The Wistar Institute: From Anatomical Museum to Biomedical Research Center

Constructed in 1894 on land acquired from the Blockley Almshouse, the Wistar Institute has evolved to become a world leader in biomedical research focusing on vaccines, immunology, and the genetic basis of cancer.

Named for the anatomist Caspar Wistar, the Wistar Institute housed human and animal specimens and models that were integral to teaching anatomy to Penn medical students throughout the nineteenth century. Later the Wistar’s focus shifted toward biomedical research, and in the decades after World War II, its scientists undertook research in oncology and vaccine development, earning the Wistar’s designation as the country’s first cancer research institute in 1972.

The Wistar Institute is America’s first nonprofit institution of biomedical research and training. It is famous for the “Wistar Rat,” the most popular laboratory rat strain used in biomedical experimentation today, as well as major contributions to the development of multiple vaccines and pathbreaking cancer research. The Institute began very differently, as a collection of teaching aids and specimens for University of Pennsylvania medical students.1

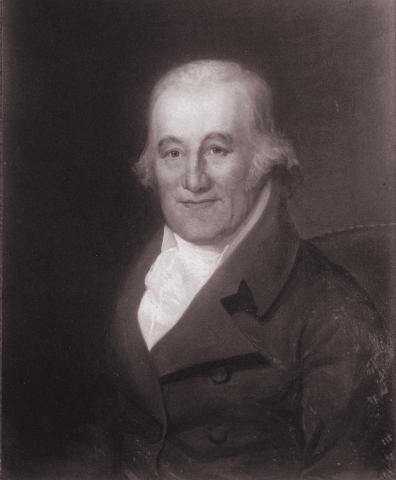

The Institute’s namesake is Caspar Wistar. Wistar trained at Penn’s medical school and took a degree in 1782, later becoming an adjunct professor of anatomy, midwifery, and surgery. Following the death of William Shippen in 1808, Wistar became professor of anatomy at the University of Pennsylvania.2 In 1802, Wistar began to order anatomical models from the sculptor William Rush. Around this time, more students were attending Wistar’s lectures, and he needed enlarged models of human anatomy visible to students in the back of the audience. These masterful large-scale papier-mâché and wood models, along with wax-injected specimens of human and comparative anatomy, were the foundation of Wistar’s collection.3

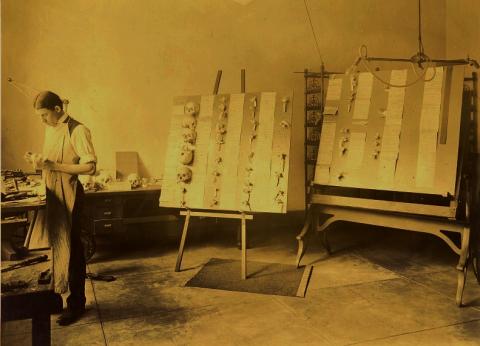

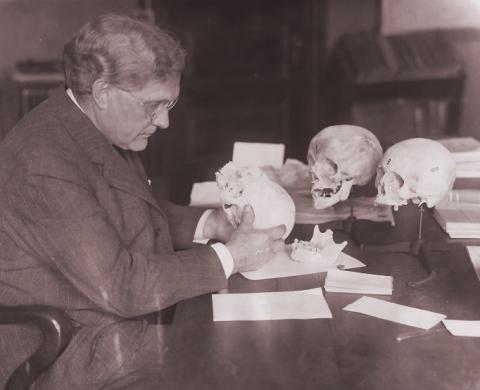

In 1816, Wistar appointed William Edmunds Horner to manage the collection.4 Horner added new specimens to the collection, including some acquired during tours of European anatomical collections and those donated by colleagues, publishing the first Catalogue of the Anatomical Museum of the University of Pennsylvania in 1832.5 Two more editions of the “Wistar and Horner collection” catalogue were published in 1836 and 1850 as the collection grew to encompass more human and animal specimens, some sourced from patients at the Philadelphia Almshouse and Pennsylvania Hospital.6 These anatomical models and specimens were an integral aspect of teaching anatomy at Penn’s medical school throughout the nineteenth century. The museum increasingly represented not only pathology and developmental and comparative vertebrate anatomy, but also included a collection of “racial skulls,” reflecting the entrenchment of ideas of racial difference in mid-nineteenth century medical teaching. Some of the physicians who donated skulls to the Wistar and Horner also provided skulls to Samuel George Morton’s cranial collection at the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia.

