Gender and Race at the Centennial Exposition

The Centennial Exposition marked a limited advance in women’s rights. The Exposition’s leaders and the fair’s exhibits perpetuated prevalent cultural stereotypes of blacks and Native Americans.

The Women’s Pavilion showcased the industrial and artistic achievements of American women for an international audience. Although the organizers’ political activism was limited, the Women’s Pavilion helped advance the cause of women’s rights through its displays. White racial prejudices and invidious cultural stereotypes prevailed with respect to the fair’s treatment of African Americans and American Indians.

Here we take up the Centennial Exposition’s treatment of marginalized groups in the post-Civil War era: Women, African Americans, and Native Americans.

Women

Women were instrumental in the financial development and design of the Centennial Exposition. “[T]hey planned, funded, and managed their own pavilion and devoted it entirely to the artistic and industrial pursuits of their gender.”1 Elizabeth Duane Gillespie, great-granddaughter of Benjamin Franklin and head of the Women’s Centennial Exposition Committee, was described by one of the executive committee members as the “imperial wizard, the arch-tycoon” of the Exposition.2 According to the historian Gary B. Nash:

Elizabeth Duane Gillespie led a female army through the city’s neighborhoods to sell subscriptions for the stock and obtain signatures for raising $1 million. Within two days, Gillespie’s army had 82,000 signatures and soon had generated letters of support from all over the nation that convinced Congress to lend $1.5 million to the Exposition’s organizers.

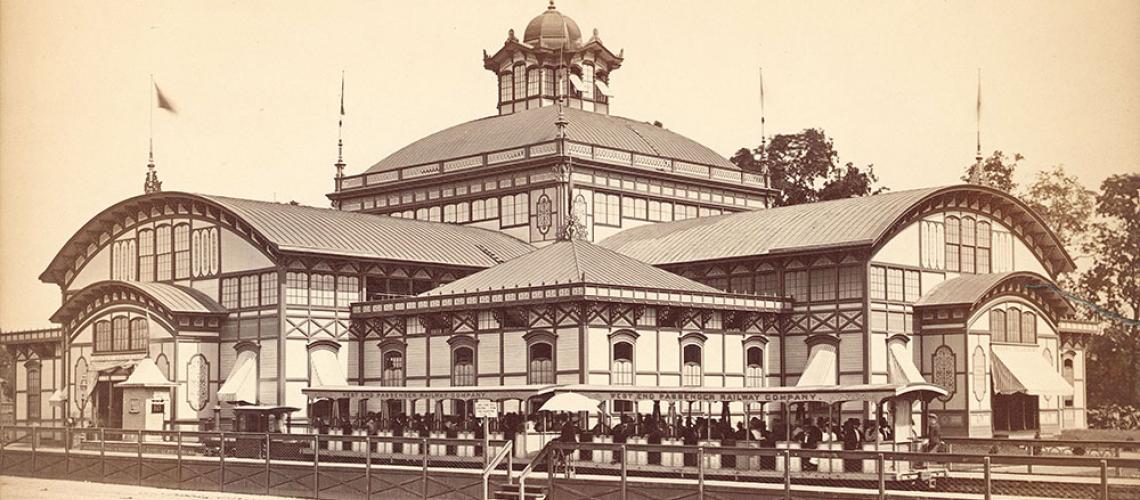

The Women’s Committee was also charged with mounting exhibits for the Main Building that would display the products of women’s labor. But the women’s insistence that foreign nations should be widely invited to exhibit, lest the Exposition become a narrowly conceived affair, ironically turned to their disadvantage. Foreign exhibitors came forward in such numbers that the Exposition’s director-general, just eleven months before opening day, informed the women that little room was left in the Main Building for their exhibits. Though angry at this last-minute decision, Gillespie’s committee rose enthusiastically to the challenge. In just four months, they raised more than $31,000 to erect the one-acre Woman’s Pavilion, the first at any world’s fair.3

The Women’s Pavilion was a popular Exposition attraction, with demonstrations of women’s contributions to the arts, sciences, education, and industry. Displays of female intellect, including 74 inventions patented by women, aimed to increase women’s confidence. Some of these inventions aimed to decrease the time and effort involved in performing household duties such as a dishwashing, sewing, and cooking, thereby relieving women of some of their traditional burdens in the home.

That said, the Women’s Centennial Committee was beholden in two respects to the Centennial’s male power brokers. The all-male United States Centennial Board of Finance had appointed these women in 1873 primarily to raise subscriptions for the Exposition. And the architect for the Women’s Pavilion was a male, Hermann Schwarzman, “chief engineer and designer of many buildings at the Exhibition.” (It turned out that a skilled female architect, Emma Kimball, of Lowell, Massachusetts, was available for the project.) It is also perhaps telling that no women artists were represented in the Memorial Hall Art Exhibit.

