Superintendent surreptitiously lined by the auriferous traffic.”11 Medical students dissecting these bodies attended prominent schools, including Jefferson Medical College and, as noted, the University of Pennsylvania, as well as smaller, now-defunct Philadelphia institutions like the Eclectic Medical College.12 Bodies from the Blockley grounds may even have been a Philadelphia export: one report speculates that bodies from the Almshouse were sent to New York.13

Bodies interred at cemeteries favored by wealthy and middle-class Philadelphians rested undisturbed, unlike those buried in the Almshouse's large potter’s field. A case in point: In 1882, as remains were being moved from Asbury Cemetery, at 33rd and Chestnut Street, to Mount Moriah Cemetery, at 62nd and Kingsessing Street, a reporter noted, “There are no indications that ghouls have ever desecrated the place.”14 Woodlands Cemetery also apparently avoided body-snatching scandals, despite its proximity to Blockley. Like similarly exclusive Laurel Hill Cemetery along the eastern bank of the Schuylkill, the Woodlands was part of the nineteenth century “rural cemetery movement,” in which wealthy Americans chose to have their bodies buried in cemeteries which were more spacious, greener, and often better walled, guarded, and maintained than many church graveyards and public burial grounds for poorer Americans.15

While Philadelphians of all classes feared body snatching, impoverished Black Philadelphians buried in potter’s fields and historically Black cemeteries were disproportionately subjected to the depredations of grave robbers. Due to racial segregation imposed in Philadelphia cemeteries like the Woodlands and Mount Moriah through the 1870s, the Black community created its own cemeteries, for example, Bethel Burial Ground in South Philadelphia and Olive Cemetery in West Philadelphia, between Marion and Belmont Avenues. The African Friends to Harmony Burial Ground at 41st and Chestnut Street, supported by an African American mutual aid society, served as a burial ground for the poorest African Americans, entailing no or nominal costs to the families of the deceased. Death certificates of individuals buried at the African Friends to Harmony Burial Ground show that some of them died at Blockley.16 The movement of their bodies to the African Friends to Harmony Burial Ground suggests the tension that the Almshouse presented for Black Philadelphians: the Almshouse had “a great reputation for this thing [dissection] among the negroes of the city; they believe firmly that when they go to this hospital they need never expect to come back alive. In consequence, it is only as a last resort that they apply for admission to this institution.”17

One of the most infamous cases of grave robbing in Philadelphia's African American community occurred at Lebanon Cemetery in South Philadelphia. On the uncovering in 1882 of a grave robbing scheme that had taken hundreds of bodies from the cemetery to Jefferson and other Philadelphia medical schools over many years, both white and black Philadelphians rushed to protest the injustice.18 Black Philadelphians, on learning about the scandal, held an “indignation meeting” to voice their anger about the body snatchers.19 Within a year, the Pennsylvania Anatomy Act of 1883 was passed, making more cadavers legally available for dissection and increasing punishments for body snatching, largely ending the theft from private cemeteries.20 However, passage of Anatomy Act did not mean that bodies from the Almshouse were no longer dissected: a 1888 newspaper article on the dissecting room at the University of Pennsylvania describes the legal use of bodies of paupers from Blockley for dissection at medical schools across the City.21

In some cases, remains from the Almshouse were kept as specimens long beyond the close of a dissection course. Bones and preserved soft tissue specimens from Blockley are listed in the inventories of nineteenth century anatomical and pathological collections in the City, including the Wistar and Horner Anatomical Collection (later the Wistar Institute), the Mütter Museum, and the Academy of Natural Sciences. Dr. Samuel George Morton, who was resident Almshouse physician in the 1830s, collected the skulls of over two dozen white and black Philadelphians from the institution.22 Morton measured these skulls as part of his white supremacist racial science of comparing brain size and displayed them at the Academy of Natural Sciences with some thousand other skulls from across the world. In 1966, the skull collection was acquired by the Penn Museum, built on former grounds of the Almshouse, and at the edge of the potter’s field where the socioeconomic and racial inequalities of nineteenth century Philadelphia were extended into death.

In 2001, workers at a parking garage construction site on land acquired by the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) on the eastern side of Curie Avenue above University Avenue uncovered human skeletal remains. This was the smaller burial ground of the old Blockley Almshouse, which a private archaeological firm hired by Penn, identified as Blockley Almshouse Cemetery #2.

The University and CHOP jointly, and successfully, petitioned Philadelphia’s Court of Common Pleas for permission to remove the remains for reburial at the Woodlands Cemetery. The archaeological report for the excavation site reads: “Cemetery removed; site was impacted in 2001 by construction for a new parking garage. Excavated soil from the site—including an unknown number of human remains—was removed from the site and reportedly used as landfill beneath the FedEx Shipping Center in Gray’s Ferry. The remainder of the almshouse remains, including full interments and deposits of medical specimens, were archaeologically exhumed (by the authors of this report) and reburied in the nearby Woodlands Cemetery.” As for Cemetery #1, the archeological report states: “Current status unknown; possibly destroyed. Burials within this cemetery were disturbed by construction for the Keystone Battery Armory in 1889–1890 (Philadelphia Inquirer, October 29, 1889 and December 28, 1890), and again during the construction of Franklin Field, in the early 1920s.” It is indeed an open question if human skeletal remains, intact or fragmented, still lie under Franklin Field.23

1. “The Resurrectionists,” 11 January 1866, Evening Telegraph (Philadelphia), accessed from https://www.newspapers.com/image/85292402, 5 February 2021.