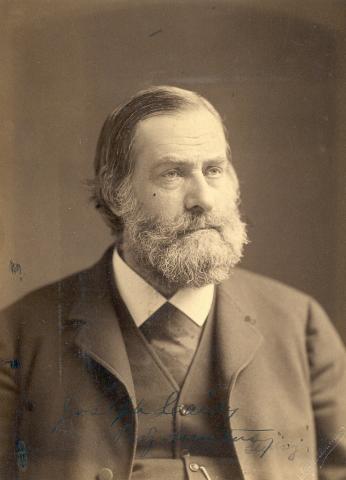

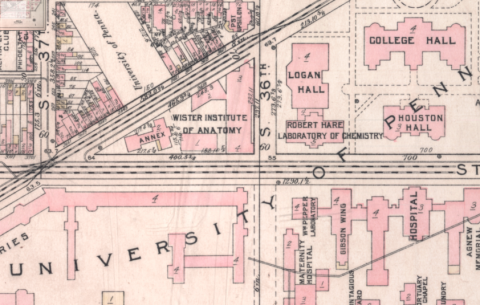

Following Horner’s death in 1853, curation of the collection was assumed by the Penn-trained physician and naturalist Joseph Leidy.7 During the time of Leidy’s directorship of the Wistar Collection, in 1872, Penn moved its campus from around Market and Ninth Street in the central city to its present location in West Philadelphia, on land that was formerly part of the Blockley Almshouse.8 The collection was stored on the top floor of Medical Hall (later renamed Logan Hall, now Claudia Cohen Hall), built in 1873. A prolific researcher, Leidy was named a professor of anatomy at the University, inheriting Horner’s position on the faculty. He was also heavily involved for over fifty years with the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia, served as a professor of natural history at Swarthmore College, and was president and curator at the Wagner Free Institute of Science for six years. The time commitments entailed by these arrangements diminished Leidy’s effectiveness as curator of the Wistar Collection. A fire in 1888 damaged much of Medical Hall and significant portions of the collection—a signal that if the collection were to survive and grow beyond Leidy’s death in 1891, it would need its own building separate from the University campus.9

The University’s provost at the time, William Pepper, was sensitive to this need; Pepper, another Penn medicine graduate, had himself served as the curator of the Pennsylvania Hospital’s anatomical collection earlier in his career. Pepper was able to secure funding from Caspar Wistar’s wealthy grandnephew, the lawyer and railroad magnate Isaac Jones Wistar, for a new fireproof building for the collection and support for research in medicine, independent from Penn but associated with it. This was the genesis of the Wistar Institute, founded in 1892. A new building was opened in 1894 at 36th and Spruce Street, and expanded in 1897.10

The first director, the zoologist Horace Jayne, restored and organized the anatomical holdings of the Wistar, which included the skeleton of a sixty-foot finback whale donated by the paleontologist Edward Drinker Cope and a collection of brains donated through pre-mortem agreements with wealthy and prominent white men who were members of the American Anthropometric Society, evidence of the persistence of the mid-nineteenth-century obsession with phrenology.11 (Unfortunately the poet Walt Whitman’s brain was mishandled and “spoiled” by a pathologist at the Wistar).12 Cope also donated his own brain and skeleton.13

Milton Greenman served as director from 1905 until 1937. In this period, the Wistar decisively turned away from its historic focus as a teaching and comparative anatomical collection toward biomedical research, perhaps most influentially, breeding the first rat used as a model organism, the albino “Wistar Rat.” The biologist Helen Dean King was crucial to the development of this line of rats.14 The Wistar Press published hundreds of articles and periodicals in this period, including physical anthropology, embryology, and medicine, among many other topics. Edmond J. Farris, an expert on fertility, followed Greenman as director and expanded the former’s turn toward modern laboratory biological research.

