The Past Recaptured: Honoring the Memory of the Black Bottom

Spirited academically based community service projects of the late 1990s at University City High School honored the memory of the Black Bottom.

In the late 1990s, two service-learning projects, the planning for which originated in Penn’s Graduate School of Fine Arts (GSFA) and the School of Arts & Sciences, formed spirited collaborations between Penn undergraduates and University City High School (UCHS) students. Both partnerships honored the memory of the Black Bottom. The 1999 course taught by Andrea Zemel, of GSFA, created the Black Bottom Mosaic Mural. That same year, Billy Yalowitz taught a Theater Arts course that brought together UCHS students, Penn undergrads, and community elders to create Black Bottom Sketches and Taking a Stand, exuberant plays marked by great spontaneity, with performances in several community venues.

“Gatekeepers” and the Black Bottom Mosaic Mural

In the spring semester of 1998, Andrea Zemel, a mosaic artist (among her other talents) and lecturer in Penn’s Graduate School of Fine Arts (now Weitzman School of Design) taught a Netter Center-affiliated academically based community service course titled “Community, Collaborative, and Public Art” (FNAR 349). As their class project, Zemel’s enrolled undergraduates collaborated with two teachers and a team of UCHS students to design and install two sculptures that would symbolize a gateway (hence the project’s name “Gatekeepers”) between the two institutions. After a thorough scouting of possible locations and considerable discussion, the UCHS and Penn students chose to locate the sculptures on a path leading from the school’s main entrance on 36th Street to the northwest corner of 36th & Filbert Street. Zemel writes, “Set into six-foot reinforced concrete bases tiled with mosaic, one side held an open book bearing the epithet ‘Knowledge is Power’ and the other a single striving hand. Students made rough models out of graph paper, cardboard, and hardware cloth and then divided into small groups to oversee specific tasks of fabrication.”1

Zemel describes the engagement of the teams in practical studio work, as well as her own role as instructor:

Studio practice developed as an outcome of the project. As instructor, I demonstrated a variety of construction techniques, including tilemaking, glazing, welding, and shaping forms with hardware cloth. Ben [Penn], Kerwyn [UCHS] and Oriste [UCHS] consulted with Penn’s woodshop technician to determine the optimal method for constructing pour-forms for the concrete bases. Kira [Penn], Tali [Penn], Anisha [UCHS], Stacy [UCHS], and Markita [UCHS] focused on developing the surface design and creating tiles. Devon [Penn] worked with me to weld the book and the hand understructures. In pairing up with the UCHS students, the undergraduates took on mentoring roles. Likewise, in keeping with the notion of shifting roles and responsibilities, artistic and technical demands led me to assume more the part of resident artist than traditional university instructor.2

