The University City Science Center and the Black Bottom

Postwar urban renewal built the University City Science Center and forced the dispossession of working class and working poor African American residents in West Philadelphia’s Black Bottom. For nearly 60 years, resentment over the Black Bottom removals has targeted the University of Pennsylvania as the power broker in the decisions that led to the creation of the Science Center.

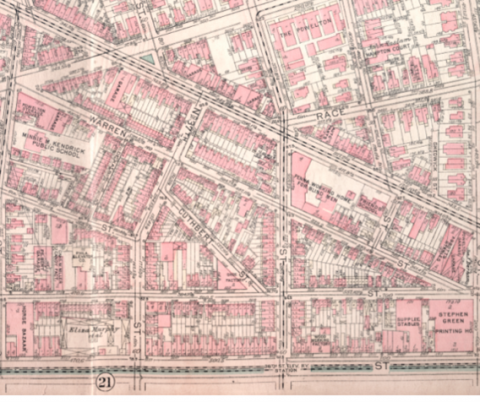

Today, the Market Street corridor between 34th & 38th streets is dominated by buildings of the University City Science Center, the nation’s first and largest urban research park. Since its incorporation in 1963, the Science Center’s story is part of the larger history of postwar urban renewal. It was the centerpiece of “Unit 3,” an urban renewal zone that was roughly coterminous with the largely working poor African American neighborhood known as the Black Bottom. The displacement of the Black Bottom’s residents paved the way for building the Science Center and University City High School, which was originally planned as a high school of science & technology. The University of Pennsylvania’s role in the Black Bottom removals and planning the Science Center has been a subject of heated controversy for the past 60 years.

Backstory of the University City Science Center

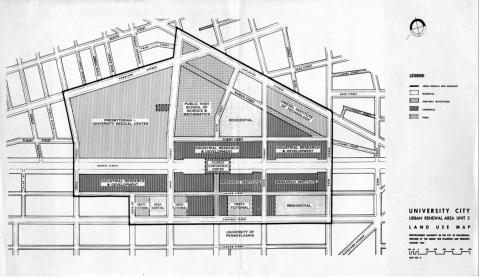

Today, the Market Street corridor between 34th & 38th streets is dominated by buildings of the University City Science Center (UCSC), the nation’s first and largest urban research park. Since its incorporation in 1963, the Science Center has been part of the larger history of postwar urban renewal. It was the centerpiece of “Unit 3,” an urban renewal zone established by the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority (RDA) that extended from Lancaster & Powelton avenues south to Chestnut Street between 34th & 40th streets. Unit 3 was roughly coterminous with the Black Bottom, a neighborhood of largely working class and working poor African American residents, who were displaced through eminent domain to create UCSC and University City High School.

The RDA acted in the interests of the West Philadelphia Corporation (WPC) and the School District of Philadelphia. The WPC was a non-profit consortium of higher education and medical institutions that included the University of Pennsylvania as the dominant partner/majority shareholder and, as junior partners, the Drexel Institute of Technology (now Drexel University), the Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science (now the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia), Presbyterian Hospital (now Penn–Presbyterian Medical Center), and Osteopathic Medical School (now the Philadelphia College of Osteopathic Medicine).1

The University City Science Center was the brainchild of the WPC and city agencies looking to recruit gifted scientists and scholars to “University City”; to attract the research units of major industries to form a “city of knowledge”; and to establish Philadelphia as a national leader in high-tech R&D. University City High School, while it was to be built by the School District of Philadelphia, was planned by the WPC as a high school of science & technology to be affiliated with the Science Center. The RDA condemned Unit 3 properties for urban renewal in 1966. In 1967 and 1968, RDA bulldozers leveled the blocks in the Market Street corridor to pave the way for the University City Science Center and University City High School.2