That said, these progressive women broke new ground in advancing women’s rights, first by putting American women’s formidable intellectual and material achievements on international display, second by publishing the New Century, “an eight-page weekly paper, printed on premises at the Woman’s Building and financed entirely by the Women’s Centennial Committee.” Edited by the Philadelphian Sarah Hallowell, this progressive journal advocated for women’s rights in the home and the marketplace. New Century authors “criticized unjust practices of industry, such as its hazardous, unhealthy, and immoral working conditions, its long, tedious hours of toil, and its meager monetary compensation for female wage-earners.”4

Yet these women eschewed political activism. And for this reason, they were repudiated by the National Woman Suffrage Association, whose leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage found nothing to celebrate in the nation’s first century. Indeed, the women of the NWSA interpreted this avoidance of politics as acquiescence in the patriarchal social order.

It is worth noting that before the century was out, Jane Addams and the women of Chicago’s Hull House, in the vanguard of the Progressive movement, would translate New Century-style advocacy for women, children, and organized labor into activist research for social and political change.5

African Americans

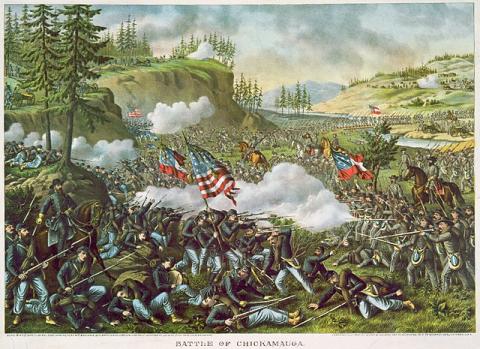

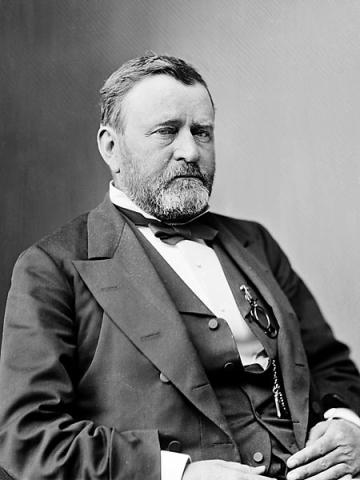

Celebrating a century of national progress, the Centennial Exposition was planned to stake America’s claim as a world industrial power. Staged in the final year of U.S. Grant’s presidency, which marked the end of Reconstruction, the Exposition also had “an explicit ‘mission of [white sectional] reconciliation,’” at a time when white-supremacist “redeemers” were seizing control of southern legislatures. One motto of the fair was “No North, No South, No East, No West—The Union One and Indivisible.” Quite simply, racial healing was not on the Centennial’s agenda. “[B]lack representation in all aspects of the Centennial Exposition was minimal.” The only jobs available to the few blacks who were employed at the Centennial were menial—waiters, janitors, and messengers. And the leadership class of northern blacks fought an uphill battle for representation at the fair.

African American men and women who tried to participate in fundraising efforts for the celebration met with discrimination, insult, and even physical injury. Frederick Douglass, arguably the greatest orator of his time, was invited to sit on the main platform on opening day, but was not invited to speak. Furthermore, he was almost denied entrance to the platform by police who refused to honor his ticket, incredulous that a black man would be welcome in the company of President Grant and the other dignitaries on the dias.6

The African Methodist Episcopal Church made a notable effort to commemorate black history and culture at the Centennial. The plan was to commission a statue of the AME’s founder, Bishop Richard Allen, whose home church was Mother Bethel AME, founded on Allen’s property at 6th and Lombard streets in Philadelphia. Allen achieved prominence not only as the founder of the first independent black denomination, but also as a vigorous anti-slavery spokesman and underground railroad organizer. Overcoming the objections of the Centennial’s organizers, the AME leaders in the monument campaign drew on church funds to commission a life-size bust of Allen that was to be mounted on a 22-foot-high “elaborate pedestal” and erected “midway between Fountain and State Avenues, and west of the Government Building.”

The bust was assigned to the Cincinnati sculptor Alfred White, reportedly an African American. The pedestal was likely the handiwork of the African American sculptor Edmonia Lewis, who resided in Rome and contributed several other works to the Centennial. The plan was to have the two pieces shipped from Cincinnati to Philadelphia by train, to arrive in time for a 12 June dedication. Logistical problems ensued on the production side, and the dedication was delayed until 22 September, a deadline that passed with no statue in sight.

