Once a High School

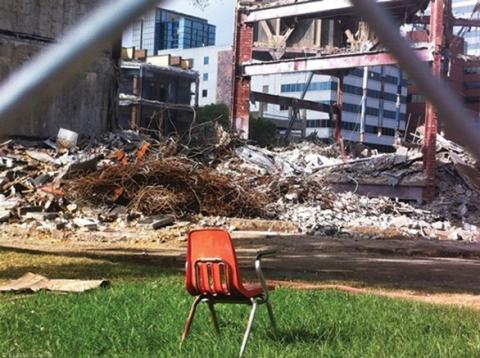

The financially strapped School District of Philadelphia closed University City High School in 2013; the District sold the campus to Drexel University in 2014; Drexel demolished the high school in 2015.

In 2013, the financially strapped School District of Philadelphia closed the 40-year-old, perennially under-resourced—and, by this time, significantly under-enrolled University City High School (UCHS). The District then listed the property for sale to the highest bidder. In 2014, Drexel University, in partnership with Wexford Science & Technology, purchased the 14-acre campus, as well as the Drew Elementary School and Drew’s Walnut Center annex on Warren St.—all treated as one unit for purposes of the $25.15 million sale. Drexel leveled these properties in 2015. This article focuses on the logistics of the high school’s demolition and the fate of several of its successful projects, including the Black Bottom Mosaic Mural.

This article notes the process by which the University City High School site was sold to Drexel University and leveled for redevelopment—a process that begs photographic comparison with the 1967–1968 leveling of the site (see the first article in this collection: “The University City Science Center and the Black Bottom”). It also notes what is known of the disposition of the high school’s plastic arts installations.

Drexel’s Big Purchase

In the late spring of 2014, the Philadelphia Inquirer’s Pulitzer Prize-winning architectural critic Inga Saffron wrote sardonically on the “battle royal over the University City High School on Drexel University’s western border,” a site that was “the stolen heart of Black Bottom, a district that was cruelly razed in 1968 to accommodate the University of Pennsylvania.” At issue was the most valuable property for sale in the School District of Philadelphia’s portfolio of closed schools. Drexel and its partner Wexford Science & Technology, a biomedical realty firm, posted the winning bid, a bit more than $25 million. Saffron compared it to a used-car sale. “It’s hard to imagine another major city simply selling such a high-profile piece of land, no strings attached,” she said. “Millions of taxpayer dollars were sunk into the site—first by the federal government through eminent-domain evictions of nearly 3,000 people; then by the city for the construction of the high school in 1971. (Intended as a showpiece, it was deemed a failure after just three years.)”1

Following the building’s closing in 2013 and Drexel’s purchase of the site in 2014, a remaining vestige of the former high school was the garden “farm” that was maintained by UCHS students, with adult oversight and resources provided by the Penn Netter Center’s Agatston Urban Nutrition Initiative (AUNI). Twelve high schoolers were paid as interns to receive on-the-job-training in urban gardening and nutrition; they marketed the farm’s produce at the weekly Clark Park Farmer’s Market; they also donated, or sold at low cost, a portion of their produce to low-income residents. Drew Elementary students were also engaged in the garden. They sold their mint to an award-winning choclatier.2

Yet the garden farm, and the greenspace it occupied on both sides of the projected 37th Street extension, was doomed. Drexel officials served notice for the property to be vacated by fall 2014. Critics described this eviction as a second Black Bottom removal.3 With respect to a possible relocation, it is important to note that this was a school-based community garden. Once the site was fully closed, a School District and Drexel action, there was no obvious way to sustain this project; even with continued funding, it is hard to imagine another West Philadelphia site that could replicate the long-in-the-making Penn–UCHS partnership and its communal ties, as well as the pedagogical value of the project.

