Backstory: Chicago’s Union Stock Yards and Turn of the Century Red Meat Wars

In the late nineteenth century, the epicenter of the refrigerated “dressed” beef industry was the Union Stock Yards of Chicago.

The Union Stock Yards of Chicago was the massive centralized livestock gathering site that was the home base for the dressed and refrigerated beef industry (“industrial beef”) in the United States. By 1890, all aspects of this industry were controlled or dominated by four meatpacking corporations: Armour, Swift, Hammond, and Morris.

The perfection of the refrigerated railroad car in the 1870s made it possible for Chicago meat to travel throughout the continent. Chicago packers then began to wage fierce price wars against local slaughterhouses and butchers in markets from New York to San Francisco. While “home town” interests had the advantage of consumer preferences for fresh, locally-produced meat, the Chicago packers eventually prevailed over most of their rivals because of Chicago’s proximity to western cattle ranges, low freight costs (a consequence of the city’s location on multiple, competing rail lines, as well as the sweetheart deals packers secured from the railroad companies), greater economies of scale in production because their operations were so large, and a remarkable penchant for efficiency. 1

The latter half of the nineteenth century witnessed a fierce competition for control of red meat production and distribution in the United States. The Union Stock Yards of Chicago was the epicenter of this conflict. And it was an enterprise that defined the era of industrialized meat production and distribution in the United States. Writes the sociologist Amy Fitzgerald, “The ‘Union Stock Yard era’ in slaughterhouse history, which refers to the concentration of animal slaughter in a few urban areas during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, was driven by the idea that it was more efficient for animals to be slaughtered in central locations and to transport carcasses to markets than to transport live animals.”2

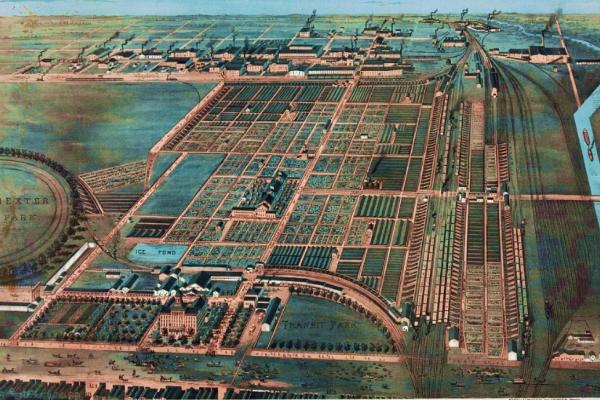

In 1864, nine railroad companies formed the Union Stock Yard and Transit Company to build and operate a centralized stockyard complex on a 320-acre site that stood just outside the city. The Union Stock Yards, the world’s largest complex of its kind, opened on Christmas Day 1865. Offshoot tracks from the main railroad lines carried livestock deliveries to the stockyards; drovers emptied the railroad cars of cattle, hogs, and sheep and herded them into the pens. The Yards’ source of water was the Chicago River, which, unfortunately, was also the endpoint depository, via contaminated “Bubbly Creek,” for the Yards’ waste. By 1900 this vast enterprise at Exchange and Halsted streets encompassed 475 acres, with 50 miles of roads and 130 miles of track.3

The Union Stock Yards collected a staggering volume of cattle. Receipts compiled over a fourteen-year period (1865 to 1879) show a cumulative figure of 10,165, 456 cattle, with more than 1 million recorded annually from 1876 to 1879.4

In 1860, beef cattle butchering was local or regional. Nearly fifty years later, as the historian Jonathan Specht writes, “. . . an animal could be born in Texas, slaughtered in Chicago, and eaten in New York. Americans rich and poor could expect beef for dinner. The key aspects of modern beef production—highly centralized, meatpacker dominated, and low cost—were all pioneered during the period.”5 This transformation was orchestrated by the Big Four meatpacking companies—Armour & Co., Swift & Co., Hammond & Co., and Morris & Co.—whose competitive advantage in the nation’s beef markets rested on the guarantee of “bigger steaks at cheaper prices.” Their administrative offices and meatpacking operations were located on the peripheries of the Union Stock Yards.

The refrigerated car was the technological driver of so-called industrial beef. This innovation’s success depended on the meatpacking corporations’ reorganization of business practices to control every stage of industrial beef from “hoof to table.” It also, as Specht tells us, depended on a second factor, the exploitation of cheap immigrant labor.

