Lovely Abattoir on the Schuylkill: The Railroad and the Stock-Yard Company

The Pennsylvania Railroad built a centralized 21-acre slaughterhouse complex on the west bank of the Schuylkill that operated from approximately 1877 to 1925.

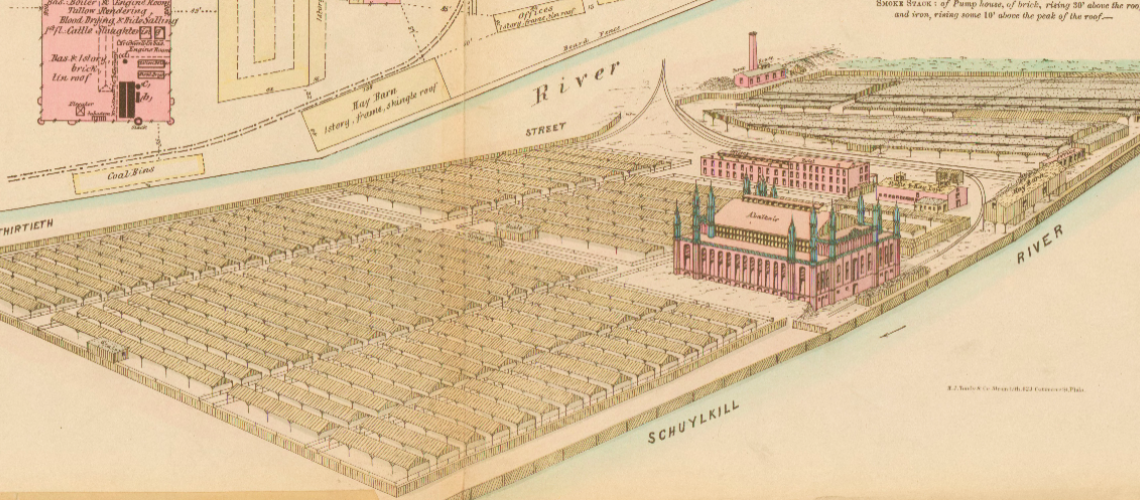

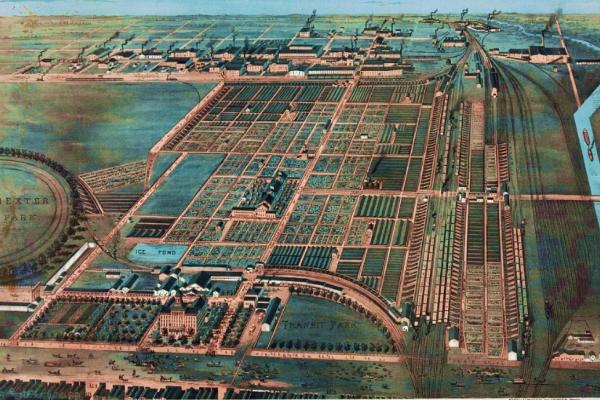

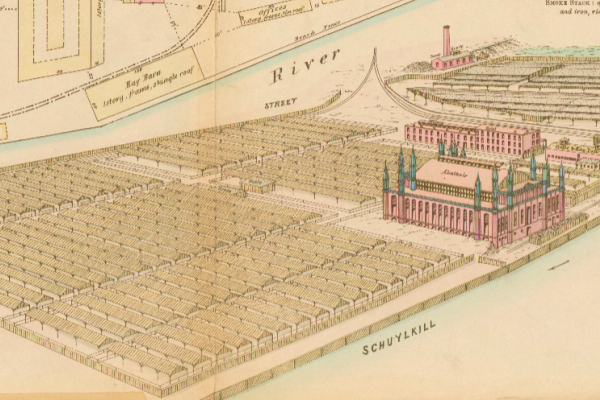

From the mid-1870s to the mid-1920s, the Philadelphia Stock-Yard Co., under the auspices of the Pennsylvania Railroad, operated a 21-acre centralized slaughterhouse complex on the west bank of the Schuylkill, located to the immediate north of 30th & Market St. The complex included pens for cattle, hogs, and sheep, a colorful abattoir, and administrative offices.

