Blockley Almshouse

In 1834, Philadelphia relocated its almshouse (poorhouse) to Blockley Township in West Philadelphia, to a hilltop environ above the Schuylkill River; by 1854 the site included a swath of new buildings for indigent housing, workshops, and hospital facilities, including an insane asylum.

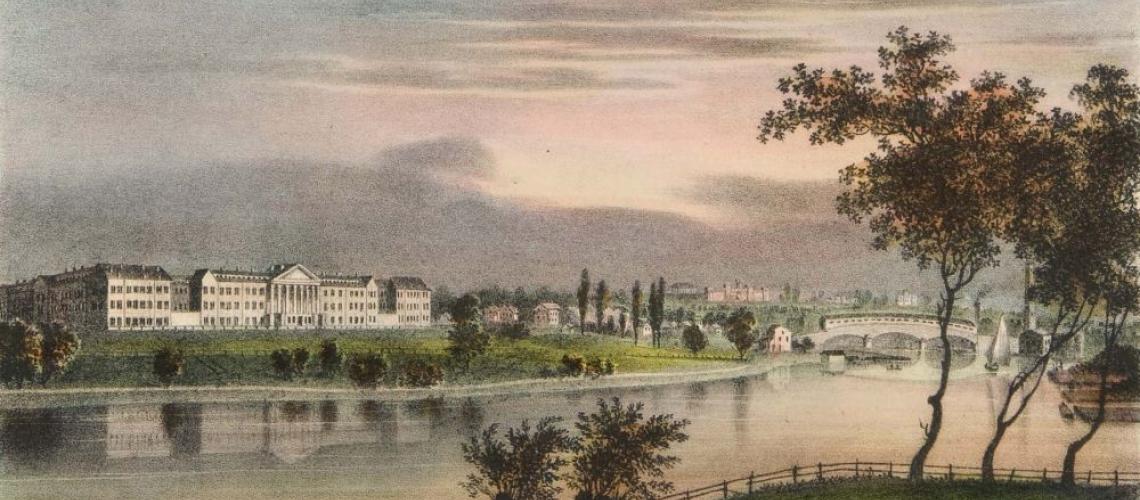

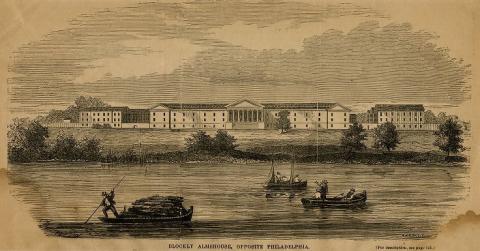

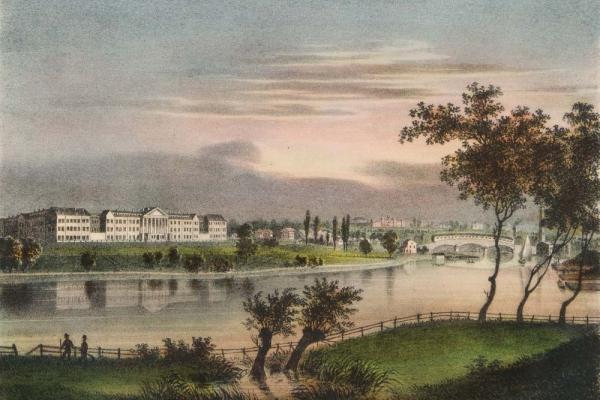

In 1834, the City relocated its almshouse (poorhouse) from 11th and Spruce streets in the central city to a 187-acre tract of farmland in Blockley Township in West Philadelphia. Located on hilly terrain above the Schuylkill River, the Bockley Almshouse, by 1854, provided free indigent services in four sprawling brick-and-stone buildings that housed indigent residences, workshops, and hospital facilities, including an insane asylum. If its critics are to be believed, the almshouse evolved as a “dismal place” from the 1850s to the eve of the First World War.