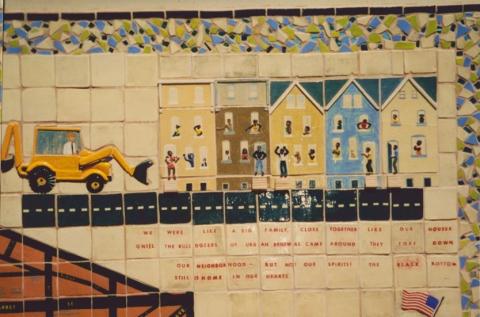

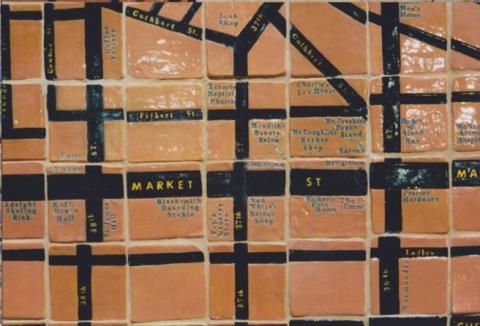

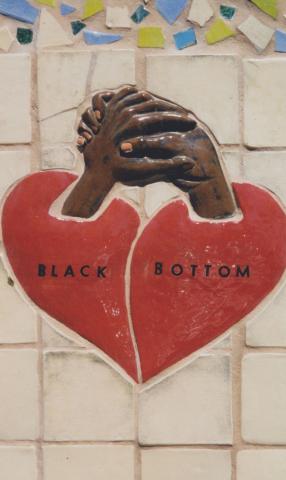

The following year, the spring semester of 1999, Zemel’s version of her course and her students’ collaboration with UCHS produced the “Black Bottom Memorial Wall,” a mosaic mural of the Black Bottom that would stand for 15 years outside the high school’s main entrance on 36th Street. Her syllabus for that year’s FNAR/URBS 349 described the primary goal of the course and the process of planning and constructing the memorial:

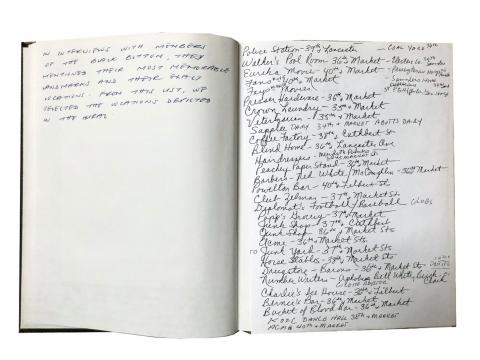

A significant portion of the course will involve developing our site at University City High School, located at 36th & Filbert Streets, just north of Market Street. Last year, the class completed Gatekeepers, two large-scale exterior sculptures located by the school’s main entrance. Part of this year’s course will use oral history materials collected on the Black Bottom, the site’s neighborhood prior to urban redevelopment. This information was compiled by [the Arts & Sciences course] Theater 1: Community Performance in West Philadelphia taught by Billy Yalowitz. [See “The Black Bottom Performance Project” below.]

Planning for the site project will involve input from Penn faculty and undergraduates, high school students, faculty, and administrators, as well as Black Bottom community members.

Fabrication for the project will involve intensive studio activity and on-site installation. Studio processes may include basic site rendering, ceramic tile installation, masonry techniques and other sculpture processes as required.3

The Penn students documented their participation and learning through “visual journals.” An important feature of their collaborative work was the participation of their high school counterparts in every stage of creating the mosaic mural. The scheduled date for completing the glazing of the fired ceramic tiles was 19 April, with the memorial’s installation scheduled to begin that day and to be completed by 3 May. The course syllabus included attendance at Black Bottom Sketches, a version of Billy Yalowitz’s Black Bottom Performance Project, performed at Penn’s Annenberg Center. The final paper for the course was to be a process description and critique combined with the visual journal and photo documentation. 4

In her heartfelt dedication speech, Zemel acknowledged the people who made the Black Bottom Memorial Wall a reality. They included students from UCHS who “came to our studio building diligently to make and glaze tiles: Monica Coleman, Latisha Dukes, Elaine Hall, Anthony Horton, Raheem Johnson, Yhazsminda Jones, Charisse Matthews, Latoya Monk, Latoya Patterson, Nafeesh Ziyach.” She also acknowledged “Principal Florence Johnson and Teacher Clare Tracy-Stichney.” And she thanked “Penn students who led the activities: Afia Ohene Frempong, Martene Sinclair, Kate Levitt, ceramic assistant Helen Cahng and student teacher Rachel Skerritt. And of course, the Black Bottom Elders who told us their story: John Wilson, Stanley Edwards, Hal Fergeson and Walter Palmer.” For their support, she expressed her gratitude to the Center for Community Partnerships (now Netter Center) and Kellogg Grant.5

NOTE: We take up the fate of the Black Bottom Mosaic Mural and the high school’s sculpted columns in “Once a High School,” the next article in this collection.

