The Past as Present: The Evolving Cultural Landscape of West Fairmount Park

The past is present in the form of a 21st century cultural landscape that preserves elements of the 1876 Centennial Exposition.

Two of the Centennial Exposition's principal buildings were intended as permanent structures. Memorial Hall was extensively renovated after World War II, and today is home to the Please Touch Museum. The second building, Horticultural Hall, was demolished in 1955, after a long drought of neglect, with extensive hurricane damage administering the coup de grace.

The organizers of the Centennial Exposition and city authorities planned to leave two great buildings in place as permanent memorials to the great fair: Horticultural Hall and Memorial Hall. Yet post-1900 architectural trends would intersect with diminished city budgets in assigning a low priority for the maintenance of these buildings and, indeed, for the maintenance of the park terrain on which the Exposition stood. Several developments are worthy of consideration: the fates of Horticultural Hall and Memorial Hall, the retention of the Exposition’s statuary, and the construction of the Japanese teahouse and gardens on a lagoon near Belmont Avenue. We note in passing that aside from Memorial Hall, the only other building of any importance left standing is the smallish Ohio House, on Belmont Avenue.

Horticultural Hall

Evocative of a Moorish (Spanish Islamic) castle, ornate Horticultural Hall was built to be a permanent structure in West Fairmount Park and an enduring memorial to the 1876 Centennial Exposition. Yet that plan went badly awry. As early as 1910, “Horticultural Hall was . . . thought to be ‘in such bad condition that the Park Commission feared that it would collapse and injury [sic] many persons.’”

As the decades passed, observers reported a steady deterioration of the once venerable building, “a gray, friendly ghost of a fading age.” In 1953, the president of the Fairmount Park Commission put it this way: “Badly rusted framework holding heavy glass panes in the vaulted roof make it likely that the panes with come loose in the near future and fall to the floor. This condition is dangerous and we’d better do something about it before somebody gets hurt.”

While the Commission concluded that Horticultural Hall was probably destined for the wrecking ball, the coup de grace came a year later with the onslaught of Hurricane Hazel, the decade’s most destructive storm, which blew out the glass panes in the building’s roof. “We’re now faced with the problem of tearing it down or it falling down,” remarked one official. The wrecking ball arrived in 1955.1

Memorial Hall

After the Exposition’s closing, “the exhibits of 34 countries and a number of U.S. states” were shipped by rail to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., where they would be curated in the National Museum. As for Memorial Hall, the building reopened in the spring of 1877 as the Pennsylvania Museum and School of Industrial Art.

Beginning in 1928, Memorial Hall shared the city’s art collections with the new Philadelphia Museum of Art, which was built on the site of the former Fairmount reservoir, at the western end of Benjamin Franklin Parkway. Memorial Hall continued as a venue for small exhibits and storage of some collections “until 1956, when it was converted to a recreation center and headquarters for Philadelphia’s Fairmount Park Commission. In 1961, a basketball court was inserted in the west gallery, and locker rooms were built on the ground floor. In 1962, the east gallery was converted into an indoor swimming pool. By the 2000, the building’s deteriorating condition led the Park Commission to seek a new tenant to restore Memorial Hall. Please Touch Museum signed an 80-year lease on February 14, 2005.”2

Statuary

Some of the Centennial Exposition’s statues are still to be seen in West Fairmount Park. Flanking the entrance to Memorial Hall, two statues of the “Winged Pegasus” are probably the most recognizable to visitors. Lesser known, though highly visible, is the Total Abstinence Fountain at 52nd Street and Parkside Avenue, a western boundary marker of the former Exposition site, standing at the foot of George’s Hill and the Mann Center for Performing Arts. The fountain shows “Moses holding a tablet of the Ten Commandments towering over . . . [a collection of] 19th century [Catholic] luminaries.”3

A statue that was installed on the former fairgrounds in the Depression Era warrants a note here. It was the Colored Soldiers Memorial, installed in the late spring of 1934 on Landsdowne Drive east of Belmont Avenue–Fairmount Park (the former carriageway behind Memorial Hall). The Philadelphia Art Jury’s placement of this statue in a sparsely visited, far-flung corner of the park instead of a place of genuine honor on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway thwarted the sponsors’ intentions. The jury’s decision was consistent with the era’s racial prejudices against blacks. Sixty years would pass before this injustice was rectified: “In 1994, the All Wars Memorial to Colored Soldiers and Sailors was refurbished, rededicated and finally reinstalled—this time on Logan Circle—a place of prominence and respect.”4

Shofuso Japanese House and Garden

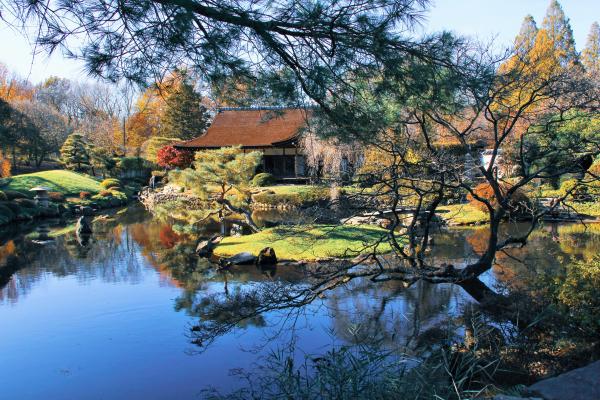

Shofuso, a splendid non-profit exhibit, features a “traditional 17th century-style house and garden” situated on a lagoon, once part of the Centennial Exposition located between Agricultural and Belmont avenues.

Built in 1953 and gifted to the U.S. as a symbol of postwar Japanese friendship, the house was displayed for several years in the courtyard of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York. In 1958, the house was transferred to its present site in West Fairmount Park; it was reconstructed in 1976 for Philadelphia’s Bicentennial celebration. The exhibit draws about 30,000 visitors each year.5

[1] Ken Finkel, “The Demise and Demolition of Horticultural Hall,” PhillyHistory Blog, PhillyHistory.org, 21 November 2017.

[2] Please Touch Museum, “History and Memorial Hall and the 1876 Centennial,” accessed from the museum’s website, 19 November, no longer available at URL researched on that date.

[3] Joan Springer Papa, “No One Throws a Party Like Philadelphia (Did), Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, 6 February 1972.

[4] Ken Finkel, “The Zigzag Drama of a Memorial Day Monument,” PhillyHistory Blog, PhillyHistory.org, 30 May 2016.