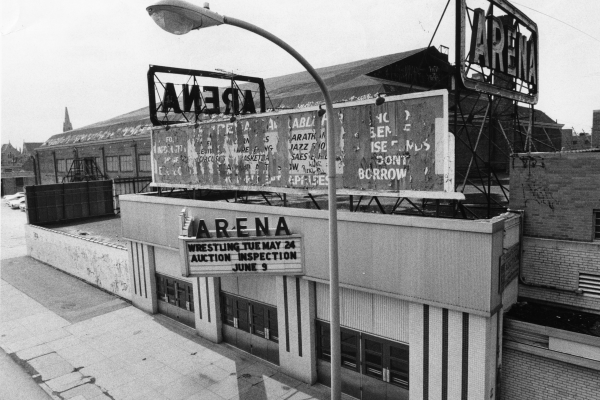

The Early Years of The Arena

Part of

The Arena began as an ice rink, but quickly expanded to an arena used for events like boxing matches, rodeos, and major political events.

The Arena originated in 1920 as “the Philadelphia Auditorium and Ice Palace” for ice hockey games and the occasional boxing match. In 1927, new ownership renamed the stadium “The Arena” to reflect the inclusion of non-ice sports. It also became a multi-purpose facility that hosted tennis matches, rodeos, and even political gatherings.

Before the Arena, ice skating and ice hockey were strictly outside seasonal activities. Images of winter sports are conspicuously absent from the sports section of Images of America: Philadelphia, The World War I Years. The lack of ice hockey in this collection reflected the lack of facilities large enough to accommodate the sport.[1]

Convinced that a strong yet untapped regional market existed for ice hockey, George Pawley set out to put Philadelphia on the map as a top-rated winter sports city by constructing an indoor ice rink. He was sold on the idea by George Orton, a local track and field star and ice hockey amateur. The rink would be strategically located at the southeast corner of 45th and Market streets adjacent to the Market Street Elevated’s 46th Street station, an easily accessible train ride from Center City.

Pittsburgh capitalist Hunt Miller originally backed the project, but Miller endangered Pawley’s dream when he went bankrupt during the construction. Pawley soon found another backer in Jules Mastbaum, a Philadelphia entertainment magnate operating movie theaters throughout the city.[2] Mastbaum’s investment sustained the construction at a cost later estimated at $800,000.[3] At that time it was the largest indoor ice rink in the nation.[4]

On February 14, 1920, the Philadelphia Auditorium and Ice Palace opened to an excited crowd for its inaugural event, a hockey game between Princeton and Yale. However, few (if any) of the attendees even knew the rules of hockey. As a promotion, Pawley had announced the rink would be open to the public after the game. The crowd was excited to skate on a rink the New York Times had called “the finest in the nation” for ice skaters a few weeks earlier.[5] Not realizing that there were three periods in a game, the crowd rushed onto the ice at the end of the second period. The police had to clear the ice so the game could continue and Yale won 4–0.[6] Despite the confusion of the first night’s spectators, the Arena hosted games for colleges and amateur leagues throughout its first year.[7]

In 1927, Rudy Fried and Maurice Fishman purchased the Ice Palace and renamed it the Arena. The name change reflected the venue’s expansion to non-ice sports. Both Pawley and his successors were dedicated to making the Arena Philadelphia’s premier boxing venue.[8] It was a golden age of boxing in Philadelphia, with an abundance of young local talent.[9] As the 1920’s progressed, the Arena became West Philadelphia’s home for indoor sports, attracting nearly 200,000 fans during the 1929 season for hockey games and boxing matches. The Arena paid 280 boxers nearly $250,000 in the boxing season, and on the eve of the Great Depression, Fried and Fishman held 28 boxing cards and boasted the Arena’s largest gate receipts to date.[10]

As the Great Depression deepened nationwide, boxing clubs and sports venues shuttered their doors. The Arena did something unique, according to the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin, in order to remain open. In the early days of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s presidential administration, the Arena accepted scrip from “anywhere in the country by banks or clearinghouses when used in the purchase of tickets.” The owners recognized the psychological benefits of having the Arena open for business in hard times as well having people employed and their families fed.[11]

The recently formed National Hockey League (NHL) found a home at the Arena during the 1930–1931 season when the Pittsburgh Pirates hockey team moved to Philadelphia and was renamed the Philadelphia Quakers. Lasting only a single season, the Quakers took three games to score their first goal and promptly folded at the end of 1931.[12] At the same time, the Arena began hosting the New York Rangers minor league team, the Philadelphia Ramblers, which would continue to play at the Arena throughout the 1930s and into early 1940s.[13]

Despite coal rationing during World War II, the Arena continued hosting boxing matches and hockey games. The Ramblers were replaced during the war with the Philadelphia Falcons, a team that had relocated from Atlantic City after the Army requisitioned the armory there.

The Arena became a center of winter entertainment with the introduction of the Ice Follies and the Ice Capades. General manager Pete Tyrell saw potential in this new form of skating entertainment.[14] Tyrell secured Olympic champion figure skater Sonja Henie to make her professional debut at the Arena.[15] The Arena was in safe and innovative hands with Tyrell. He assured the place of hockey, boxing, and ice shows in Philadelphia as well as a variety of off-ice entertainments. The Arena filled its spring and summer seasons with anything Tyrell could book: rodeos, tennis matches, dance marathons, and rocking-chair races.[16]

The Arena also hosted major political events, some of which focused on controversial topics. In 1928, 17,000 supporters packed into the 9,000-seat Arena to see presidential candidate Al Smith. Appealing to West Philadelphia’s Irish, Italian, and German immigrant communities, Smith railed against Prohibition.[17] On the eve of America’s entrance to World War II, the Arena hosted a rally for the non-interventionist America First Committee after the Academy of Music refused to host the event. The topic was so provocative that Arena managers checked with city officials to assure they were capable of accommodating the event within city boundaries in a time of perceived national emergency. Over 9,000 supporters packed the Arena to hear keynote speaker Charles Lindbergh. An estimated 6,000 supporters gathered outside the door. Lindberg’s fiery speech asserted America would not benefit from intervening in the war and repeatedly attacked President Roosevelt with accusations of going “beyond even Hitler” in what Lindbergh claimed was a desire for world domination.