The Black Bottom Performance Project

Another highlight of the Lytle era was the Bottom Performance Project, which created and produced a play that memorialized and celebrated the Black Bottom. The project was directed by Billy Yalowitz, a social activist and adjunct professor in theater arts and dance who taught an undergraduate theater arts course at Penn in the spring of 1998 on “Community Performance in West Philadelphia,” in conjunction with Penn’s Center for Community Partnerships. Preparatory to his spring class, Yalowitz had spent the previous fall learning Black Bottom history and the backstory of Unit 3, and coordinating with the social activists Walter Palmer and Dr. Pearl Simpson to meet former residents of the Black Bottom.6 The project was designed to inspire creative energy, pride of place, and a sense of school and neighborhood community in UCHS’s African American students—and give respectful voice to former Black Bottom residents and their descendants. This experimental play, which was assisted by Yalowitz’s Penn students and featured UCHS students and Black Bottomers as performers, was staged in different formats tailored to particular audiences—UCHS’s auditorium, the Metropolitan Baptist Church in the West Powelton neighborhood, the Annenberg Center’s Harold Prince Theater, and the WHYY public television studio. Yalowitz describes the exuberant West Powelton performance:

In April 1998, a forty-person cast comprising Penn students, UCHS students and teachers, and Black Bottom community member performed Black Bottom Sketches at the local Metropolitan Baptist Church, which many Black Bottomers remembered as the site of teenage dances and socials. We designed the piece as a kind of living installation, an adaptation of the Black Bottom Valentine Cabaret [an annual social event], sitting, visiting, and “performing” with people seated banquet style in a large fellowship hall. We began that performance by having people introduce themselves to one another at the tables where we’d appointed a “storyteller” from the Black Bottom to host the invited guests from Penn and the high school. Each table functioned as a kind of storytelling circle, as between scenes we stopped the action so guests could ask Black Bottomers about the events and characters portrayed.

Around the space were five video monitors on which were shown home movies gathered from Black Bottomers, which interspersed the scenes and live music created by professional musicians, most of them from the Black Bottom. The standing-room-only audience included Black Bottomers and their children and grandchildren, high school students, parents and teachers, along with a smaller group of students, faculty, and administrators from Penn. It was an exuberant community event, marked by inspired improvised additions to the written script by the performers and enthusiastic outbursts of recognition and support by the audience. At one point, during a missed cue, Black Bottom Association President “Pest” Wilson took things into his own hands: he signaled the lighting board operator to turn the lights down low and the band to play a slow dance number and called an old friend up to dance. Their duet, doing the neighborhood dance called the “Slow Drag,” was met with cheers and whistles.7

Yet Yalowitz’s aspiration that the 1998 performance project would become an annual event, improved upon by more research and increased professionalism, was not to be realized after Torch Lytle’s departure.

1. Andrea Zemel, “Fine Arts 349: Community, Collaborative, and Public Art,” Art Journal 58, no. 1 (1999): 65.

3. Andrea Zemel, “FNAR/URBS 349: Community, Collaborative, and Public Art,” University of Pennsylvania Graduate School of Fine Arts, 1999. Zemel shared her syllabus with the author, 7 July 2021.

4. Zemel shared one of the visual journals with the author, 7 July 2021. The booklet contains student notes, drawings, and photographs. One set of photograph shows two UCHS students glazing fired ceramic tiles.

5. Andrea Zemel, “Text from the Dedication Ceremony for the Black Bottom Mural, May 1999,” shared with author, 26 June 2021.

6. Zemel, “FNAR/URBS 349” (1999).

7. Billy Yalowitz, “The Black Bottom: Making Community-Based Performance in West Philadelphia,” in Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World, eds. Bill Adair, Benjamin Filene, and Laura Koloski (Philadelphia: Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, 2016), 162–163. See also “Profile of Billy Yalowitz,” in White Men Challenging Racism, eds. Cooper Thompson, Emmett Schaeffer, & Harry Bond (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2003), reprint accessed from http://nuernbergcounseling.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/White_Men_Challenging_Racism.pdf, 17 June 2021; “The Drama of the Black Bottom, Residents Lift Voices Anew,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 22 April 1999.