This photo shows the wrought-iron fence with its marble and inlaid-brick globe columns that marked the eastern boundary of the Philadelphia General Hospital, today facing Civic Center Boulevard/Ronald G. Perelman Way. The fence, which extends for several city blocks, is the only surviving remnant of the sprawling institution that once stood on this site, spanning the years 1834–1977, serving first as the City’s almshouse for indigent poor, next as the City’s only public hospital.

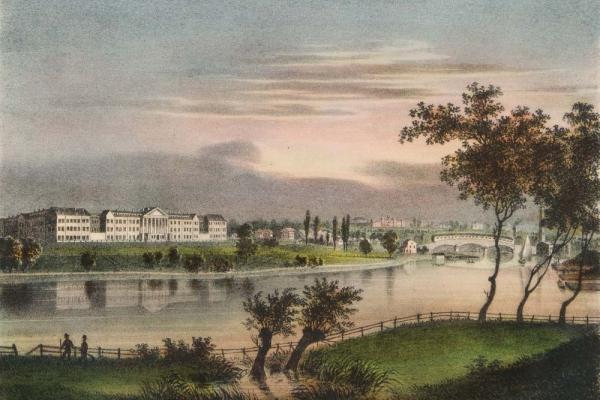

From 1834 to 1977, Philadelphia maintained its public hospital on the west bank of the Schuylkill River. The facility evolved from being a multipurpose almshouse to its single role as a full-service hospital.

In 1834, the City relocated its almshouse (poorhouse) to to the west bank of the Schuylkill River in Blockley Township, where it erected a swath of buildings for a public hospital, indigent housing, a workhouse, and an insane asylum. In 1902, the Blockley Almshouse was officially renamed the Philadelphia General Hospital. Divested of its almshouse role and insane asylum at the time of the First World War, PGH grew in the following decades to become one of the nation’s renowned public hospitals. Following the Second World War, at the high point of the Great Migration, the City’s poor African Americans, especially African American women, made PGH their hospital of choice.

Stories in this Collection

In 1834, the City relocated its almshouse (poorhouse) from 11th and Spruce streets in the central city to a 187-acre tract of farmland in Blockley Township in West Philadelphia. Located on hilly terrain above the Schuylkill River, the Bockley Almshouse, by 1854, provided free indigent services in four sprawling brick-and-stone buildings that housed indigent residences, workshops, and hospital facilities, including an insane asylum. If its critics are to be believed, the almshouse evolved as a “dismal place” from the 1850s to the eve of the First World War. |

Two transfers of Blockley Almshouse property by the City to the University of Pennsylvania, the first in 1870, allowed the University to relocate its small central-City campus to West Philadelphia. College Hall, the first building on the site, opened in 1872, followed in 1874 by the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania. In 1882, a second transfer of almshouse property gave Penn the land on which it would build the Museum of Archeology and Anthropology and Franklin Field, among other historic structures. |

At the turn of the twentieth century, anti-black race-writers provided perverse justifications for denying essential social and health services to African Americans in segregated northern cities. Statisticians such as Frederick Hoffman interpreted indicators they found in the 1890 Census as conclusive evidence that African Americans were a diseased and dying population group—hence their recommendations to policy makers to deny essential social and health services to this population. Hoffman and others like him foisted their own racist assumptions onto their data and ignored social conditions born of racial isolation and discrimination that spawned the indicators they badly misinterpreted. |

In 1902, the Blockley Almshouse was officially renamed the General Hospital of Philadelphia (PGH). Transferring its almshouse services and its “lunatic asylum” to public institutions in the northeast section of the City, PGH focused on clinical and surgical services, which were apparently deficient until two progressive mayors in the 1950s took charge, overseeing a change in the City’s charter that allowed them to funnel significant resources into the hospital, which became the hospital of choice for the City’s African American population. |

In 1977, the City, under Mayor Frank Rizzo, closed PGH, claiming it was no longer affordable. A consortium called the PGH Development Corporation, which included Penn, Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP), Seashore House, and the Veteran’s Hospital eventually gained control of the site, named it the Philadelphia Center for Healthcare Sciences, and put up seven medical research and treatment buildings between 1988 and the Millennium. In a parallel development, Penn and CHOP acquired the City’s Civic Center properties on Civic Center Boulevard opposite the former PGH site and put up avant-garde clinical and medical research facilities, and a parking garage. In combination, the Philadelphia Center for Healthcare Sciences and the Penn/CHOP expansions have created a veritable City of healthcare sciences in West Philadelphia. |