By the time UCHS was shuttered, the Black Bottom Memorial Wall’s mosaic tiles, which were created by Penn and UCHS students under Andrea Zemel’s adroit direction in 1999 (see the previous article in this collection), had deteriorated badly while being perennially exposed to the elements. While some of the tiles were expertly gathered up before the 2015 demolition, the state of their decay likely rules out even a partial restoration.4

As for the two sculpted columns designed by the 1998 version of the Zemel-directed undergraduate–UCHS collaboration, Martin Bean Renovations single-handedly undertook “a multi-faceted uninstallation, removal, and storage of [the] two [18-year-old] concrete, mosaic art structures weighing an estimate of 8000-pounds combined.” When Drexel University failed to offer any funds to defray the roughly $50K cost of the operation, Martin Bean Renovations reallocated its company resources to save the structures in their entirety. The operation was successfully completed on 22 June 2015.5

For Andrea Zemel, her experience at UCHS was bittersweet. “It is (and was) such a disappointment that the University, my department (Fine Arts) and the local media (for the most part) took no interest in the telling of this story,” she has written. “I do believe there was a blurb on one television station but I can’t recall at this point which one. The dedication ceremony, as a result, was my last involvement with Penn. After considerable thought, I submitted my resignation to my department a month later and left academia altogether. I started a design business in NYC with my partner (and husband now of 20 years), and have continued to create mosaics as part of my studio practice. At the time, the lack of support—especially from my own department, was extremely demoralizing. Not a single member of the Fine Arts faculty attended the dedication ceremony, most likely since this kind of activity was not valued then as ‘serious’ art. Ironically, the mural gave so much more to the community placed as it was than in a gallery . . . they rallied to salvage what was left of it before the site was demolished in 2015.”6

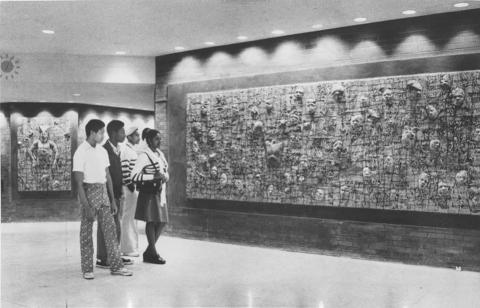

Three terra cotta murals—artistic artifacts from the high school’s early years—survived the property’s transfer to Drexel. Backstory: In 1975, the Redevelopment Authority’s “Percent for Art” program commissioned the ceramic artist John Costanza, a professor and department chair at the Moore College of Art & Design, to create three terra cotta murals for the new high school’s lobby—“22 feet long by 6 feet high; 24 by 7; and 3 by 5.”7 Foreshadowing the community-based approach of today’s Philadelphia Mural Arts program, Costanza engaged some 50 UCHS students in designing and handcrafting the murals, giving these youths an authentic stake in every phase of the production. Each mural portrayed African American historical figures chosen by the students, who helped carve the linoleum tiles for the project; some of the students also volunteered to have their faces incorporated as casts into the design. During the four months it took to complete the project, a video was made of the construction process and a “spiritual music performance” by the UCHS Choir.8

On the eve of destruction in June 2014, after he discovered that the school was boarded up, Costanza was allowed into the vacant building to inspect the condition of the murals. By now the building’s interior was a mess. "It looked like it was vacant for years," Costanza told the Philadelphia Inquirer. "There were broken windows, trash all over the place, and it was chained up. And I mean chained up." Costanza turned to the Drexel–Wexford partnership to save the murals.9

Wexford’s director of development, Pete Cramer, took the lead in assisting Costanza. His organization commissioned and funded Costanza’s son, Jon, owner of Sun Power Builders, to engage his firm to remove every tile by hand—a two-week process overseen by his father. The tiles were curated, boxed, and stored in John Costanza’s studio.10 Judith Guerrero, of the Redevelopment Authority, found a new home for one of the murals, fittingly the Moore College of Art & Design, at 1916 Race St., the very institution where Costanza had been a department chair when he completed the 1975 project. Honoring the mural’s reinstallation in the Outdoor Courtyard, a dedication ceremony was held on 28 July 2021.11

