Efficiency under One Roof: D.M. Martin Co.’s One-Size-Fits-All Slaughterhouse

From 1908 the D.M. Martin operated a centralized, state-of-the-art, “all in one” slaughterhouse enterprise near 30th & Market St., catty-corner to the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Philadelphia Stockyards.

In 1908, the D.B. Martin Co., a major East Coast meatpacker, opened a state-of-the-art slaughterhouse building on the southwest side of Market St. opposite the Pennsylvania Railroad’s Philadelphia Stockyards. Every phase of slaughtering and converting live cattle to dressed meat took place under one roof.

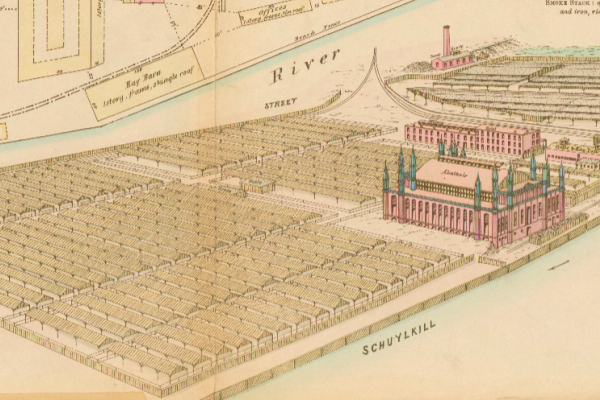

In 1876, D.B. Martin founded the D.B. Martin Company in Delaware (USA), and later (1904) incorporated the company in Philadelphia (USA). A processor of animal-derived fats, oils, fatty acids, soaps, and fibers, the company experienced rapid growth in the United States and Canada, becoming the largest meat packing and processing operation east of Chicago. Martin contracted architect C.B. Comstock to design a state of the art, all-in-one facility in Philadelphia at a cost of $1,000,000. Opened in 1908, the building incorporated an abattoir, corporate headquarters, office space, rooftop stock pen, cold storage, and oleo processing operations, along with advanced environmental controls to protect city residents.1

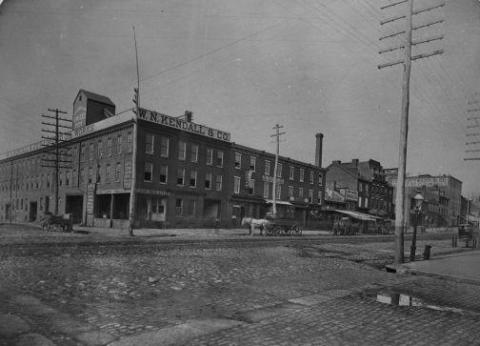

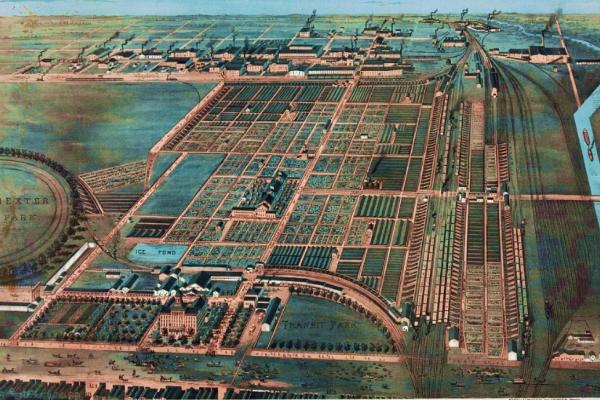

For at least a dozen years, the D.B. Martin Co. operated its “state of the art” slaughterhouse in the shadow of the neighboring, sprawling, less technologically sophisticated Philadelphia Stockyards, operated under the auspices of the Pennsylvania Railroad. An archival photograph from 1881 shows a precursor building to D.M Martin on the southwest corner of 30th and Market St. with a rooftop sign identifying it as the W.N. Kendall Company. A comparison of the 1881 image with photographs of the building on this site during the D.M. Martin era suggest that the architect C.B. Comstock’s design was a replacement building to accommodate the company’s commerce in dressed meat. (See and compare Related Images.)

What did “state of the art” mean? Dennis Carlisle, for Hidden City, provides the following succinct description of a vertically organized enterprise.

Behind a 2.5 story façade of limestone, terra cotta, and high-fire bricks facing both 30th and Market Streets laid [sic] a 4.5 story (counting the basement and first floor that stood on the on the lower grade [a split-level structure] under 30th and Market) steel frame, reinforced concrete, fireproof fortress. The asphalt-floored killing room was on the second floor. Here 2,000 cattle a week turned to meat. Cattle parts were dropped into chutes leading to different areas of the building. Meat fed into the cold storage rooms on the first floor, while hides and fat fed into rendering and pickling rooms in the basement. Cattle waste went to the first floor. Moisture was separated out and the remainder made its way over to the loading docks to be shipped to one of the company’s many fertilizer plants.2

The meatpacking entrepreneur Gustavus F. Swift (of Swift & Co.) pioneered mechanized, vertically integrated slaughterhouse architecture in the late-nineteenth century. Swift’s model was a structure that let gravity do its part, moving the carcasses of animals killed on the top floor downward through the building.3

One D.B. Martin Co. novelty was to hold cattle in rooftop pens, some 500 at a time, preparatory to moving them downward in their transition from meat-on-the-hoof to carcasses rendered for beef and sundry byproducts. There’s no denying this was an upgrade from what the Pennsylvania Railroad was doing within eyeshot of D.B. Martin’s operations. Compare this to “the stench of iron works, lead works, coal yards, and varnishmakers [blending] with the aroma from acres of cattle and hog pens” on the north side of Market in the vicinity of 30th St.4

In 1920 D.B. Martin Co. was partnered with Wilson & Co., a meatpacking giant whose headquarters, since 1916, were located in the Union Stock Yards, where the company was a rival to Swift and Armour.5 Carlisle writes that by 1930, Wilson & Co. was using the former Martin building to produce “curled hair”—“upholstery filler made from the tails and fur of horses, cows, and hogs”—production that entailed only partial use of the building; to fill the remainder, Wilson & Co. leased space to other companies for poultry and soap production. Amazingly, the old Martin building would survive enormous changes on Market St. in the coming century—the construction of 30th St. Station, the US Post Office (now IRS) on the opposite side of the of the former abattoir’s 30th St. entrance, the arrival of the Drexel Institute (now University) on adjacent western blocks—and unrealized city plans that would have removed it. Today the building is home to offices and a popular tavern, one among several restaurants that have used the building in recent years. Interestingly, one of its earlier uses, from 1956, was as headquarters for the Atlantic Division of Atlantic & Pacific (A&P).6

1. “INOLEX,” Wikipedia; see also INOLEX Inc., https://inolex.com/pc/About/History.

2. Dennis Carlisle, “Slaughterhouse 3000 (Market Street), Hidden City: Exploring the Urban Landscape (Architecture), 13 May 2013, https://hiddencityphila.org/2013/05/slaughterhouse-3000-market-street/.

3. Lindy Boggs, The Rational Factory: Architecture, Technology, and Work in America’s Mass Production (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), 26–30.

4. Carlisle, “Slaughterhouse 3000 (Market Street).”

5. “Wilson & Co.,” Encyclopedia of Chicago, http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1512.html.

6. Carlisle, “Slaughterhouse 3000 (Market Street).”