Whose Music, Whose Dances? Whose Culture? Race and American Bandstand

Black music and black dances originating in Philadelphia neighborhoods contributed substantially to the success of American Bandstand; yet American Bandstand’s dancefloor and bleachers were racially segregated, and some of the show’s most popular dances were adapted without attribution from black neighborhoods.

The longstanding popular belief about American Bandstand, promoted by Dick Clark in the later years of his career, is that the Philadelphia version of the show racially integrated the Studio B dancefloor and bleachers. That belief is persuasively challenged by recent scholarship: American Bandstand “The Philadelphia Way” not only excluded black teens from the show but also represented black dances as having originated on the show with its white dancers. Consequently, black teens were in effect erased from the national youth culture that formed around American Bandstand.

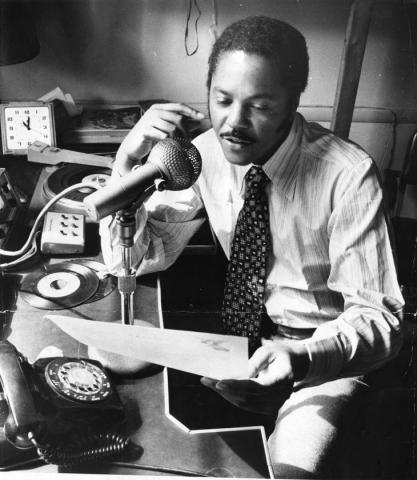

Dick Clark’s American Bandstand owed a formidable debt to two black Philadelphia-area deejays: Georgie Woods, a pop music promoter and civil rights activist, and Mitch Thomas, the producer and host of The Mitch Thomas Show.

Georgie Woods was Philadelphia’s leading black radio and record-hop deejay, whose employer was WDAV. Woods produced rock and roll concerts on behalf of the National Association of Colored People’s (NCAA’s) Legal Defense and Education Fund. Ever the social activist, Woods viewed his concerts, which attracted as many as 30,000 teenagers, as deterrents to juvenile delinquency.

Mitch Thomas worked in both radio and local television, and like Woods, he hosted record hops at skating rinks and recreation centers. The Mitch Thomas Showwas broadcast weekly across the Philadelphia region from WPFH in Wilmington, DE. In its design, American Bandstand would look a lot like The Mitch Thomas Show, with teenagers dancing to rock and roll records and musical guests lip-syncing their latest hits. The difference? Here the deejay was black, and the audience was black. Also, WPFH had no national network affiliation.

What did Woods and Thomas contribute to the development and popularity of American Bandstand? Plenty says the historian Matthew Delmont: “Rock and roll developed in Philadelphia thanks largely to Woods, Thomas, and their teenage audiences. Dick Clark tapped into this excitement for rock and roll, first as a radio deejay, and after as the host of American Bandstand. Clark acknowledged that Woods’s and Thomas’s programs influenced the music and dance styles on his show.”

White dancers on American Bandstand transferred dances from Thomas’s show to Clark’s national audience.1 (As we will later see, for their part, the white Bandstand dancers failed to credit their black counterparts as creators of the steps that they modified and represented as their own.)

Yes, the dancers on American Bandstand were white teenagers. Having combed through myriad “archival materials, newspaper accounts, video and photographic evidence and the memories of people who were regulars on American Bandstand or who were excluded from the show,” Delmont concludes that Dick Clark’s claim in later life “that the show’s studio audience was fully integrated by the late 1950s” was (wittingly or unwittingly) a distortion of reality.2

The practice of segregating American Bandstand’s audience and dancefloor was rooted in the show’s predecessor program, Bob Horn’s Bandstand. The original Bandstand began on an integrated “first-come, first-served basis” (1952-53), though Horn’s orientation toward mainstream pop music and its white performers was off-putting (“corny music”) to young blacks. As Bandstand gained in regional popularity and attracted regional sponsors who targeted teenage white consumers, Horn excluded blacks from Bandstand.3

Dick Clark continued Bandstand’s practice of segregation and extended it to American Bandstand. There is no denying that Clark, to his credit, opened his show’s stage to black R&B and rock ‘n’ roll performers, showcased their hit records, and contributed to their careers. At the same time, Clark, with ABC’s backing, catered to the racial prejudices of American Bandstand’s corporate sponsors, who worried about white parents’ association of sex and race with rock ‘n’ roll; more precisely, the sponsors feared that white and black bodies dancing together, or even in proximity, would conjure white parents’ paranoia about miscegenation.