The 21-acre Philadelphia Stockyards, constructed on the west bank of the Schuylkill River by the Pennsylvania Railroad, was Philadelphia’s version of Chicago’s 475-acre Union Stock Yards, the bellwether and flagship operation of the nation’s highly competitive post-Civil War meatpacking industry. At the West Philadelphia site, massive numbers of cattle, pigs, and sheep were collected and slaughtered in a mechanized and cost-efficient central location and dressed for sale in East Coast markets.1

The first notice of the Philadelphia Stock-Yard Co., which would operate the Philadelphia Stockyards on land owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad (PRR), appears in the early spring of 1872, when the City authorized the company to erect temporary wooden sheds for housing cattle, presumably on the PRR’s property above the Schuylkill north of Market St.2 The railroad was briskly moving forward with its plan for the stockyards in the fall of 1874. Some objections were raised by individuals and groups hostile to the plan, citing concerns about river pollution, the latter receiving the loudest objections. For example, one incensed letter writer, initials B.S., registered the following colorful fulmination:

What of the blood and entrails, and bones covered by portions of tissue, and the tons of fat they propose to render on the premises, and the raw hides and the liquid and solid excrement of the cattle—will there be no necessity for washing the floors and pavements after the manipulation of all this animal matter, and where, but into the basin of the Schuylkill will their drainage flow, where it will be held and deposited with the mud at the bottom and accumulate after the feeble ebb tide along and around the wharves, bridge piers, and the banks of the river. The mixture of deposited animal matter with the mud of the river-bottom would form a compound mass horrible to contemplate and permanent in its nature. Nothing would obliterate it but a convulsion of nature.3

Of far greater political import was a “Letter from a Committee of Citizens to the Pennsylvania Railroad—Their Views on the Proposed Drove Yard and Abattoir,” signed by sixteen prominent Philadelphians. While the committee acknowledged that a centralized stockyards would be a considerable improvement on the then-prevailing decentralized chaos of small slaughterhouse operations scattered here, there, and yonder, the members cited problems with an existing stockyard facility in New Jersey operated under the PRR’s auspices and serving New York City. The committee forecasted that the problems in New Jersey would be greatly magnified in West Philadelphia if the railroad’s plan was implemented. Their primary concern was foul odors emitted by penned animals.4

The Philadelphia Stockyards complex was operational by 1877. By 1885, the 21-acre site housed cattle pens for 7,300 head, sheep pens for 10,000, hog pens of similar capacity as the sheep pens, covered sheds for about 500 cows and calves, the “main office and exchange building,” stables for holding and selling horses, the abattoir, and the “fat and reducing department."5

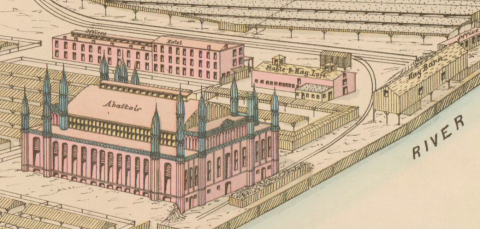

In their 1885 catalogue, Wilson Bros. and Co., the architectural firm that designed the abattoir, disavowed any environmental problems with odors or waste disposal, describing the business of the abattoir thusly:

The work of slaughtering the cattle is carried on entirely on the main floor, the portion devoted to this purpose being divided off into pens, the floors of which are laid with heavy pine planking carefully caulked. The cattle are admitted by doors in the end of the building, through which they pass into the middle aisle, and thence by gates into the slaughtering-pens, the centre space being fenced off from the sides by iron- pipe railings. Each pen is provided with the requisite apparatus for slaughtering, and with appliances for hanging up the carcasses and dressed meat. The blood and refuse are removed to that part of the building devoted to their utilization, and an ample supply of hot and cold water is provided. The building is warmed by steam. The abattoir has a capacity for killing and dressing 1200 head of cattle daily.

The catalogue’s description asserts, “[T]he business of the abattoir is carried on, practically in the heart of a large city, without being in any way offensive. Every part of the animals slaughtered is utilized, and none of the refuse is allowed to pass into the river.” The description gives no indication as to the disposal of contaminated water, whose apparent drainage site is the river.6

Were malodors emanating from the animal pens a problem for residential neighbors? In his history of Pittsburgh’s East Liberty Stock Yards, David Rotenstein cites a complaint registered by Mr. R.S. Robertson, a stockyards neighbor, in a Pennsylvania court in 1875. “I am acquainted with the situation of the East Liberty Stock-yards,” he said. “The smells arising from them were so exceedingly offensive that we were obliged to close the windows of my house and to burn camphor all over the house."7

The residential neighborhood nearest the Philadelphia Stockyards was Powelton, whose southern boundary was roughly a half-mile to the northwest. Regarding the question of a potential neighborhood nuisance, it is important to consider that Powelton was home to many employees of the Pennsylvania Railroad in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both the top bosses and general employees.