The chain of events that led to the formation of the WPC in 1959 and, in turn, the UCSC began with a spike in violent crime in an area in West Philadelphia known as the “Bottom,” a moniker derived from the area’s relative proximity to the Schuylkill River. The Bottom is distinguished from the “Black Bottom” (discussed below) by the former’s association with blocks north of Lancaster Avenue in Powelton Village, Mantua, and Fairmount. The proximate cause for the formation of the WPC was the murder of In-Ho Oh, a Korean doctoral student at Penn who resided in Powelton Village. The crime was committed on an April evening in 1958 by a marauding group of disaffected African American youth. The historian Eric Schneider has documented the rise in youth-related crime in the Bottom that had Penn, the lead institution in the WPC, as well as the progressive-minded neighborhood of Powelton Village, on tenterhooks in the late 1950s. Of no mean significance, the 10 youths who were imprisoned for killing In-Ho Oh were not from the African American-majority blocks around Market Street, known locally as the Black Bottom, which would be the primary target of post-1966 urban renewal in Unit 3. The Black Bottom was roughly coterminous with Unit 3.3

Unit 3 and the Fate of the Black Bottom

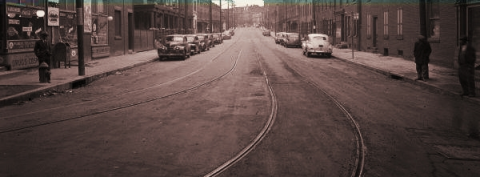

Home to a predominately working class and working poor African American neighborhood, the blocks that formed the Black Bottom were declared blighted by the Philadelphia City Planning Commission and the Redevelopment Authority (RDA) notwithstanding their strong communal qualities and vitality. Of no mean consequence to the people who lived here was the City’s eight-year dust- and debris-generating project of digging a subway tunnel under Market St. between 32nd & 45th streets, which was finally completed in 1956. Applying their own technocratic conception of “urban community,” which the RDA brusquely and narrowly defined in physical terms, the WPC’s urban renewal planners discounted the communal values, neighborly attachments, and cooperative activities of the Black Bottom residents, who were presented with a fait accompli in which they had no democratic voice. While outraged Black Bottom advocates in local and national black organizations were able to stave off the demolitions for four years, their legal options ran out in 1967.4

Walter Palmer, an attorney and the most visible spokesperson for the Black Bottom since the 1970s, recalls the neighborhood as a place where doors and windows were left open, and “anybody could walk in any time they wanted. . . . You could walk on the street 2 o’clock, 3 o’clock in the morning. My mother tells a story of how people would see her coming from Aunt Bea’s speakeasy walking home, the guys on the corner hiding their cigarettes, tipping their hat, and saying ‘Good evening, Mrs. Palmer,’ and [she knew] she was safe.” Palmer does not deny that violence occasionally flared in the Black Bottom, as it did in the city’s other low-income, segregated black neighborhoods, which were largely written off by city officials as beyond the pale of investment, restoration, or improvement—phrases like “consummate decay” and “morass of decayed and decaying buildings, some nondescript apartments and vacant lots” summed up the City’s prejudiced dismissal of the Black Bottom.5

Pearl Simpson, who came of age in the Black Bottom in the 1940s and would build a career as a Philadelphia lecturer, author, and social justice advocate, writes that the neighborhood was “dynamic and alive.” Simpson has rebutted the assertion printed in a 1954 Redevelopment Authority brochure that the Black Bottom contained “an assemblage of skid row habitués.” They labored to support their families within the restrictive confines of a racially segregated city. Dr. Simpson notes, “People were employed by area hospitals, small factories, as domestic helpers and maids, by the now-defunct Pennsylvania Railroad, and the defense industries during WWII. . . . Black-owned businesses in the area included barbershops, dressmakers, restaurants, beauty shops and variety stores.” And echoing Walter Palmer’s mother’s account: “This was the era of walking and visiting, no invitation required: locking front doors was unheard of.”6 In Philadelphia newspaper reports on the annual Black Bottom Picnic, which was first held in Fairmount Park in 1976, former residents have attested to the “neighborliness” of the neighborhood.7

