University City High School

University City High School was built on land that was once the heart of the Black Bottom. It stood adjacent to the University City Science Center in Unit 3 and operated fitfully, from 1972 to 2013, as a comprehensive (general) high school in the chronically stressed School District of Philadelphia.

University City High School (UCHS) was originally planned as a racially integrated high school of science & technology affiliated with the University City Science Center. Yet it opened in the spring of 1972 as a comprehensive (general) high school with an enrollment that was large-majority African American. The perennially under-resourced high school was marked by attendance problems and most students underperforming on standardized achievement tests—and the school was riven with racial conflict between black and Asian students. After a period of improved stability, attendance, and achievement in the mid-1990s, UCHS entered the Millennium as a troubled high school in the chronically underfunded School District of Philadelphia. UCHS was officially closed in 2013. The District sold the site to Drexel University, and the building itself was demolished in 2015.

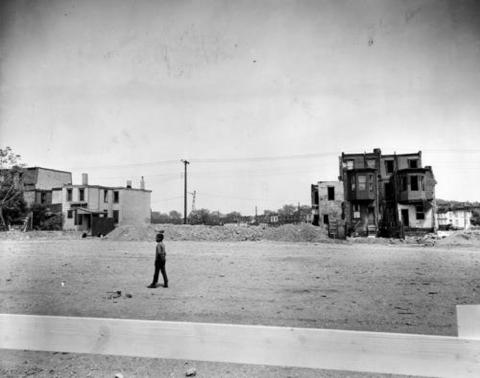

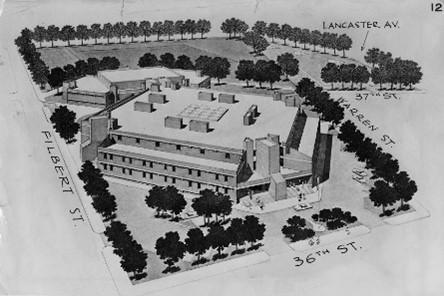

The Cold War trend of federal support for science education formed the national backdrop of the building of University City High School (UCHS).1 In 1963 the West Philadelphia Corporation (WPC) proposed a new high school modeled on the Bronx High School of Science and the Baltimore Polytechnic Institute. The University of Pennsylvania’s president, Gaylord Harnwell, regarded the proposed “Public High School of Science and Technology” as a logical extension of the University City Science Center, as it would presumably afford unprecedented opportunities to link secondary education directly to the work of practicing scientists. The WPC planners advocated locating the new high school in Unit 3 blocks from Filbert (one block north of Market) to Warren St. between 36th and 37th streets—a block from the heart of the Science Center.2

Harnwell’s plan never reached fruition. Strong opposition emerged from the West Philadelphia Schools Committee, a liberal civic group of racial integrationists who feared that a science & technology high school would be a magnet for University City’s white students, privilege UCHS, and thwart integration and “quality education” at West Philadelphia’s existing high schools—West and Overbrook, the former at 47th & Walnut St., the latter near 58th St. & Lancaster Ave.

Construction began on what was now a fourteen-acre high school site in the fall of 1968. Another four years would pass before the beleaguered edifice would finally open, by which time the conception of a Bronx Science-style high school was off the drawing board. In 1969, a burgeoning fiscal crisis in the school district, paralleled by Penn’s own mounting financial instability and institutional fatigue, boded poorly for continued support from any quarter for a specialized high school.

Reasoned speculation suggests two reasons for Penn’s dissociation from the high school project. First, the WPC’s proposal for a science high school was viewed by West Philadelphia blacks and their liberal white supporters as privileging the neighborhoods of University City, leaving the University open to “charges of unfairness and racial bias,” a political problem that was aggravated by Penn’s role in the Science Center. Second, Harnwell’s leadership team worried that the school district’s financial problems would leave the University holding the bag at a time when Penn’s own resources were diminished. With Jessica Oliff, who wrote a scholarly paper on University City High School, we would also conjecture that the University’s role in the West Philadelphia Free School presented an honorable and relatively inexpensive way out of this dilemma A radically innovative public high school housed at scattered sites around University City, the Free School opened in the fall of 1970 with a $60,000 contribution from Penn and the promise of relieving overcrowding at West Philadelphia High School. [According to Oliff] the Free School “required substantially less capital and did not require major cooperation with the school district. For this reason perhaps Penn felt the Free School offered a ‘safe’ way to fulfill its responsibilities to the community and education, without forcing the University to expend huge amounts of its own money.”3

