A History-Making Event in West Philadelphia

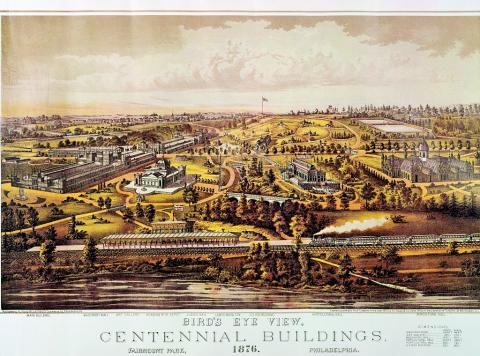

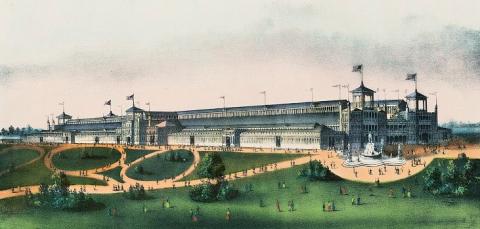

In 1876 national and international attention focused on West Philadelphia when West Fairmount Park hosted the Centennial Exposition. The Exposition, which celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence, was also the first world’s fair held in the United States.

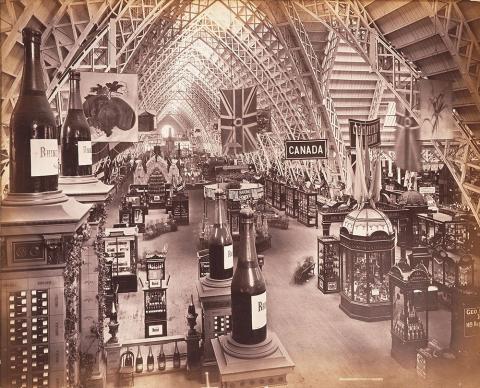

While the 1876 Centennial Exposition was organized as a world’s fair, the first on U.S. soil, it was explicitly planned to showcase America’s meteoric rise as a world industrial power. The Exposition showcased numerous breakthrough inventions, among them the telephone, typewriter, and sewing machine, and introduced novelties such as root beer, popcorn, and bananas to American consumers. Five main buildings dominated this cultural landscape and reflected the eclectic dynamism of the fair.

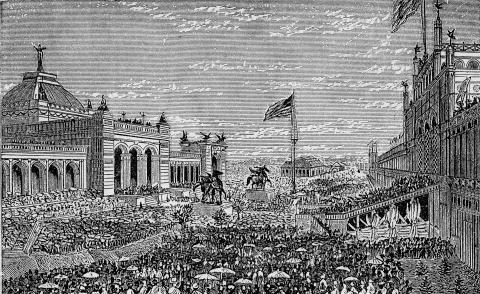

A throng of 180 thousand people packed the Exposition grounds on opening day, May 10th, with President Ulysses Grant presiding at the opening ceremonies. By the time the world’s fair closed six months later, about 10 million people had streamed through the 285 acres of the extensive fairgrounds, dazzled by displays of scientific and industrial innovation, world cultures, and the myriad buildings and landscaping of the grounds. The cost of admission? 50 cents, or $12.00 in 2019 dollars.

Among the 200 buildings and displays of 50 nations, some notable developments were:

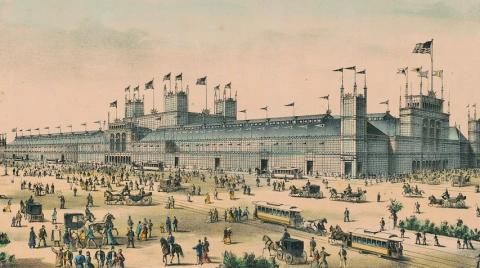

- The 35-acre Main Hall, the largest building ever constructed at the time, described by a contemporary observer as a “monster edifice” extending one-third of a mile in length.

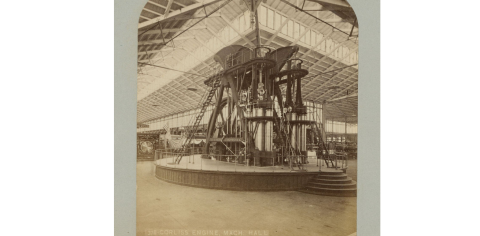

- The enormous Corliss Centennial Engine, a steam engine powering most of the Exposition’s buildings and exhibits.

- The first public demonstration of Alexander Graham Bell’s telephone.

- The hand and torch of the Statue of Liberty, the first part of the statue on display in the United States.

- The first model kindergarten.