In early October the AME’s organ [the Christian Recorder] . . . reported the devastating news that “the monument is totally destroyed.” During the transport of the monument from Cincinnati to Philadelphia, while crossing a river in Pennsylvania’s Lehigh Valley, a railroad accident rendered the entire pedestal irreparably damaged--according to one report, lost overboard. But the monument was not, in fact, “totally destroyed.” Alfred White’s bust of Allen, which sat protected in a marble alcove, survived unharmed. Delayed yet again, and its overall configuration significantly altered, a monument to the AME Founding Father would finally make its long-heralded appearance at the Centennial.7

On 2 November, just eight days before the Exposition’s closing, a modestly attended dedication ceremony took place. The bust of Allen was mounted on a pedestal of granite blocks, one “much less elaborate” than the original. Adding insult to injury, the Centennial organizers ordained the statue’s removal from the site within sixty days of the Exposition’s closing.8

In 1877, the bust found a home, “probably in storage,” at Wilberforce University, a black institution established in 1856 by the AME in Xenia, Ohio. The bust’s presence at Wilberforce was verified by Mother Bethel’s pastor and an art historian and returned to Philadelphia in 2010.9

A solitary lithographic image that treats African Americans respectfully appears in Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the Centennial Exposition, 1876, which showcased some 800 illustrations contributed by prominent U.S. artists for the Centennial. The image depicts African American men, women, and children, all in fancy dress, at the statue called The Abolition of Slavery in the United States, or The Freed Slave, sculpted by Francesco Pezzicar.10

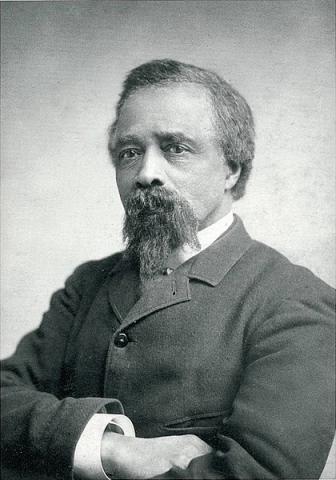

Respectful treatment was not accorded one of the Exposition’s major prize winners, the black painter Edward M. Bannister. Bannister’s submission won the Centennial gold medal, though not without controversy. As one source puts it, “the judges were flabbergasted” to learn that the award-winning painting “Under the Oaks” was the work of a black artist. When they tried to rescind the award, the other artists rallied to Bannister and threatened to leave the Exposition. Bannister retained his gold medal.11

American Indians

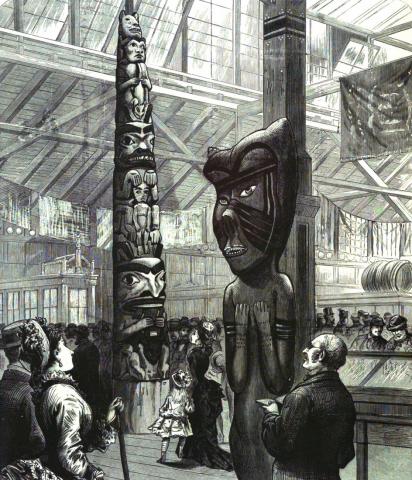

The Centennial Exposition’s Government Building was designed to exhibit “the functions and administrative faculties of the Government.”12 The Department of the Interior collaborated on its Indian exhibit with the Smithsonian Institution, which would inherit the artifacts on display and exhibit them in the soon-to-be-built Arts and Industries Building in Washington, DC (constructed in 1878, modeled on the Centennial’s Government Building). Spencer F. Baird, of the Smithsonian, was assigned to curate the display, which was not to include live Indians. “Special emphasis was placed on collecting objects that did not appear to be influenced by white contact,” though this proved to be difficult.13 “Ethnological researchers,” most with limited expertise, were hired by Baird to collect in the West, Pacific Northwest, and Alaska. Collect they did! “Practically every inch of floor space was covered with pottery, bean and wampum work, carvings, costumes, and domestic utensils, to name just a few of the objects displayed.” Ultimately, it was “an exhibit of curiosities,” reflecting the collection’s major weakness: the lack of connection between objects and cultures.14

One of the display’s novelties was its use of costumed “life-size papier mache figures,” most of which were dressed in warrior clothing and displayed holding primitive weapons. “Baird’s goal of attempting to enlighten the public about native cultures probably did not succeed largely because exhibit techniques were not sophisticated enough to deal with the general attitude that Indians were inferior and primitive beings.” In short, the collection reinforced popular stereotypes of native cultures.