Another witness to the Black Bottom’s communal life and vitality was Mike Roepel, an African American pensioner who made a career at the City Planning Commission. From 1948, his birth year, to 1960, Roepel lived in Hattie Hunter’s (his grandmother’s) house in the Black Bottom. Hattie was a pillar of the blocks around 36th & Market St. Her three-story house stood on the west side of 36th St. between Market & Filbert; Hattie and her late husband had received it as a gift in 1936 from Quakers who employed her as a housekeeper. To make ends meet, Hattie Hunter sold corn liquor to her neighbors, which was smuggled in from her hometown of Edenton, North Carolina, on Albemarle Sound. She sold her house to the RDA in the mid-1960s, and moved to 53rd & Pentridge St., in Southwest Philadelphia, where she was joined by other resettled Black Bottomers. “Thirty-sixth & Market reconstituted itself in that whole area,” a four-or five-block swath south of Baltimore Avenue around 54th St. & Florence Ave., in the Kingsessing neighborhood, some two miles from Unit 3. Roepel described the profound sense of loss experienced by these dispossessed people; while Hattie Hunter kept her old status as a wise community elder, other displaced residents lost their roles in the shakeup. “I can remember where some older folks deteriorated quicker because that’s what kept them alive . . . because they were it, as you say.”8

The Science Center and its projected affiliated high school were two of several WPC-supported projects in Unit 3, which displaced a total of 2,653 people; approximately 78 percent were African American. As many as, perhaps more than, 1,472 residents were displaced by the Penn/WPC “science center” strategy.9

The UCSC and University City High School developments accounted for just over half of the total Unit 3 displacements. Unfortunately, the RDA failed to track the relocation of the dispossessed families and individuals, most of whom were renters in absentee-owned buildings purchased by the Authority prior to demolition. Oral history sources point to the Kingsessing neighborhood in Southwest Philadelphia as the primary locality of resettlement. A belated student protest and seizure of Penn’s College Hall, spontaneously organized in the winter of 1969 and supported by Philadelphia-area college students and activists, compelled the Science Center to pledge to revert its holdings in the corridor north of 39th St. to the City for low-income public housing, which finally came to fruition in 1984.10

Since the incorporation of the Science Center in 1963, and especially following the Black Bottom removals, a coterie of scholars and activists have cast Penn as the primary instigator of a racist strategy to establish a cordon sanitaire in the Market Street corridor that would buffer Penn from the blight and crime the white WPC and city planners of that era associated with the low-income, Black-majority neighborhoods to the north and west of the campus.11 Archival research shows Penn’s dominance in the WPC and its heavy hand in Unit 3 planning. Of great consequence to the University’s community relations, the continuing hue and cry for reparations—in the form of college admissions and scholarships for the grandchildren and great grandchildren of the displaced residents—has always been directed at Penn, not Drexel or any other Science Center partner from the 1960s.

For two decades, a colorful mosaic mural erected near the front entrance of University City High School memorialized the Black Bottom, standing weathered until the high school’s closure and demolition, 2013–15. In their 2015 book on the University of Pennsylvania’s postwar history, Becoming Penn, Mark Lloyd and the author noted two possible interpretations of the Black Bottom as a place and space of communal identity: “that the concept of the ‘Black Bottom’ was an African American cultural construction to which white elites, prior to the clearances, were not privy, or that the concept acquired inflated significance after the removals as an identifier and rallying point for Unit 3’s black diaspora.” Edward Epstein, in his 2020 dissertation study, adheres to the former interpretation, persuasively affirming through oral history interviews with former residents, descendants of dispossessed families, and contemporary Black Bottom activists, that it was both a place and a space of contemporaneous communal identity extending back to the 1940s, if not earlier. Oral history interviews and the Black Bottom Mosaic Mural mapped the neighborhood as lying on the east-west axis of 34th & 40th streets between Ludlow, the first street below Market on the south, and Lancaster & Powelton avenues on the north.12