- The introduction of root beer (Hires), popcorn, the band-aide, and the banana to U.S. audiences.

- Displays of typewriters and sewing machines, both new inventions.

Planning and Building the Centennial Exposition

In 1871, the U.S. Congress passed a bill authorizing the creation of the United States Centennial Commission, with the proviso that the federal government would not be responsible for funding the Exposition. Through a stock issuance and a subscription campaign of the Women’s Centennial Exhibition Committee1, $1.784 million was raised by 1873. The City of Philadelphia and the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania provided subsidies of $1.5 million and $1 million, respectively. In 1876 Congress (finally) approved an appropriation of $1.5 million. The fairgrounds, 236 acres of fenced-off land, were dedicated on 4 July 1873.2

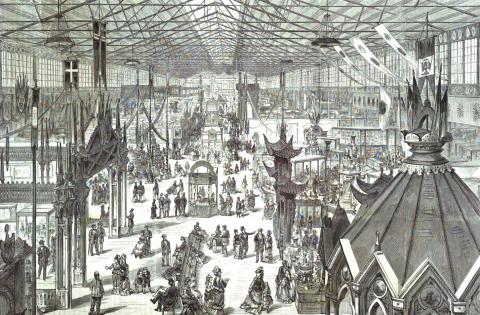

The Centennial opened on 10 May 1876. More than 100,000 people overflowed the Avenue of the Republic between Memorial and Main Hall to witness the opening ceremony, which was attended by numerous dignitaries, among them President U.S. Grant and the Brazilian emperor Dom Pedro II. A processional followed the president and emperor to the day’s next big event, the opening of Machinery Hall:

The President and Dom Pedro made their way to Machinery Hall, where they turned the handles activating the gigantic Corliss engine, a machine of huge flywheels and walking beams that powered the fourteen acres of machinery in the hall, fourteen acres of printing presses, spinning machines, sewing machines, and typecasting machines. A Lockwood envelope-making machine that was a favorite with Centennial crowds began to fold flat pieces of paper into envelope form; a pin machine, supervised by a little girl, began pounding pins into paper strips at the rate of five per second. Manufacturers of glue and curled hair displayed their wares. The American Screw Company exhibited three thousand screws. The Pennsylvania File Works displayed the world’s smallest file, measuring a half inch, and the largest, which measured six feet and was etched with pictures portraying the progress of American file making. There were car wheels and diamond saws, water pumps and locomotives. Surveying the puffing, humming, hammering spectacle of Machinery Hall, a reporter for the Atlantic wrote,” … Surely here, and not in literature, science, or art, is the true evidence of man’s creative power; here is Prometheus Unbound.”3

Not only were great inventions on display, but also “oddities,” creations that may offend 21st century moral and aesthetic sensibilities:

One popular exhibit was the head of Iolanthe, a classical heroine, sculpted by a Caroline S. Brooks—out of butter. In Agricultural Hall hung a liberty bell made from tobacco plugs and a Moorish chandelier with cigars for candles. The Kansas and Colorado Building contained a capitol dome built from apples. On the wall of the Iowa Building were two huge flowered wreaths made entirely from human hair. Proving that Americans weren’t alone in their enthusiasm for this kind of oddity, the government of Venezuela exhibited a picture of George Washington—made from the hair of Simon Bolivar. In a magnificent understatement Centennial judges commended the display for “originality of conception.”4

Twenty-one of the states represented at the Exposition constructed a house for administering the polity’s affairs. In its construction, Ohio House showcased and advertised that state’s sandstone quarries.

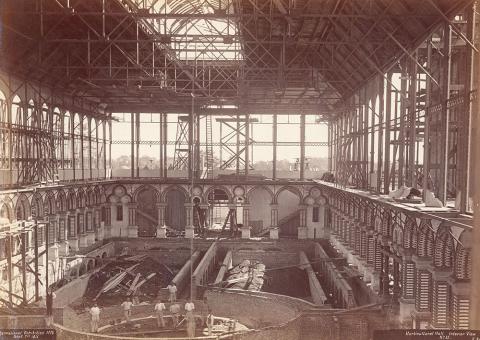

Main Exhibition Building (alternately, Main Hall), was the world’s largest building at the time, measuring 1,880 feet in length (more than a third of a mile) and 464 feet in width (more than 1 ½ football fields). U.S. and international products related to mining, metallurgy, manufacturing, education, and science.5

