Transforming “Old Blockley”: The Philadelphia General Hospital

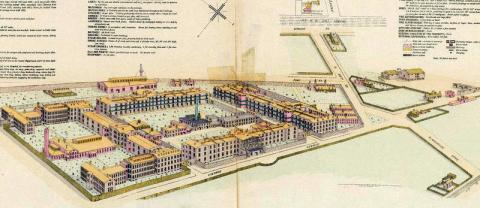

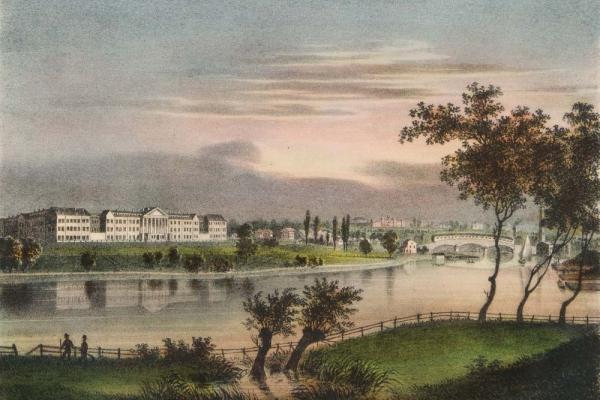

In the first half of the twentieth century, the Blockley Almshouse farmed out its almshouse services and its “lunatic asylum” and recast itself as the Philadelphia General Hospital, whose clinical services significantly improve after the Second World War.

In 1902, the Blockley Almshouse was officially renamed the General Hospital of Philadelphia (PGH). Transferring its almshouse services and its “lunatic asylum” to public institutions in the northeast section of the City, PGH focused on clinical and surgical services, which were apparently deficient until two progressive mayors in the 1950s took charge, overseeing a change in the City’s charter that allowed them to funnel significant resources into the hospital, which became the hospital of choice for the City’s African American population.

In 1902, the Blockley Almshouse was officially renamed the Philadelphia General Hospital. Before the First World War, its almshouse services for the indigent poor and its “lunatic asylum” were transferred to public institutions in the City’s northeast section.[1] “PGH began to focus exclusively on providing health care,” writes the historian Lisa Levinstein. “In addition to City employees and other special cases, PGH only admitted medically indigent patients, treating one-third of all patients in the City who could not afford to pay for their care.”[2]

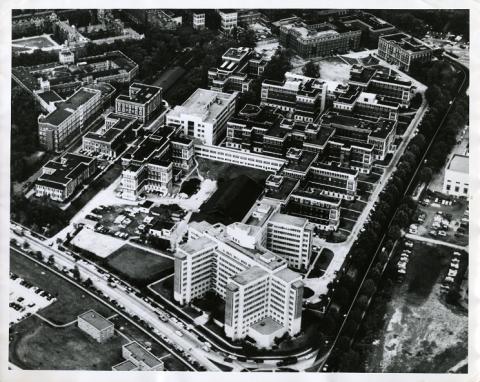

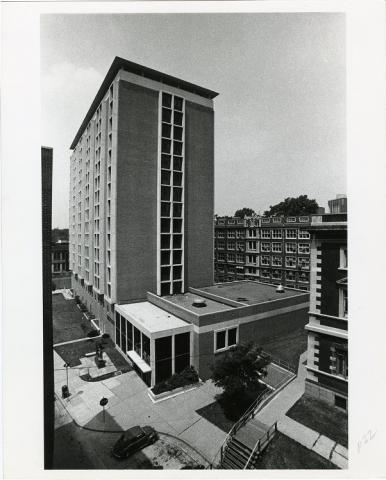

The years of greatest significance in PGH’s history were the three postwar decades, when the Great Migration of African Americans from South peaked (ca. 1950) and then concluded (ca. 1970). Improvements in PGH’s services, which began in the 1940s, increased significantly in the 1950s and 1960s with the reform-minded Democratic mayoralties of Joseph Clark Jr. (1952–56) and Richardson Dilworth (1956–62), who assigned a high priority to PGH. “Under their administrations,” notes Levenstein, “the hospital hired more staff, provided day care for employees’ children, and opened a new neurological building, tuberculosis ward, food service building, laboratory department, X-ray department, and operating suite. Outpatient visits soared after the construction of a new building with a much larger capacity and a range of new clinics.” Dilworth-era PGH attracted “world class doctors” who in turn attracted talented medical and nursing students. This array of healthcare professionals provided, as a general-rule, high-quality, respectful treatment to poor African American women, who were the hospital’s largest group of patients. For every four whites who chose PGH as their hospital, thirty-five African Americans made it their choice. More than 71 percent of the latter were women. As Levenstein notes, “gender-specific health concerns such as childbirth, injuries from illegal abortions, gynecological problems, domestic abuse, and rape” brought these women to PGH; they accounted for 94 percent of PGH’s births.[3]

