Starting Local: WFIL-TV, Bob Horn, and Philadelphia's Bandstand

The program that preceded Dick Clark’s American Bandstand at WFIL-TV was deejay Bob Horn’s locally popular Bandstand.

Dick Clark’s American Bandstand was the offspring of deejay Bob Horn’s Bandstand, which WFIL-TV broadcast daily from 1952-56 from a WFIL studio at 4548 Market St. The program’s signature features were Philadelphia teens dancing to popular music and the portly Horn interviewing musical guests who lip-synced their latest hits on the show. When Horn’s personal indiscretions led to his ouster from Bandstand in 1956, he was replaced by the more youthful, slimmer, “squeaky clean” Dick Clark.

This history of Dick Clark’s nationally televised American Bandstand begins with a short-lived radio program called Bandstand, which was introduced in 1951 by the deejay Bob Hornat WFIL Radio in Philadelphia. The story of the radio program that became the local television program Bandstand, which became American Bandstand, is sketched as follows:

In 1945 the communications mogul Walter Annenberg purchased WFIL, an affiliate of the American Broadcasting Company (ABC) that was housed in Center City. WFIL was a property of Annenberg’s Triangle Productions Inc., which counted Seventeen Magazine and the Philadelphia Inquirer among its numerous media ventures.(Annenberg would soon launch TV Guide.)

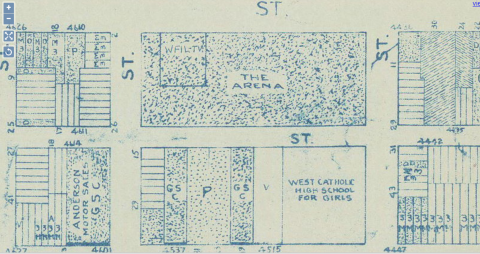

In 1947, Annenberg created WFIL-TV and hired Roger Clipp to direct WFIL’s radio and TV operations. In 1952, the City Center radio facilities were relocated to share studio space with WFIL-TV in a “warehouse-type structure” at 46th and Market streets. The “beige brick” building, which stood in the shadow of the Market Street Elevated (rising from the subway tunnel at the 45th St. portal), was located next door to the Philadelphia Arena.

Impressed by the popularity of 950 Club, a locally televised program broadcast by WPEN Philadelphia, WFIL’s Roger Clipp decided to take a chance on having Bob Horn (age 46, described by one historian as “carrying a few too many pounds . . . look[ing] more like a used car salesman than a teenager’s Svengali”1) transfer his radio version of Bandstand to television. Produced by Tony Mammarella, with Horn and Lee Steward as co-hosts, Bandstand debuted on 13 October 1952. As of Spring 1953, the time-slotwas 2:45 to 4:45 daily.

Bandstand featured teens dancing to the records of white “crooners” like Frankie Laine, Tony Bennett, Perry Como, and South Philly native Eddie Fisher; visits by musical guests who lip-synced their recent hits; Horn’s interviews with these guests (announced by Horn’s signature shout, “We’ve got company!”), lots of commercials targeting youthful consumers; and a Rate-A-Record feature. Bandstand proved to be wildly popular in the Philadelphia region, boasting a membership of 10,000 adolescents. As only 200 could fit in the cramped studio at any one time, the program operated in half-hour rotations through the afternoon. Teenagers lined up outside the studio before showtime in seemingly interminable numbers. Between 1952 and 1955, Bandstand counted over 250,000 teenagers in Studio B. Horn had proved his point that kids liked watching other kids dance.2

Two lily-white Catholic high schools located near WFIL were the major feeders for Bandstand: West Catholic High School for Girls, and West Catholic High School for Boys. (See the third story in this collection for more on the whiteness of Bandstand and its successor program, American Bandstand.)

Bandstand’s home was the building’s 3,100-square-foot Studio B. The studio was expressly designed to be a “teeny-bopper” venue.

A canvas backdrop painted to resemble the interior of a record store was resurrected . . . and the name Bandstand was added to a faux window. Pennants of local high schools were attached to curtains flanking the stage and a lectern resembling a store counter was built, with space in front to list the top 10 tunes of the week. Collapsible bleachers were installed on one side of the studio, giving it the appearance of a high school gymnasium.3

In 1955, WFIL dropped Lee Steward as Horn’s co-host, much to Horn’s relief, as Horn deeply resented having to share his show with a co-host. Ironically, within the next two years, Horn would find himself in disgrace and ousted from Studio B.

Horn’s troubles at WFIL stemmed from his alcoholism and alleged predatory sexual behavior. In June 1956, WFIL’s station manager ordered Horn’s banishment in the immediate wake of the Horn’s DWI arrest and, more seriously, rumors circulating about his sexual involvement with an underaged girl who frequented Bandstand.

Horn was indicted when the girlfiled a criminal complaintand was bound over for trial in Philadelphia. After a mistrial and subsequent retrial, Horn was acquitted on the basis of prosecutor’s technical error in the pretrial pleadings. But his reputation and career were in tatters. In 1958, the erratic Horn was convicted on yet another DWI charge, this time spending three months behind bars. In the wake of that embarrassment, he was convicted and fined for federal income tax evasion.4

Bob Horn, for all his character flaws, was a transitional figure in rock and roll history. He and his producer Tony Mammarella created Bandstand for the Philadelphia region. The slimmer, more youthful, “squeaky clean” deejay Dick Clark would inherit the program and Horn’s role as deejay host and adapt both for a national audience.

Around 1953, Horn’s Bandstand started playing R&B records though these were cross-over-covers by white performers. It was a small step toward the music revolution that American youth in the late 1950s would be swept up in. The time when black R&B and rock ‘n’ rollartists would lip-sync their own music and be interviewed before a national television audience was soon to come. That prospect takes us to American Bandstand “The Philadelphia Way."5

[1] John A. Jackson, American Bandstand: Dick Clark and the Making of a Rock ‘n’ Roll Empire (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 16.

[2] For Bob Horn’s Bandstand, see Jackson, American Bandstand, chap. 2; Larry Lehmer, Bandstandland: How Dancing Teenagers and Dick Clark Took Over Rock & Roll (Mechanicsburg, PA: Sunbury Press (2019), chaps. 2–3.

[3] Lehmer, Bandstandland, 12.

[4] See ibid., chap. 9 for details on Horn’s legal troubles.

[5] In his authoritative book The Nicest Kids in Town: American Bandstand, Rock ‘n’ Roll, and the Struggle for Civil Rights in the 1950s (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), the historian Matthew F. Delmont provides a well-researched, provocative analysis of race relations in Philadelphia’s version of American Bandstand. For more on Delmont’s findings, see the article in this collection titled “Whose Music, Whose Dances, Whose Culture? Race and American Bandstand.”