“A packinghouse, Specht writes, “was a masterpiece of technological and organizational achievement, but that was not enough to slaughter millions of cattle annually. Packing plants needed cheap, reliable, and desperate labor. Fortunately, they found it in the combination of mass immigration and a legal regime that empowered management, checked the nascent power of unions, and limited liability for worker injury.”6 “Back of the Yards,” where many of these workers lived, was a notorious slum district in the shadow of the stockyards, “characterized by extreme poverty, crowded conditions, delinquency, and environmental pollution.” Upton Sinclair’s classic muckraking novel, The Jungle, described the harsh life and labor of the immigrant poor in the Big Four’s lair.7

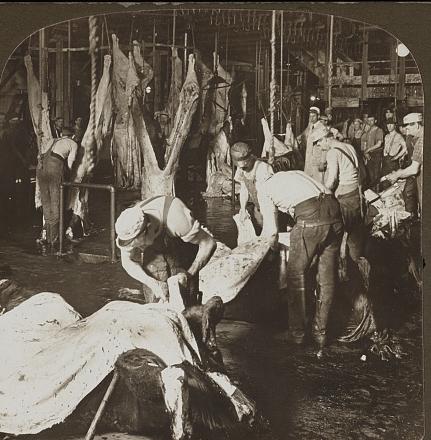

Industrial beef was “dressed” on a continuous-motion rail that carried carcasses on hooks once the animals had been killed—a process entailing a single blow, either “a hammer swing to the skull or a spear thrust to the animal’s spinal column”—and suspended from the rail. It was a “disassembly line,” whose economy and efficiency depended on cheap menial labor. The rail (trolley) was the only mechanized component of this process. As Specht cogently puts it, “. . . these plants relied on a brilliant intensification of the division of labor. . . . [T[he division of labor in meatpacking increased productivity because it simplified labor tasks in a process of de-skilling that made workers replaceable as well as allowing for a more total exploitation of labor through worker synchronization and pace setting. Workers . . . could be worked nearly to death.” Highly skilled butchers were the only skilled laborers in the reduction process; working at the final station in a separate room, they sliced carcasses into quarter chunks preparatory to refrigeration and railroad distribution.8

Dressed beef consumption was more or less universal after the turn of the century. The meatpackers were able to directly control everything but the railroads that hauled the refrigerated cars, and were forced to compete for this business. As long as cattle were being shipped live from distant markets to the East Coast via Chicago (meat on the hoof), the railroads held a commanding position in red meat distribution. By 1890, this was no longer the case; there were too many railroads, too many rail lines; when Swift, Armour, and the others built their own refrigerated cars, the railroads were compelled to accept lower haulage prices than had been the case with live cattle.

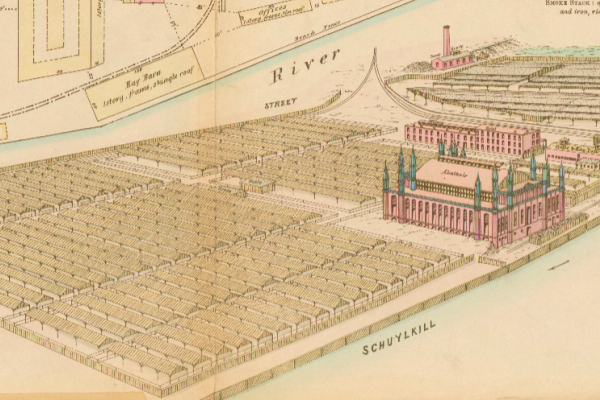

As our Philadelphia case (described in our next “story”) illustrates, one major railroad, the Pennsylvania, created a kind of mini-Union Stock Yards in West Philadelphia and shipped dressed meat to retailers on the East Coast.

1. Thomas G. Andrews, “Making Meat: Efficiency and Exploitation in Progressive Era Chicago,” OAH Magazine of History, January 2010, pp. 37–40.

2. Amy J. Fitzgerald, “A Social History of the Slaughterhouse: From Inception to Contemporary Implications,” Human Ecology Review 17, no. 1 (2010): 62

3. “The Birth of the Chicago Union Stockyards,” Chicago Historical Society (2001), accessed from http://www.chicagohs.org/history/stockyard/stock1.html, 1 September 2020; “Union Stockyard,” Encyclopedia of Chicago; early contemporaneous sources include: “The Union Stock-Yards at Chicago,” Hearth and Home, 16 April 1870; “The Chicago Stock-yards, American Artisan, 24 May 1871.

4. “Total Receipts at the Union Stock-Yards for Fourteen Years, The Hub (New York), 1 December 1880. Receipts also shown for hogs and sheep in the millions.

5. Jonathan Specht, Red Meat Republic: A Hoof-to-Table History of How Beef Changed America (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2020, 1–2.