While their services undoubtedly improved healthcare provision to poor African Americans, the problems the PGH doctors, nurses, and medical interns treated were symptomatic of malign environmental conditions they could not treat—conditions that in one form or another could be traced to racial discrimination and These well-documented conditions included residential segregation enforced by anti-black housing policies such as redlining and exclusionary zoning ordinances; unemployment and denial of access to job networks that were controlled by white labor unions; segregated education that resulted from school district policies that located new schools in residentially segregated neighborhoods, gerrymandered school catchment areas to maximize the separation of black and white students, and deprived majority-minority schools of educational resources; federal, state, and municipal policies that favored significant investment in Center City and disinvestment in “the neighborhoods”—priorities that included urban renewal incentives and generous tax concessions to “higher eds and meds,” especially the City’s largest private employer, the University of Pennsylvania.[4] The cruel irony was that policy makers and thought-leaders, much like the race-writers of a bygone century, attributed the conditions they observed in these poor neighborhoods to a culture they described as “a tangle of pathology.”[5]

Improved healthcare, says Levenson, did not always mean equitable treatment, despite the mandate in the 1951 City charter that “required the public hospital to enforce a clear, non-discrimination policy”: “While white staff members described PGH as a nonracist institution, many black patients . . . did not believe that the public hospital was free from racism.” While Levenstein musters some examples of disrespect and neglectful treatment on the part of the hospital’s physicians, her evidence suggests strongly that PGH was a far greater benefit than a liability for these women. For example, unmarried pregnant women seeking PGH obstetrical care were not “subjected . . . to intrusive and judgmental questioning and reprimands,” which was not the case at many of the City’s other hospitals. As another example, African American women who chose PGH entered a venue that facilitated social bonding within and across generations: “As African Americans, women repeatedly sought care at PGH and recommended the hospital to their family and friends, they created a strong sense of community at the hospital . . . a culture at the hospital that made it feel more like a vital part of the black community than like some of the alien or indifferent white-dominated institutions in the City.”[6]

The hard living experienced by impoverished African American women necessitated major adjustments on the hospital’s part. Premature births—linked to poor nutrition, pre-natal cigarette and alcohol use, problems with sanitation, and high levels of stress—was “the most widespread” problem in the late 1950s. Responding to the crisis, PGH opened a high-tech premature nursery, which it expanded within a few years, and a new pediatrics clinic. Another serious, more horrific problem was “the thousands of women arriving at PGH . . . with severe complications from illegal abortions. They ranged from young teenagers to women in their forties, and many had risked their lives when they or other women had tried to induce abortions by beating their bellies with boards or inserting sharp objects such as knitting needles, bicycle spokes, umbrella spokes, and coat hangers through their cervixes and into their uteruses.” While there is no denying that “some individual PGH doctors and nurses may not have upheld the policies mandating respectful treatment” in illegal abortion cases, Levenstein concludes that “PGH’s institutional commitment provided women with a unique opportunity to receive humane care.”[7] In many respects, PGH was a progressive “black hospital”—the preferred hospital for the City’s African American residents.

[1] Croskey, History of Blockley.

[2] Lisa Levenstein, A Movement without Marches: African American Women and the Politics of Poverty in Postwar Philadelphia (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 161. The renaming date as 1902 is noted in Donna Gentile O’Donnell, “The Closure of Philadelphia General Hospital: An Historical Analysis of Public Policy, Politics, and Healthcare Delivery” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of Pennsylvania, 2004), 23. O’Donnell’s monograph includes a history of Blockley/PGH; she gives particular attention to two notables of the late nineteenth century: Alice Fisher, for her advances in professionalizing nursing; and William Osler, for his advances in medical science.

[4] For policies and trends that spawned residential segregation, see Carolyn Adams et al., Philadelphia Neighborhoods: Division and Conflict in a Postindustrial City (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1999), esp. 17 (table 1.3), 31; James Wolfinger, Philadelphia Divided: Race and Politics in the City of Brotherly Love (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007), 11–35, 179–80, 191–202. For discrimination in labor markets, see Matthew J. Countryman, Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), 48–58; Guian A. McKee, The Problem of Jobs: Liberalism, Race, and Deindustrialization in Philadelphia (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008), 41–82, 115–16, 132. For national contexts of discriminatory housing, zoning, and employment policies and practices, see Richard Rothstein, the Color of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (New York: Liveright, 2017), chaps. 2–8. For segregated schools, see Michael Clapper, “School Design, Site Selection, and the Political Geography of Race in Postwar Philadelphia,” Journal of Planning History 5, no. 3 (2006). For city planning and investment priorities, see Gregory L. Heller, Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Philadelphia (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013); John L. Puckett and Mark Frazier Lloyd, Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015).

[5] Derrick Darby and John L. Rury, The Color of Mind: Why the Origins of the Achievement Gap Matter for Justice (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2018), chap. 5.