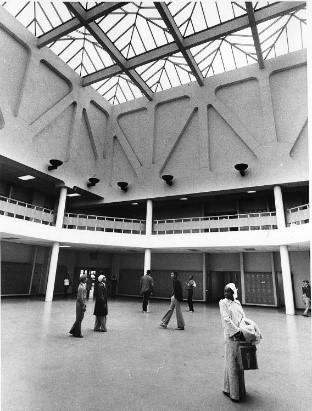

At all events, UCHS arose as a behemoth structure, a monolithic brick-and-mortar fortress, with a four-story central arch (facing 36th St.) flanked by two block-long, three-story wings (one along Filbert, the other along Warren). The architectural historian George Thomas writes that the building “took the form of a giant square surrounding a roofed-over interior courtyard—itself a telling image of an outside world that had lost its bearings. Like a Renaissance palazzo or John Haviland’s Eastern State Penitentiary, it appeared to be designed to defy urban insurrection. When the education staffers added grilles over the windows, the building looked even more prison-like. There was much of the urban prison in its internal demeanor of cinder-block corridors with metal doors as well.”4 UCHS evolved as a comprehensive (general) high school, with no specialized science & technology curriculum, no affiliation with the Science Center, and very few white students—in a 1979 article, the Philadelphia Daily News described UCHS as “very nonintegrated.”5 An art installation created with UCHS students and overseen by the ceramic artist and Moore College of Art & Design professor John Costanza, in 1975, was one feature that defied Thomas’s gloomy assessment of the building. We take up that inspiring story in “Once a High School,” the fourth article in this collection.

The controversy that embroiled University City High School in West Philadelphia is properly viewed in a larger context of racial politics in the citywide arena of public school governance in the 1960s and early 1970s. From 1963 to 1972, the president of the Philadelphia School Board (formally, the Board of Education) was the former Democratic mayor Richardson Dilworth, who prioritized progressive school reform and worked closely with Mark Shedd, the School District’s reform-minded, famously innovative superintendent. These two reformers ran afoul of the anti-black police commissioner and future mayor Frank Rizzo, who in 1967 disrupted a spirited yet peaceful march by thousands of demonstrating black students on the School Board’s headquarters and turned it into a police riot. Rizzo demagogically led a white backlash that got himself elected mayor in 1971 and ended the Dilworth–Shedd progressive reform era in the Philadelphia schools. The city’s removal of Rizzo’s statue in front of the Federal Building in Center City during the racial protests of the summer of 2020 attests to Philadelphia blacks’ strong antipathy to the twice-elected Republican mayor.6

Times of Trouble

Within a year of its opening, University City High School was riven by juvenile gang violence, and assaults on teachers took place in the building’s labyrinthine interior and exterior hallways. Three rival gangs were able to gain access into the building and wreak havoc in the school’s lunchroom and hallways, as the Bureau of Licenses and Inspections, for fire-safety reasons, would not allow any of the school’s nine doorways to be locked. In the fall semester of 1975, nine assaults on teachers were reported—a situation the Philadelphia Teachers Union described as “chaotic.”7

Later in the decade and into the 1980s, conflict and occasional violence flared between black students and enrolled Hmong, Cambodian, Vietnamese and Laotian refugees—with blacks comprising about 80 percent of a total student enrollment of 2,100; Southeast Asians about 15 percent; and whites roughly 5 percent. “In late 1981, two Asian students were stabbed during one incident and others were beaten in a lunchroom brawl that spilled out onto the street,” the Philadelphia Inquirer reported. “A year ago, an 18-year-old Vietnamese refugee was hospitalized for more than a month after his neck was broken when he was assaulted in a school hallway.”8

From the fall of 1995 to the spring of 1998, UCHS experienced several years of relative stability and improvement under a new principal, James “Torch” Lytle (“Torch” because of his red hair), an experienced progressive educator and high-profile administrator in the School District, also a highly regarded adjunct professor in Penn’s Graduate School of Education. On his arrival at UCHS, Lytle confronted a roiling situation, as noted by the Philadelphia Inquirer’s editorial board: “Gangs marked their turf by painting the walls. Students fought at the least provocation, while shouting matches among staffers were routine. Racial tensions bubbled.” The newspaper cited the highlights of Lytle’s tenure: “First, he spent three months of listening to faculty, parents and staff, who pushed to expand six existing small programs where kids were thriving. He invited faculty to form four new ‘small learning communities’ and put students in these academies for their entire four years. He began a ‘twilight’ program for older dropouts. Fifty-six of these ‘dropbacks’ graduated last month” (June 1998).9

Mindful of the value of local knowledge and experience, Lytle enlisted a number of the school’s West Philadelphia-rooted non-teaching assistants (NTAs) as hallway counselors to troubled students. Under Lytle, the school halved its number of violent incidents and boosted attendance. Yet while the percentage of 11th graders achieving reading mastery as measured by the School District improved by 40 percent over the pre-Lytle performance, only 18.7 percent of the class was reading at grade level. Lytle left the School District in the summer of 1998 to become superintendent of the Trenton, NJ, city schools.10

The high school’s low achievement record happened despite the efforts of a number of truly dedicated teachers. In the 1990s, the author was familiar with the exceptional work of energetic teachers affiliated with the Philadelphia Writing Project, for example, UCHS English teachers Dina Portnoy and Margot Ackerman; and UCHS social studies teacher Theresa Simmonds, a former Rhodes Scholar and an affiliate of Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships.