In August 2021, WHYY, Philadelphia’s PBS-affiliated station, reported on the Black Bottom Tribe, a number of whom were Black Bottom youths in the 1960s, among them Walter Palmer; they advocate for historical transparency from the institutions that engineered the 1967 and 1968 displacements and for historical markers honoring the memory of the Black Bottom. Highlighted is the experience of Andre Black, who was 18 years old when his family was forced from their home at the intersection of 36th and Market to resettle in the 1400 block of Divinity Street, in Kingsessing. A photo of Andre Black shows him in a t-shirt emblazoned with the message “The Black Bottom is not in University City. The university is in the Black Bottom.” He told the reporter, “Does anyone understand what urban renewal actually means? It means slum, ghetto, and poor.”13

Growth and Expansion of the Science Center: The Past Half-Century

The Science Center erected its first buildings between 1969 and 1971; its original headquarters was a converted industrial building on the 3501 block of Market Street, purchased in 1965. From the 1960s to the Millennium, the Science Center evolved as a consortium of 31 educational and medical institutions from throughout the Delaware Valley. In the 1960s, Penn was the majority shareholder; from 1969 to the Millennium, it controlled a plurality of the stock. The author’s research in Science Center records shows that beyond its successful recruitment of the Monell Chemical Senses Center in 1971, the Science Center Corporation was unable to recruit other major corporations with R&D departments; to stay afloat, the Science Center leased building space to organizations that were not research-oriented; the 15-story office building constructed on the northeast corner of 36th & Market to house the regional units of four federal agencies was the most glaring example.13

By the 1980s, the Science Center was in somewhat better financial shape. By the end of the decade, it would count 105 organizations with more than 6,000 employees, as well as a number of federally funded research projects assigned to its in-house research arm, the Science Center Institute. During Randall Whaley’s presidency, the Science Center redirected its mission to include incubating small technology businesses, claiming 106 start-ups (though of limited longevity) by the spring of 1987. Yet to keep its books balanced, it would continue to lease significant amounts of office space to administrative units of organizations that had little or nothing to do with science or technology development.14

From the Redevelopment Authority’s perspective, however, a more serious problem than filling the existing buildings was the Science Center’s failure to put up new ones to complete the research park. Leveled properties stood without buildings along Market between 36th & 38th streets; crime-friendly surface parking lots filled these blocks. Finally, in the early 1990s, the tide dramatically turned to accelerate completion of the research park. The booming Clinton-era economy spurred physical growth and a financial resurgence along Market St. that was sustained through the next quarter-century, impeded only temporarily by the 2008 recession. The Science Center also benefited from a national zeitgeist favoring the revitalization of so-called legacy cities and their renewed attraction to a new generation of liberal, high-tech-minded, professional elites. Even more, it was the beneficiary of Penn’s and Drexel’s spectacular turn-of-the-Millennium commercial developments along Walnut & Chestnut streets, respectively. Collectively, these initiatives have spurred the recentering of Philadelphia’s commercial core from Center City to West Philadelphia. These projects benefited from special services provided by the University City District, a partnership of the area’s anchor institutions, small businesses, and contributing residents inaugurated in 1997.15

The contemporary Science Center’s main attraction is new, eye-catching buildings housing high- tech laboratories and workspaces. Here are incubated small business startups in life sciences, clean technologies, IT, bioinformatics, nanotechnology, and diagnostics and devices. Both Drexel and Penn now own buildings in the Science Center: Drexel’s College of Media Arts & Design, formerly the Institute for Scientific Research, in the 3401 block of Market; Penn Medicine University City, an 11-story postmodernist tower at 3737 Market. The largest structure on Market St. is a 28-story postmodernist apartment tower/retail complex that replaced an unsightly parking lot on the northwest corner of 36th and Market, adjacent to (since demolished) University City High School. Under development at this writing (fall of 2021) is uCity Square, a megaproject undertaken by the Science Center and Wexford Science & Technology to construct an enclave of postmodernist buildings that co-locate work, residences, groceries/retail, recreation, and fitness on a single site designed for young, workaholic high-tech entrepreneurs.16

1. For the West Philadelphia Corporation, 1959–1983, see John L. Puckett & Mark Frazier Lloyd, Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 92–103, 222-224. In 1983, the WPC was restructured as the West Philadelphia Partnership, which granted voting rights on a co-equal basis to community organizations and offered greater representation of community voices.

