Going National: Dick Clark and ABC's American Bandstand

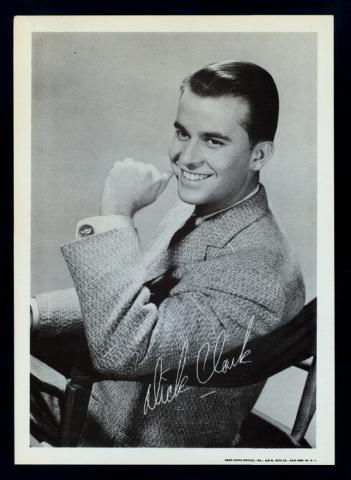

“Squeaky clean” commercial pitchman and deejay Dick Clark inherited Bob Horn’s locally broadcast Bandstand in July 1956 and revamped it for a national audience of teenage consumers as ABC’s American Bandstand, which first aired in August 1957.

In July 1956, Dick Clark, a commercial pitchman and deejay with an unsullied reputation, inherited WFIL-TV’s Bandstand from scandal-tainted Bob Horn and revamped it for a national audience of teenage consumers as ABC’s American Bandstand, which first aired in August 1957. Clark’s daily afternoon program pioneered in musical television by showcasing a range of black and white pop music performers, including R&B, rock ‘n’ roll, and country. Yet, as the third and fourth stories in this collection show, there was a downside to American Bandstand’s Philadelphia years.

Dick Clark Comes to Bandstand

At age 26, Dick Clark, a native of Westchester County, New York, and a 1951 graduate of Syracuse University, started out at WFIL-TV doing commercial spots. From 1954 to 1956, in addition to his television work pitching an array of products, he hosted Dick Clark’s Caravan of Music, a radio version of Bob Horn’s WFIL-TV Bandstand targeting an older audience than Horn’s “teeny-boppers.”

Horn’s firing from Bandstand in the spring of 1956 opened the door for the boyish-looking, telegenic Clark to be his successor the following summer. Overweight at age 40, Horn was neither boyish-looking nor telegenic, and, quite unlike Clark, he had a salacious reputation among his colleagues. (Regardless, kids liked Horn, and many were loyal to Horn.)

Dick Clark’s public persona was “squeaky clean,” “All American,” and “choir-boyish”—an image he assiduously cultivated. Clark recognized, especially as rock ‘n’ rock gained popularity among teenagers in the mid-1950s and was widely regarded by their distraught parents as a sign of moral collapse, that as a pitchman for the music that drove their kids to euphoric distraction, Clark would need parental trust. By the time Clark delivered a revamped Bandstand to national audiences as American Bandstand in 1957, the show was ostensibly squeaky clean.

Clark’s first day as Bandstand’s new host was 9 July 1956. The first order of business was to lure disaffected Horn loyalists to his version of Bandstand. For the most part—the future deejay, guru of “oldies” radio, and memoirist Jerry Blavat being a notable exception—he was able to do this. Horn had appointed a committee of 12 youngsters to monitor the behavior of their peers in the studio; Clark expanded the size of this committee and he enforced a code of conduct that required boys “to wear a suit jacket, shirt, and necktie”; prohibited girls from wearing “tight sweaters, low-necked dresses or pants”; and banned gum, smoking, and “obscene or profane language.” Lastly, “no one under age 14 or older than 18 [was] to be admitted.”1

The Rise of American Bandstand

Otherwise, Clark and his producer, Tony Mammarella, stayed with Horn’s formula of teens dancing to hit records in Studio B and showcasing the talents of lip-syncing musical guests. Such was Clark’s attractiveness to corporate sponsors and the appeal of Bandstand to teenage audiences in the nation’s third largest city that the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) saw an opportunity to market sponsors’ products to a national audience of teenage consumers valued at $9 billion.

American Bandstand first aired 5 August 1957 in the 3-4:30 afternoon slot. “Dick Clark introduced records, and the camera followed teenagers as they selected partners to dance,” writes historian Matthew Delmont. “Two or three times during the show, Clark would introduce singers or groups who would lip-sync their latest hits.”2

As America’s “only national deejay,” Clark wielded enormous influence that figured prominently in the meteoric rise of both white and black performers. A hallmark of early American Bandstand was Clark’s promotion of Italian-American male “teen idols,” sex-symbol pop singers who hailed from South Philadelphia: Frankie Avalon (née Francis Avallone), Bobby Rydell (née Ridarelli), and Fabian (née Fabiano Forte). An Italian-American teenager raised in Newark who achieved similar stardom appearing on American Bandstand was Concetta Franconero, whose stage name was Connie Francis, whose breakout hit was “Whose Sorry Now.”