Seeking to absolve federal Indian agents of their corrupt, neglectful treatment of reservation tribes, the pundit William Dean Howells declaimed in his commentary on the Centennial for the Atlantic Monthly (1876):

The red man, as he appears in effigy and in photograph in this collection, is a hideous demon, whose malign traits can hardly inspire any emotion softer than abhorrence. In blaming our Indian agents for malfeasance in office, perhaps we do not sufficiently account for the demoralizing influence of merely beholding these false and pitiless savage faces; moldy flour and corrupt beef must seem altogether too good for them.15

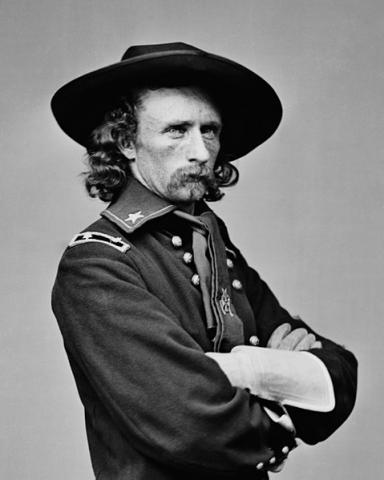

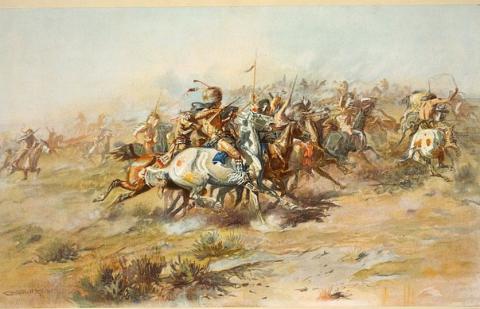

On 6 July 1876, shocking news from a sensationalist front-page report in the New York Times reached the Centennial that the notorious Indian fighter George Armstrong Custer and more than a third of his 7th Cavalry Regiment had been wiped out in their attack on a “hostile” Indian village camped on the Little Bighorn River in southern Montana. The timing of Custer’s demise on 25 June was ironic. “Golden boy,” hubristic Custer was certain of his coming victory in eliminating the last vestige of Indian resistance on the northern Plains. His glorious reputation as a peerless Indian fighter, he persuaded himself, would propel him to the presidency in 1878. The Centennial Exposition was to be a way station on that path. An account from 1896 has it that “all men knew that General Custer, if left to his own devices, would soon end the campaign one way or another. Custer and some of his officers were anxious to witness the opening of the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in July 1876.”16

It seems highly likely that “Custer’s Last Stand” reinforced the cultural stereotypes that the Centennial collection’s curator, Spencer Baird, had clumsily strived to alter in the public mind.

[1] Mary Frances Cordato, “Toward a New Century: Women and the Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition, 1876,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 107, no. 1 (1983): 114.

[2] Gary B. Nash, First City: Philadelphia and the Forging of Historical Memory (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 272.

[4] Cordato, “Toward a New Century,” 113–135, quotes from pp. 115, 118.

[5] Kathryn Kish Sklar, "Hull House in the 1890s: A Community of Women Reformers," Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 10, no. 4 (1985): 675-77; Mary Jo Deegan, Jane Addams and the Men of the Chicago School, 1892-1918 (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Press, 1988); Ellen Fitzpatrick, Endless Crusade: Women Social Scientists and Progressive Reform (New York: Oxford University Press, 1990).

[6] Mitch Kacun, “Before the Eyes of All Nations: African-American Identity and Historical Memory at the Centennial Exposition of 1876,” Pennsylvania History 65, no. 3 (1988): 300–323, quotes from pp. 305–306, 308–309.

[9] “Historic Bust of Richard Allen Returns to Phila.,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 June 2010.

[10] Frank H. Norton, ed., Frank Leslie’s Historical Register of the United States Centennial Exposition, 1876 (Philadelphia: Frank Leslie Publisher, 1877).

[11] New England Historical Society, “Edward Bannister Stuns the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition,” accessed from newenglandhistoricalsociety.com, 7 November 2019.

[12] Judy B. Zagras, “North American Indian Exhibit at the Centennial Exhibition (1976), 162, accessed from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/j.2151-6952.1976.tb00496.x, 8 November 2019.

[16] Nathaniel Philbrick, The Last Stand: Custer, Sitting Bull, and the Battle of the Little Bighorn (New York: Penguin, 2011), 350.