2. Edward Halperin. “The Poor, the Black, and the Marginalized as the Source of Cadavers in United States Anatomical Education,” Clinical Anatomy 20, no. 5 (2007): 489-495.

3. Michael Sappol, A Traffic of Dead Bodies: Anatomy and Embodied Social Identity in Nineteenth-Century America (Princeton University Press, 2001), 106.

5. Harold Abrahams, The Extinct Medical Schools of Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1966), 429-30.

6. John Welsh Croskey (ed.), History of Blockley: A History of the Philadelphia General Hospital from Its Inception, 1731-1928 (Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Co., 1929). Patients were first moved from the central city almshouse in 1832, during the cholera epidemic, when just one building was erected. The available evidence shows that the whole Blockley complex was opened and made the primary almshouse in 1834; the central city site was closed and sold in 1835. The dates 1832, 1834, 1835—and sometimes 1830, when the City purchased the Blockley land—appear in the literature. See Charles Lawrence, History of the Philadelphia Almshouses and Hospitals (Philadelphia: Author, 1905), p. 116; Croskey, History of Blockley.

7. Appendix A, “Potter’s Fields and Almshouse Cemeteries in Philadelphia,” in Douglas Mooney and Kimberly Morrell, “Phase IB Archaeological Investigations of the Mother Bethel Burying Ground, 1810–circa 1864,” prepared for the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, 11 October 2013, accessed from https://bethelburyinggroundproject.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/2.pdf, 5 February 2021.

8. “Ghouls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 November 1862, accessed from https://www.newspapers.com/image/167548681/, 5 February 2021

9. D.C. Humphrey, “Dissection and Discrimination: The Social Origins of Cadavers in America, 1760-1915,” Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine 49, no. 9 (1973): 819–827.

10. Lawrence, History of the Philadelphia Almshouses and Hospitals, 137, 208.

12. Abrahams, Extinct Medical Schools.

13. “Ghouls,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 November 1862, accessed from https://www.newspapers.com/image/167548681/, 5 February 2021.

14. “Moving a Graveyard,” The Times (Philadelphia), 29 December 1882, accessed from https://www.newspapers.com/image/52221816/, 5 February 2021.

15. Sappol, Traffic of Dead Bodies, 35; René L.C. Torres, “Cemetery Landscapes of Philadelphia,” (M.A. thesis, University of Pennsylvania, 1997), accessed from https://repository.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1494&context=hp_theses, 5 February 2021.

16. Names of individuals buried at this cemetery listed by Donna Rilling, “African Friends to Harmony Burial Ground,” Nomination of Historic Building, Structure, Site, or Object, Philadelphia Register of Historic Places, Philadelphia Historical Commission, 2018, accessed from https://www.phila.gov/media/20190401093121/4111-23-Chestnut-St-nomination.pdf, 5 February 2021; death certificates for these individuals available through digitized Philadelphia City Death Certificates, 1803-1915, on FamilySearch.org., accessed from https://www.familysearch.org/search/collection/1320976, 5 February 2021.

17. J. Howe Adams, Life of D. Hayes Agnew, M.D., L.L.D. (Philadelphia: F.A. Davis Company, 1892), 90.

18. “Ghouls To Be Tried,” The Times (Philadelphia), 9 December 1882, accessed from https://www.newspapers.com/image/52203339, 5 February 2021; Horace Montgomery, “A Body Snatcher Sponsors Pennsylvania's Anatomy Act,” Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 21, no. 4 (1966): 374-93.

19. “Colored People Crying Vengeance,” The Times (Philadelphia), 8 December 1882, accessed 5 February 2021 via https://www.newspapers.com/image/52203311; “Colored Citizens Roused,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 December 1882, accessed from https://www.newspapers.com/image/247875929, 5 February 2021.

20. “Anatomical Law of the State of Pennsylvania, Enacted June 13, 1883,” Science 3, no. 55 (1896): 84-86.

21. “Among the Stiffs,” The News (Newport, Pennsylvania), 1 February 1888, accessed from https://www.newspapers.com/image/310287951, 5 February 2021.

22. Samuel George Morton, Catalogue of the Skulls of Man and the Inferior Animals (Philadelphia: Merrihew and Thompson, 1849).

23. “10 Skeletons Discovered at Construction Sites,” Daily Pennsylvanian, 5 March 2001; “Gazetteer: Reburying the Past,” Pennsylvania Gazette, May/June 2002; Mooney and Morrell, “Phase IB Archaeological Investigations.”