Black Bottom Denouement

University City High School’s demolition was completed in the summer and early fall of 2015, and the Drew and Walnut Center (Drew Annex) sites were also cleared.12 Once envisioned as a high school of science, UCHS had served as a comprehensive high school for 40 years.13

In the late spring of 2019, the Board of Education approved Drexel’s plan for constructing a new two-story school building on the former UCHS site in which to relocate two small high-performing schools—the Samuel Powel Elementary School (from 36th Street & Powelton Avenue) and SLAMS (the Science Leadership Academy Middle School). The final article in this collection, “The Market Corridor’s Millennial Building Boom,” takes up this project, viewing it in the context of Drexel’s recent campus expansion and the uCity Square megaproject.

1. Inga Saffron, “Planning Should Be Part of City School Sales,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 13 June 2014; see also “School District Has Deals to Sell Several Buildings,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 27 February 2014. In 2011, the School District reported losing 70,000 students; by 2013, just over 37 percent of the city’s public school enrollments were in charter schools. Desperate for money, the District chose to auction off “underutilized” schools to the highest bidder. In October 2013, the District listed seven schools (of a total of 28 citywide) for “expedited sale” by 30 June 2014; the combined sale value of the seven schools was $61 million; two of the seven were UCHS and the Drew School. “20 Offers to Buy Schools . . . But,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 January 2014.

2. “Struggle Grows, Fight Over Urban Farm Tied to Area History, Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 July 2014; Cory Bowman, associate director, Penn Netter Center, personal communication, 22 July, 2021. For more on the AUNI, see Lee Benson, Ira Harkavy, & John Puckett et al., Knowledge for Social Change: Bacon, Dewey, & the Revolutionary Transformation of Research Universities in the Twenty-First Century (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017), 124–139.

3. “Struggle Grows, Fight Over Urban Farm Tied to Area History.”

4. A reliable community informant provided this information.

5. Gweny Love to Rita A. Hodges & Ira Harkavy et al., 26 June 2015, copy courtesy of Penn Netter Center, 26 June 2021.

6. Andrea Zemel, personal communication, 26 June 2021. The zeitgeist would change, though twenty years would have to pass before Penn named its first Vice President for Social Equity and Community, then move swiftly to create the Office of Social Equity and Community—actions taken in the aftermath of Philadelphia’s and the nation’s dramatic, June 2020, post-George Floyd reckoning with police brutality and other longstanding racial injustices. Today’s Weitzman School of Design (formerly the Graduate School of Fine Arts), seems to value community-based urban design and mapping projects. At this writing (Fall 2021), a multidisciplinary committee of professors has been appointed by the provost to establish criteria for departments to follow in weighing the value of “civic engagement scholarship” that may not be publishable in disciplinary journals yet contributes to a community’s wellbeing or the solution of a social problem.

7. “Artist Looks for New Home for Old Murals,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 1 December 2014. In 1959, the RDA created the “Percent for Public Art” program, which requires new building construction or major renovation projects to include site-specific public art in the amount of up to one percent of the total budget.

8. John Costanza, dedication speech, Moore College of Art & Design, 28 July 2021, copy courtesy of John Costanza.

9. “Artist Looks for New Home for Old Murals.”

11. Costanza, dedication speech.

12. “University City High School Demolition Nearly Complete, ‘uCity Square’ To Take Its Place,” West Philly Local, 21 September 2015, accessed from http://www.westphillylocal.com/tag/university-city-high-school/, 23 June 2021.

13. Inga Saffron, “Rebuilding a University City Neighborhood—Again,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 29 January 2016,” reprinted in Saffron, Becoming Philadelphia: How An American City Made Itself New Again (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2020), 104–107; this article appears in a chapter titled “Age of the Megaprojects.”