Clark’s usual practice was not to play any record that was not already a hit in some major local markets; this applied to recordings by Avalon (“a nice little voice”), Rydell, and Francis.3 Fabian, who by all accounts was no singer, presented a different case: his “fabulous” looks drove teenage girls to gleeful screaming fits.

That was incentive enough for Clark and Chancellor Records engineers to figure out how to record Fabian’s voice and then manufacture it into a sound that would excite his audience. “I can hardly recognize my own voice,” said Fabian. But all he had to do was lip-sync and wiggle a bit and the screaming would start.

Once some decent songs were funneled through this process, notably “Turn Me Loose,” Fabulous Fabian was on his way to stardom. Former Bandstander Arlene Sullivan, famous in her own right as a Bandstand regular in the late 1950s, recalled, “There weren’t many people in the fifties who did not think that Fabian was the handsomest boy they’d ever seen. He was stunning. Beautiful, if you will.”4

Critics have derisively called the Fabian-Avalon-Rydell, white-teen-idol side of American Bandstand “Philadelphia Schlock,” also “tame rock and roll.” Yet, as the historian Matthew Delmont observes, there was an edgier side to Clark’s show, a side that “hosted R&B vocal groups like the Shirelles; rockabilly and country-influenced artists like Brenda Lee, Johnny Cash, Conway Twitty, and Patsy Cline; and Motown artists such as Mary Wells and Smoky Robinson and the Miracles; as well as R&B and soul pioneers like James Brown and the Famous Flames, Marvin Gaye, and Aretha Franklin. If American Bandstand helped push Philadelphia Schlock up the charts in this era, it also exposed viewers to a wider range of music than did Top 40 radio."5

A talented local pop group that dodged the label “Philadelphia Schlock” was Danny and the Juniors, four white teenagers who attended John Bartram High School in Southwest Philadelphia and who rose meteorically in Clark’s orbit with “At the Hop,” a catchy song to which Clark held half of the publishing rights. It became “one of the biggest rock ‘n’ roll records of all time.”6

Undoubtedly, one of Clark’s biggest coups was his promotion of Chubby Checker (née Ernest Evans), born in South Carolina and resettled in South Philadelphia, where he attended South Philadelphia High School. In 1960, Checker recorded “The Twist,” a song written and first recorded by Hank Ballard, an R&B pioneer.

In the summer of 1959, Ballard’s version of “The Twist,” described as an “underground phenomenon,” was being danced to by “torso-twisting, hip-thrusting” black teenagers. Recognizing the song’s potential, but also that the dance in the Ballard version, with its “very suggestive horizontal hip movement,” wasn’t appropriate for prudish national television. Clark had Checker simplify the dance step by toning down the hip movement. Checker himself “twisted” as he performed the song.

By 1961, “The Twist” and Checker’s follow-up record, “Let’s Twist Again (Like We Did Last Summer),” were an international phenomenon. While the Chubby Checker craze lastly only a few years, the singer is credited with transforming pop music dance from the jitterbug rock ‘n’ rock style to an “open dancing format,” which, unlike the jitterbug, didn’t require a partner.7

American Bandstand was by no means Dick Clark’s only entrepreneurial venture. Among the many projects in Clark’s musical portfolio was ABC’s Saturday night version of American Bandstand. The Dick Clark Show was broadcast live from ABC’s Little Theater in Manhattan.

The sponsor was Beechnut Foods, for whom Clark pitched Beechnut Spearmint Gum and, contrary to the “no gum” rule on his daily Philadelphia show, Clark encouraged his New York audience to chew and chew again, the more visible the chewing the better. And Clark’s aides distributed “IFIC” (“it’s flavor-ific!”) Beechnut buttons to be worn by “the masticating young audience.” The Dick Clark Show aired weekly from February 1958 to September 1960, when ABC terminated the program in the wake of a payola (bribery/kickback) scandal in the pop music industry.8

[1] Larry Lehmer, Bandstandland: How Dancing Teenagers Took Over America and Dick Clark Took Over Rock & Roll (Mechanicsburg, PA: Sunberry Press), 55. For more information on Dick Clark’s rise, see John A. Jackson, American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), chap. 3.

[2] Matthew F. Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock ‘n’ Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 142.

[3] Ibid., 147; Jackson, American Bandstand, 30-31, 99-101, 107, 145-47; Lehmer, Bandstandland, 74-75.

[4] Jackson, American Bandstand, 137-39, 145-46; “The Diary of Arlene Sullivan,” in Arlene Sullivan, Ray Smith, and Sharon Sultan Cutler, Bandstand Diaries: The Philadelphia Years, 1956-1963 (Chicago: Coney Island Press, 2016), 59-60.

[5] Delmont, Nicest Kids in Town, 148.