It was the directorship of Hilary Koprowski, a Polish émigré virologist—the first scientist to develop an effective oral polio vaccine—that fundamentally reshaped the institutional direction of the Wistar Institute after World War II. From 1957 until 1991, Koprowski steered the Wistar toward research in vaccine development and oncology, earning the Wistar a designation as the country’s first cancer research institute in 1972. During this time, Koprowski dispensed with the old Wistar museum collection; the collection was transferred to various museums across the country. The finback whale ended up at the Chicago Field Museum, while the majority of the human skeletal collection went to the Penn Museum. In the 1950s, a curator at the Wistar was alleged to have stolen some objects and anatomical specimens from the collection. Some were later found in a storage locker after his death and sold privately; pieces from the old collection have occasionally surfaced around Philadelphia.15

The Wistar Institute is currently a world leader in biomedical research, focusing on vaccines, immunology, and the genetic basis of cancer. Its facilities were expanded in the 1970s and 2010s, and it now plays a major role in both research and training of students at the University of Pennsylvania. The museum that was the germ of the Wistar Institute no longer exists, although its collection remains in institutions across Philadelphia and beyond.

1. Wistarabilia: 125 Years of Research Achievements and Improving Human Health (Philadelphia: Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology, 2017).

2. “Caspar Wistar, 1761–1818,” https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-people/biography/caspar-wistar.

3. Manieke Hendrickson, “Wistar’s Models: Knowledge and Skill in Anatomical Modelling in Philadelphia Around 1800,” Fugitive Leaves, blog from Historical Medical Library, College of Physicians of Philadelphia, https://histmed.collegeofphysicians.org/wistars-models/#_ftn1.

4. Biographical note, William Edmonds Horner Papers, https://archives.upenn.edu/collections/finding-aid/upt50h816; Charles H. Goudiss and Joseph Walsh, “Notes on the Life of Dr. William Edmonds Horner,” Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia vol. 14, no. 4, December 1903, pp. 423-438.

5. Wistar Institute of Anatomy and Biology, “Catalogue of the Anatomical Museum of the University of Pennsylvania: with a Report to the Museum Committee of the Trustees, November, 1832,” U.S. National Library of America Digital Collections, https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-61140340R-bk.

7. W. S. W. Ruschenberger, “A Sketch of the Life of Joseph Leidy, M.D., LL. D.,” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 30, no. 138, April 1892, pp. 135-184.

8. “Penn Campuses Before 1900,” https://archives.upenn.edu/exhibits/penn-history/campuses/ninth-street-campus.

9. George E. Thomas and David B. Brownlee, Building America’s First University: An Historical and Architectural Guide to the University of Pennsylvania (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2000), 176.

11. Mickey Herr, “On the Hunt for Brains, Discovering the Wistar Institute,” Hidden City, 21 February 2018, https://hiddencityphila.org/2018/02/on-the-hunt-for-brains-discovering-the-wistar-institute/.

12. James R. Wright Jr, “Henry Ware Cattell and Walt Whitman’s Brain,” Clinical Anatomy 31, no. 7 (2018): 998– 996.

13. Jane Pierce Davidson, The Bone Sharp: The Life of Edward Drinker Cope (Philadelphia: Academy of Natural Sciences, 1997.

14. Mickey Herr, “Queen of the Rats: How One Female Scientist Colonized the Modern Lab, Hidden City, 16 July 2018, https://hiddencityphila.org/2018/07/queen-of-the-rats-how-one-female-scientist-colonized-the-modern-lab/

15. Wistar Institute, “Hilary Koprowski (1916- 2013),” 13 April 2013, https://wistar.org/news/blog/hilary-koprowski-1916-2013; Wistar Institute, “Our History,” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X_c7q-vYjy0; Eric C. Rodenberg, “Rare, Old Bottle Found in Nearby Museum,” http://www.antiqueweek.com/ArchiveArticle.asp?newsid=2549;