The Final Years of the Arena

Part of

White outmigration, owner turnover, and construction of the Spectrum brought the Arena to its final years of operation.

The final years of the Arena were signaled by the departure of its regularly-hosted professional sports teams from Philadelphia. When the Arena’s long-time manager retired, he decided to sell the building at auction. A series of owners followed and the lack of stable leadership, partnered with decreased crowd attendance, made the Arena unprofitable. During its final 17 years of operation, the Arena experienced four different owners, a name change, increased violence, smaller crowds, and competition from the newly constructed, larger Spectrum stadium in South Philadelphia. The Arena finally closed for good in 1981 when it was allegedly set ablaze by one of its owners.

In 1962, the Warriors left the Arena for good, moving to San Francisco and shaking Philadelphia’s confidence in its claim to be a professional sports city.[1] The Ramblers moved to Cherry Hill, taking Philadelphia’s professional hockey team with them.[2] The winter and indoor major sports landscape in Philadelphia had evolved and changed markedly between the Second World War and the mid-1960s. White outmigration to the region’s suburbs left the city as a whole strapped for tax dollars, and West Philadelphia was no exception. During its final years, the Arena stood partially filled, in desperate need of tenants and responsible owners.

In 1965, Pete Tyrell, the longtime manager and part-owner, whose name was synonymous with the Arena, retired. In an interview with the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, Tyrell recalled the glory days of the Arena, when it hosted two boxing nights a week—one match between Ace Clark and George Godfrey drawing 11,000 spectators—the Ringling Brothers Circus, and the Roy Rogers rodeo.[3] Those days had passed. Following Tyrell’s departure, the Arena Corporation decided to sell the aging venue.

Local boxing promoter James Toppi took ownership of the facility when the Arena was auctioned in 1965. Toppi had experience managing some of Philadelphia’s local small sports and entertainment venues. He promised to invest in the Arena—repair leaking floors in the balcony, fix the building’s faulty lighting, install more bathrooms, and, in other ways, bring the Arena into modern America.[4]

Toppi pledged local boxing as the future of the Arena.[5] He began booking more boxing matches and screening for major boxing matches from across the country. He was able to book local hero Joe Frazier for a card, which recalled the time when Benny Bass had fought Cleto Locatelli before 12,000 densely packed spectators.[6]

In addition to boxing, Toppi’s lineup for the Arena included: the “World Series of Jazz,” featuring Miles Davis; a Nation of Islam political rally; and simulcasts of live sporting events, operas, and even a bullfight.[7] Yet for all this activity, the Arena was behind the times.

The city’s construction of the Spectrum in South Philadelphia signaled the Arena’s demise as a major indoor venue in Philadelphia. When the Syracuse Nationals basketball team moved to Philadelphia in 1963, the team (now the Philadelphia 76ers) used the Arena (and the Civic Center) as a temporary home court. The multifaceted, spacious Spectrum became their permanent home court when it opened in South Philadelphia four years later.[8] Opened in the fall of 1967, the Spectrum could seat 15,000 spectators for hockey and 18,000 for basketball.[9]

The Arena continued to showcase boxing in Philadelphia, but the venue was increasingly dangerous. Incidents during the 1968 boxing season included bottle-throwing in crowds and at boxers.[10] In 1969, a policeman was shot and five others were stabbed at a rock concert.[11] For a decade, the Toppi family (James’s wife, Edna, took over after his death) promoted boxing and other events at the ailing Arena, but 10 years after purchasing the Arena, the Toppi family had to put the building up for sale.[12]