2. Ibid., 92–103; see also & cf. Margaret Pugh O’Mara, Cities of Knowledge: Cold War Science and the Search for the Next Silicon Valley (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2005), 158–181.

3. Eric C. Schneider, The Ecology of Homicide: Race, Place, and Space in Postwar Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania, 2020), 32–50.

4. Puckett & Lloyd, Becoming Penn, chap. 4.

5. Walter Palmer, interview by John Puckett, 26 September 2008, 4 April 2010.

6. Pearl B. Simpson, “The Black Bottom Picnic,” Institute for Africana Social Work, May 1997, cited in Billy Yalowitz, “The Black Bottom: Making Community-Based Performance in West Philadelphia,” in Letting Go? Sharing Historical Authority in a User-Generated World, eds. Bill Adair, Benjamin Filene, & Laura Koloski (Philadelphia: Pew Center for Arts & Heritage, 2011), 157.

7. “Black Bottom Picnic” (photo), Philadelphia Tribune, 22 July 1986; “Black Bottom Reunion” (photo), Philadelphia Tribune, 31 July 1987; “For Some the Bottom was Tops, Memories of Old W. Phila. Neighborhood Pulls Them Back,” Philadelphia Daily News, 18 November 1988; “Rekindling the Ties of a Neighborhood,” Philadelphia Tribune, 27 July 1990; “‘Black Bottom’ Reunion Brings Old Friends Back to the City,” Philadelphia Tribune, 28 July 1992.

8. Mike Roepel, interview by John Puckett, 11 June 2009. For a similar statement on “loss of position,” see Pearl B. Simpson, The Black Bottom Picnic: A Collection of Essays, Poems, and Other Musings (Philadelphia: Author, 2005), 42–43.

9. Karen Gaines to “all concerned,” memorandum, 30 October 1968, University of Pennsylvania, UARC UPA4, box 214, folder “SDS versus University City Science Center—Student Affairs 1965–1970.”

10. Puckett & Lloyd, Becoming Penn, 103–111, 119–135.

11. O’Mara, in Cities of Knowledge, 158–181, supports these claims, as does Schneider, in Ecology of Homicide, 32–50; and Yalowitz, in “The Black Bottom,” 156–173.

12. Puckett & Lloyd, Becoming Penn, 106; Edward Epstein, “Race, Real Estate and Education: The University of Pennsylvania’s Interventions in West Philadelphia, 1960–1980” (Ed.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 2021).

13. Taylor Allen, “As Building Boom Continues in West Philly, Black Bottom Tribe Fights for a Sign of the Community They Lost, WHYY Plan Philly, 9 August 2021, accessed from WHYY.org, 15 August 2021.

14. John L. Puckett, “University City Science Center,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/university-city-science-center/.

15. For Penn’s commercial expansion between 36th & 41st streets on Walnut, late 1990s–early 2000s, see Puckett & Lloyd, Becoming Penn, 261–262; for Drexel’s growth in the same period as a commercial powerhouse on Chestnut Street between 32nd & 34th streets, see Scott Gabriel Knowles, Jason Ludwig, & Nathaniel Stanton, “The Promise of a New Century: Drexel and the City since the 1970s,” in Building Drexel: The University and Its City, 1891–2016, eds. Richardson Dilworth & Scott Gabriel Knowles (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017), 90–94. For the University City District, see Puckett & Lloyd, Becoming Penn, 257–258.

16. Puckett, “University City Science Center”; University City District, The State of University City 2021 (Philadelphia: UCD, 2021).