In 1834, the City relocated its almshouse (poorhouse) from 11th and Spruce streets in the central city to a 187-acre tract of farmland purchased in 1829 from the William Hamilton Estate in Blockley Township in West Philadelphia, hence the name Blockley Almshouse. By 1854, the year of Philadelphia City-County consolidation, a quadrangle of four sprawling brick-and-stone buildings surrounded by “a high board fence” stood on hilly terrain above the Schuylkill River, a short distance from the Woodlands Cemetery on the old Hamilton property. The almshouse included indigent housing, workshops, and hospital facilities with an “insane department.”[1]

In 1854, “the vicinity of the almshouse was distinctly rural. West Philadelphia was sparsely settled. The old Market Street bridge on the site of the more ancient ferry was the chief means of getting across the Schuylkill to the almshouse and hospital, although there was some ferriage from the east side to a wharf or landing on the almshouse grounds. Here and there near the almshouse farm were a few buildings for private business or public purposes, and a few wharves were located on both sides of the river.” The tracks and trestle of the Philadelphia and West Chester Railroad crossed the meadows of the bottomland on Blockley Almshouse property the City had transferred to the railroad.[2] (From the late-nineteenth to the twenty-first century, the University of Pennsylvania’s eastward campus expansion beyond Franklin Field toward the river would have to go under or over intractable railway lines.)

“Old Blockley” is properly viewed, in both its organization and administration, as one of several new and dramatic types of social innovations that appeared in the North in the 1830s and 1840s (precursors of twenty-first-century institutions). The decades at the midpoint of the National Period saw religious and moral impulses associated with the Second Great [Religious] Awakening shaping social reform. Religiously inspired members of the newly formed Whig Party and other reformers who shared their ideals created new institutions intended to provide custodial care for indigents and other castoffs from the nation’s new and transformative industrial economy. The sociologist David Labaree argues that the reformers’ primary aim was conversion; their primary instrument for accomplishing this aim was education. Labaree writes: “The penitentiary [an example would be Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary] was supposed to be a place for the inmate to become penitent, develop new work habits, and then return to society as a self-regulating and productive participant. The hospital and asylum [an example would be the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane in West Philadelphia] were supposed to rehabilitate patients and prepare them to take on responsibilities as citizens, family members, and workers. The poorhouse took care of the elderly who were unable to take care of themselves, but it also sought to retrain the younger and more able inmates in order to reintroduce them into the labor force. Every correctional officer, nurse, and attendant in these institutions was considered a kind of teacher.[3]

An ideal of social reform was one thing; implementing the reform to align with the ideal was quite another. One influential critic implied that the task was hopeless. “[T]he renowned” Dr. J. Chalmers Da Costa, at one time Blockley’s physician-in-chief, called Blockley “a microcosm of the City”: “Within these gray walls we find all sorts of physical and mental diseases, and also a multitude of those social maladies that degrade manhood, undermine national strength and threaten civilization itself. Here is drunkenness; here is pauperism; here is illegitimacy; here is madness; here are the eternal priestesses of prostitution who sacrifice for the sins of man; here is crime in all its protean aspects, and here is vice in all its monstrous forms.”[4]

Leon Rosenthal, who sketched a history of the almshouse in 1963, cited Da Costa and added his own measure of reproach: “Around the buildings of this dismal place was a high board fence with but one entrance on Darby Road. In 1875 it consisted of four three-story buildings 500 feet long, in which were housed 3000 inmates, 200 of whom were orphans, and 600 insane. In the region of Franklin Field was Blockley’s Potter’s Field where so many of the unhappy victims of this pesthole were buried. When 33rd Street was cut through to Spruce many skeletons of these unfortunates were unearthed.”[5]

If Da Costa, Rosenthal, and President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal advisor Rexford Tugwell, a 1917 graduate of Penn who recalled Blockley as an enormous and shamefully crowded “insane asylum” and a “gloomy pile,”[6] are to be believed, Blockley was a nightmare worthy of a Charles Dickens novel. Fortunately for the City, and poor African Americans who formed the cadres of the Great Migration that settled in Philadelphia between 1940 and 1970, the Philadelphia General Hospital, Blockley’s official name since 1902, was transformed to become one of the nation’s best public hospitals.

[1] John Welsh Croskey, compiler, History of Blockley: A History of the Philadelphia General Hospital from Its Inception, 1731–1928 (Philadelphia: F.A. Davis, 1929).

[3] David F. Labaree, Someone Has to Fail: The Zero-Sum Game of Public Schooling (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press), 52–79, quote from p. 63. Labaree suggests that the Common School Movement in the antebellum North and Midwest provided a model for Whig and Whig-like reformers working in other venues of social innovation.

[4] Quoted in Leon S. Rosenthal, A History of Philadelphia’s University City (Philadelphia: West Philadelphia Corporation, 1963), unpaginated, section on Blockley accessed from http://www.uchs.net/Rosenthal/rosenthalofc.htlm.

[5] Ibid. A contributor to Croskey, History of Blockley, described the remains as “many skulls and other ghastly osseous reminders.”

[6] Rexford G. Tugwell, To the Lesser Heights of Morningside: A Memoir (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1982), 10–11, 13.