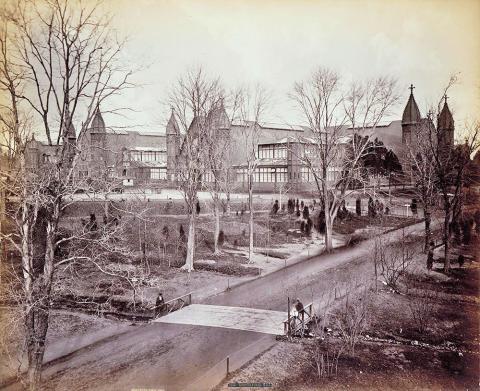

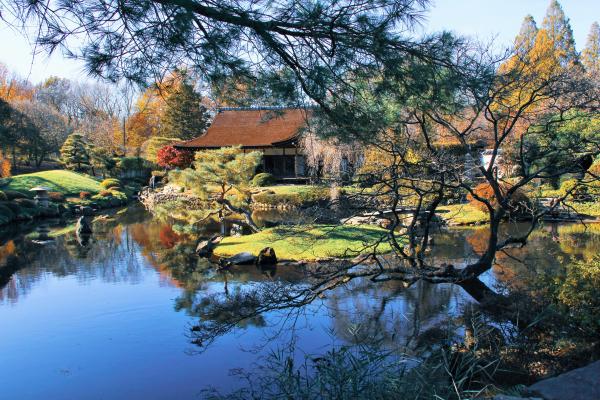

Memorial Hall housed the Centennial’s art gallery, which displayed “3,256 paintings and drawings, 627 works of sculpture, 431 works of applied art and nearly 3,000 groups of photographs from 20 nations.”6

Holding the art and architecture of the Exposition to a different aesthetic and moral standard than the one that prevailed in the post-Civil War era, critics such as Lewis Mumford (1930s) and Russell Lynes (1950s) viewed the event as “an architectural and cultural calamity” (Lynes’ phrase). There is no denying that the architectural styles on display in 1876 were eclectic, even chaotic, apropos of the dynamism of the Industrial Age. They were also adaptations of historical styles. The Centennial’s lead architect, the German immigrant Hermann Joseph Schwarzmann, looked abroad for his inspiration: “Nearly all the buildings referred to some historical style—Gothic, Renaissance, and even Islamic were popular choices—though the styles were seldom applied correctly according to academic standards.”7

Memorial Hall incorporated elements of a French Beaux Arts design and this building in turn inspired the design of the German Reichstag building in Berlin.8

Joseph Wilson and Henry Pettit designed Main Hall. Wilson and Pettit were architects and civil engineers who had done extensive work for the Pennsylvania Railroad. Though their proposal finished third in the competition to build Main Hall, the two frontrunners were eliminated when their designs proved too expensive to implement. Consequently, Wilson and Pettit got the contract. It was a wise selection. They completed the massive building (twelve times the size of Memorial Hall) ahead of schedule for less than a sixth of the cost estimate of the top-ranked design. Wilson and Petit also designed and built Machinery Hall.9

A 20-by-40-foot scale model of the Exposition was completed in 1889 and displayed at the Spring Garden Institute. Later the model’s creator, John Baird, donated it to the City of Philadelphia, which displayed it at City Hall from 1890-1894, then put it in storage. In 1902, the model was placed in the basement of Memorial Hall, where it has since reposed. At present, Please Touch Museum is redesigning the space surrounding the exhibit and equipping it with high tech digital tools that allow viewers to interact with it.10

[1] Gary B. Nash, First City: Philadelphia and the Forging of Historical Memory (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 272; Stephanie Graham Wolf, “Centennial Exhibition (1876),” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia.

[2] Dorothy Gondos Beers, “The Centennial City, 1865–1876,” in Philadelphia: A 300-Hundred Year History, ed. Russell F. Weigley (New York: Norton, 1982), 416–470.

[3] Lynne Cheyney, “1876: The Eagle Screams,” American Heritage 25, no. 3 (1974), accessed from http://www.americanheritage.com/1876-eagle-screams.

[5] “Centennial Exposition,” Wikipedia.

[6] Please Touch Museum, “History and Memorial Hall and the 1876 Centennial,” accessed from the museum’s website, 19 November, no longer available at URL researched on that date.

[7] Jeffrey Howe, “A ‘Monster Edifice’” Ambivalence, Appropriation, and the Forging of Cultural Identity at the Centennial Exposition,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography126, no. 4 (2002): 635–650.

[9] Douglas Ewbank, Powelton History Blog: A Collective Biography of a Philadelphia Neighborhood, https://poweltonhistoryblog.blogspot.com/p/about-powelton-village.html.

[10] Please Touch Museum, “History of Memorial Hall and the 1876 Centennial,”; “Time Traveling,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 November 2019.