American Bandstand fostered the creation of a national youth culture. The show was an advertising juggernaut focused on teen consumers, showing white kids on camera consuming products like 7-Up and Dick Clark Bandstand Shoes. What acne-prone white kid didn’t dab on Clearasil, a perennial Bandstand sponsor, as a nightly ritual? As Delmont argues, this orchestration of the tastes of white teenagers marginalized black youth:

Teenagers tuned into American Bandstand to watch other teenagers dance to records, to see musical artists perform, and to try out the latest dance moves in their own living rooms. American Bandstand’s daily images encouraged teenagers to imagine themselves as part of a national audience enjoying the same music and dances at the same time . . . Many of the show’s regular dancers and local fans hailed from working-class Italian-American neighborhoods, and they later remembered American Bandstand as providing them with unique exposure . . . [Yet] the program’s racially discriminatory admissions policies remained in place. With the program broadcasting nationally, black teens were erased not just from the “WFIL-adelphia” regional market, but also from the national youth culture American Bandstand worked to build.4

The American Bandstand regular Arlene Sullivan, a rowhouse-dwelling working-class girl from Southwest Philadelphia, achieved national teen adulation as a regular dancer on the show. In her frank and poignant memoir of her time on the show and her life after Bandstand, Sullivan unambiguously states, “There were no blacks on Bandstand, even though the studio was in a mixed neighborhood.”5 Examining thousands of Bandstand images, Matthew Delmont found only two images of blacks (two girls in each photo) in the bleachers.6

How was the exclusion of blacks orchestrated? Given the city’s anti-discrimination policies, this required some shenanigans on the producers’ part. “The show’s producers denied they had a white-only policy, but the black teenagers who tried to get into the studio were always excluded for some reason,” explains Delmont. “Some were told that they lacked a membership card, others that they did not meet the dress code, and others that the studio was full.”7

As for the origins of the dances that American Bandstand’swhite dancers introduced to the nation’s teens, the music historian John A. Jackson writes:

Although the show’s core of white dancers introduced new steps on TV that they had purportedly devised, by and large those steps originated in Philadelphia’s black communities. What Bandstand, and later American Bandstand, actually did was to act as a filter to make those black dances acceptable to white society. . . . American Bandstand regulars did pass off black-inspired dances as their own creations. In doing so, most of them did not think they were stealing from their black counterparts. “But we were,” said Joe Fusco, a regular dancer on Clark’s show who admitted that it “wasn’t fair, really, when you think about it,” that whites received all the credit for originating the dances featured onAmerican Bandstand.8

Viewed in hindsight, the great irony of American Bandstand “The Philadelphia Way” was Clark’s promotion of rising black R&B and rock and roll stars at the same time that he and his producers segregated the Bandstand dancefloor and bleachers. Once Clark moved American Bandstand to California, the growing strength of the Civil Rights Movement in the mid-1960s compelled ABC to integrate the program’s audience and dancefloor.

[1] Matthew F. Delmont, The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock ‘n’ Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in 1950s Philadelphia (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

[2] Matthew Delmont, “Remembering Dick Clark, Forgetting the Segregation of American Bandstand,” Washington Post, 22 April 2012.

[3] Delmont, Nicest Kids in Town, 43-45.

[5] “The Diary of Arlene Sullivan,” in Arlene Sullivan, Ray Smith, and Sharon Sultan Cutler, Bandstand Diaries: The Philadelphia Years, 1956-1963 (Chicago: Coney Island Press, 2016, 51-52.

[6] Delmont, Nicest Kids in Town, 186-87.

[7] Ibid., 186. Delmont provides a telling quote from Clark, statement from 2003: “[W]hen we integrated the studio audience in the early days, we were truly going where no television show had gone before. Black kids and white kids would not only be sitting together in the bleachers, but out on the same floor dancing. We weren’t even sure what the reaction would be in our conservative hometown, Philadelphia, much less on ABC affiliates through the Deep South. Perhaps because we didn’t boast about what we were doing, or announce it, or talk about it in any way--we just did it--it went virtually unnoticed” (p. 161).

[8] John A. Jackson, American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 208, 209.