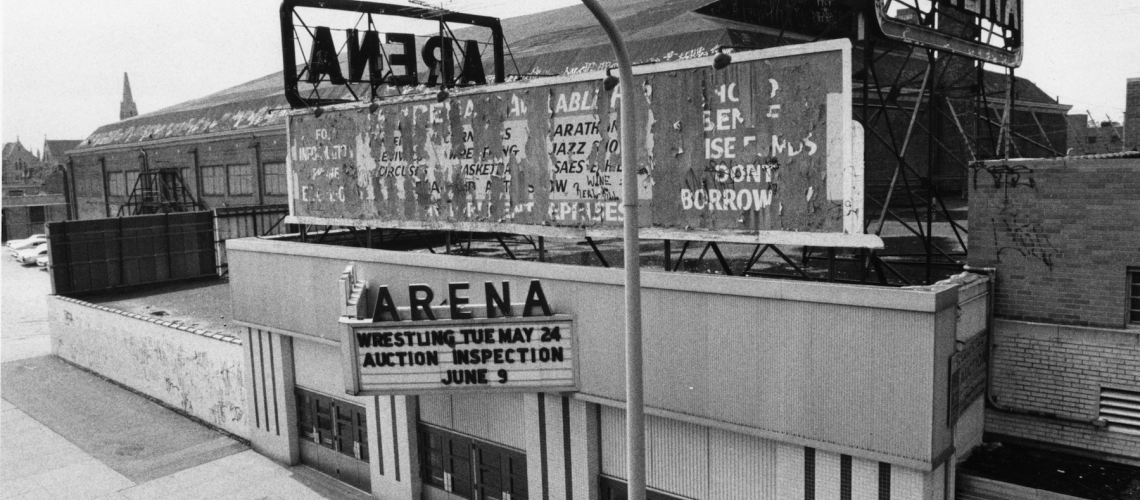

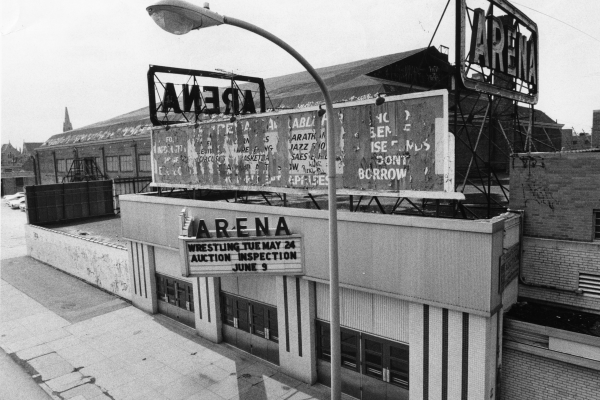

Photos of the Arena at this time show a building in disrepair with a sad marquee in a desolate neighborhood.[13] In a retrospective piece on the Arena, Pete Tyrell’s wife cited a series of incidents that she thought pointed to a changing neighborhood and an unsafe environment for business.[14] In 1977, Edna Toppi sold the Arena for $165,000, just a fraction of the cost to build it 60 years earlier.[15] Its new owner, Randell Wright, a recently out-of-jail auto chop-shop owner, had outbid only a handful of competitors.[16] After running minor boxing events and showing closed-circuit live boxing matches, Wright sold the Arena to Larmark, Inc. in 1980 for $100,000.[17]

Larry Lavin, the Arena’s last owner, was a Penn dental student—and, reportedly, the leader of a drug ring in Philadelphia. Lavin created Larmark Inc. (a cover corporation combining his and his associate, Mark Stewart’s name) and bought the Arena to have a legitimate business in his portfolio.[18] Lavin and Stewart rechristened the Arena the Martin Luther King Jr. Arena to appeal to West Philadelphia’s African American residents.[19] On its opening night, on June 20, 1980, crowds stood in line around the block to get tickets to see the Sugar Ray Leonard-Roberto Duran fight, which was broadcast on a closed-circuit screen. The satellite dish that was newly installed didn’t work, and customers still waiting outside reacted by breaking windows and knocking down doors.[20]

Stewart tried to bring professional basketball back to the corner of 45th and Market in 1980 with his new team, the Philadelphia Kings; he hired former 76ers star Hal Greer to oversee the operation of the Arena, as well as to coach the Kings.[21] Greer and Stewart would struggle to fill the Martin Luther King Jr. Arena. The Kings played before high-school-sized crowds. To try to offset the basketball shortfall, Greer and Stewart recruited roller derbies and shyster evangelists, one of whom claimed to raise someone from the dead in a service at the Arena.[22]

In the fall of 1981, Lavin decided he had had enough, and he ordered his business associate Stewart to close the Arena.[23] A week after that conversation, a headline in the Philadelphia Inquirer reported, “King arena damaged by blaze.” Stewart had allegedly ordered the torching, trying to recoup the losses that he and Lavin had incurred.[24] Two years later another arson fire would consume the abandoned structure.[25]