Here are several examples. PRR president William Hasell Wilson lived at 3501 Powelton Ave. from 1867 until his death in 1902. The railroad’s second vice president, Charles Edmund Pugh, resided at Baring St. addresses, according to the 1870 and 1880 U.S. Census; Pugh oversaw the handling of the more than three million passengers who attended the 1876 Centennial Exhibition via the 32nd St. Station. John Wilson (of Wilson Bros. & Co., architects of the abattoir) lived at 302 N. 35 St. from 1878 until his death in 1896. Down the ranks, John McNeil, a locomotive engineer, resided on N. 31st St. from 1867 until his death in 1901; conductor William Hayes is listed at 3102 Hamilton St. in the 1880 U.S. Census, Isaac Van Houten, superintendent of car shops, at 3205 Race St., from 1867 to 1899. Simply put, there seem to have been no ill-winds blowing foul smells across Powelton in the decades the Philadelphia Stockyards was operational.8

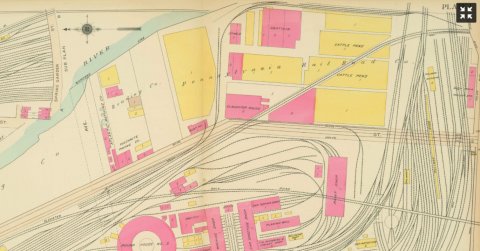

Blogger Mark Dominus provides a logical explanation of one apparent quirk that appears on the early survey and insurance maps that depict the Philadelphia Stockyards—the “hotel” that adjoins the stockyards offices. Dominus suggests that “the perplexing ‘hotel’ is not intended for humans. ‘Hotel’ is apparently stockyard jargon for a place where livestock are quartered temporarily just prior to slaughter.”9 (The 1916 Bromley map shows a different configuration of buildings on the same site as the earlier Offices/Hotel building, one of which is labored “Slaughterhouse”; see Related Media)

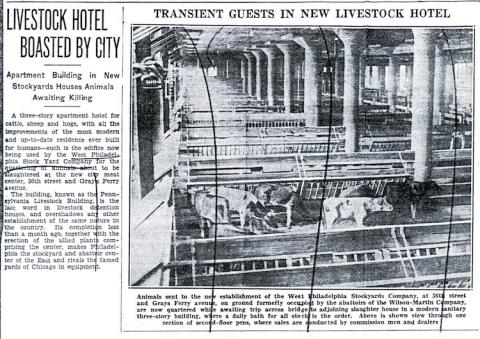

The Philadelphia Stockyards operated for nearly fifty years. By the early 1920s, the Pennsylvania Railroad had its eye on the future. Between 1920 and 1925, the 21-acre site was cleared to make way for building the PRR’s 30th Street Station between 1928 and 1933. Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania (today Amtrak) Station funneled freight and passenger traffic up and down the East Coast and east-west across Pennsylvania. As for the Philadelphia Stockyards, in 1931 its slaughterhouse operations reopened in state-of-the-art facilities in the area of Gray’s Ferry Ave. & 36th St. (an area that is today home to Penn’s Pennovation Center); the property was previously owned by the Wilson-Martin Co., a slaughterhouse merger discussed in the next article in this collection.10

1. David Rotenstein, “Slaughterhouses on the Schuylkill,” accessed from https://blog.historian4hire.net/2015/09/22/slaughterhouses-on-the-schuyl... , 5 September 2020.

2. “Philadelphia City Government,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 12 April 1872.

3. “Special Notices,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 October 1874.

4. “Abattoirs,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 25 November 1874.

5. Wilson Bros. and Co., Catalogue of Works Executed (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott, 1885), 55–56, posted in Rotenstein, “Slaughterhouses on the Schuylkill.”

7. David S. Rotenstein, “Model for the Nation: Sale, Slaughter, and Processing at the East Liberty Stock Yards,” Western Pennsylvania History, winter 2010–11, p. 37.

8. Analyses provided to author by Douglas Ewbank, emeritus research professor and demographer, University of Pennsylvania Sociology Department, August 2020.

9. Mark Dominus, “Philadelphia Slaughterhouse Hotel—Universe of Discourse,” 2 July 2019, accessed from https://blog.plover.com/history/slaughterhouse-hotel.html, 5 September 2020.

10. See clipping from Philadelphia Public Ledger, 29 June 1931, posted in Rotenstein, “Slaughterhouses on the Schuylkill.”