Penn’s academically based community service (ABCS) courses had a presence in the high school in its final decades. Penn’s Moelis Access Science program began in 1999 with initial support from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and, in 2006, a naming gift from Ronald and Kerry Moelis, a Penn alumnus and his spouse. Approximately a dozen ABCS courses in Penn’s STEM departments were affiliated with the program. “Community Physics Initiative,” taught by Professor Larry Gladney, associate dean for the Natural Sciences, was illustrative:

Aligned with the School District of Philadelphia’s curriculum for introductory high school physics, Gladney’s course links the practical and theoretical aspects of foundational physics. By developing and teaching weekly laboratory exercises and classroom demonstrations at [University City High School] Penn students learn science by teaching it.11

Two arts & culture highlights of the Lytle era, both mediated by the Netter Center, stand out in the high school’s history—the Black Bottom Mosaic Mural (also called the Black Bottom Memorial Wall) and the Black Bottom Performance Project. These projects are the focus of the third article in Once the Black Bottom. The fourth article includes, among other topics, the fate of the UCHS garden “farm” and produce-marketing operation, which was mediated by and sustained for 15 years with Netter Center resources and personnel.

The Final Years

In January 2002, President George W. Bush signed the bipartisan No Child Left Behind Act, which mandated “corrective action” (i.e., sanctions) for schools whose students consistently failed to meet an acceptable standard of mastery, or AYP (“adequate yearly progress”), on standards-based, criterion-referenced tests in reading and math. Here it is important to note that Congress has no constitutional authority for education. That is, education is not a right protected by the U.S. Constitution; it is a power reserved for the states by the 10th Amendment. Yet the feds held the purse strings: a state’s eligibility for federal Title I moneys was contingent on compliance with NCLB. That, of course, did not mean that a state could not produce vague performance standards, design easy tests, or set a low bar for reading and math mastery in any or all of the federal law’s disaggregated categories for assessment. Indeed, the education departments in many states resorted to one or more of these strategies. NCLB’s 12-year mandate ended in 2014 with most states badly in arrears on meeting AYP.12

In 2008, the Philadelphia School Reform Commission, the School District’s governing body at the time, recruited Arlene Ackerman from San Francisco as the new District CEO. “Turnaround” was the buzzword of late-2000 aughts school reformers, and the authoritarian, hard-driving Ackerman took on the turnaround of the District’s underperforming schools. University City High School was near the top of the Reform Commission’s list as an NCLB problem. From the mid-2000 aughts, the high school’s scores on the Pennsylvania State School Assessment (PSSA) were below benchmarks for four consecutive years and the school was earmarked for a “Corrective Action II” overhaul. In the spring of 2010, Ackerman designated UCHS as a “Promise Academy,” one of six low-performing schools districtwide with that designation. (Promise Academies were one category of low-performing schools targeted for dramatic improvement in Ackerman’s “Renaissance Schools” initiative.)

Prior to the start of the 2010-2011 school year, the first cohort of Promise Academies received a staffing overhaul, including a new principal for most schools and partial replacement of school staff. Unless the principal had been at the school for less than two years, the central office identified, interviewed, selected, and assigned new principals to each school. All teachers at the school were forced-transfer but were eligible to reapply for their positions. The school was allowed to rehire up to 50% of teachers who chose to reapply through site selection. All staff remained part of the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers (PFT) union and employed by the District.

Promise Academies were required to use a prescribed set of instructional interventions, curricula, and programs, including Corrective Reading and Corrective Math (McGraw Hill Education, 2008), as well as world language studies. Schools also received substantial technical and building improvements in the first year, such as Smart Boards, computers, and newly painted facilities. The model required schools to implement climate and culture protocols, such as daily town hall meetings, daily recitation of the Promise Academy pledge, and the facilitation of school events once per quarter. Students were expected to wear Promise Academy uniforms.13

The Promise Academies got off to a good start in the first year of the program, with delivery of promised resources and implementation of required protocols. The second year, however, was a disaster, as the School District’s financial situation, which was always shaky, took yet another serious downturn, showing a $600 million-plus budget deficit. Contractual disputes with the Philadelphia Teachers Union over teacher forced transfers exacerbated the financial crisis; in combination, these problems undermined the “promise” of Ackerman’s reform program.14 Ackerman herself was on shaky ground, not only with the budget crisis but also with her underreporting of pervasive violence in the schools, her frayed relationship with Mayor Michael Nutter, and some high-profile PR fiascos to her credit. The School Reform Commission fired her in 2012—after inexplicably renewing her contract six months earlier.15

Thus ended Ackerman’s “Imagine 2014,” the urban school reform agenda she so boldly proclaimed in 2008, which only lasted only three and a half years—and with it any hope that University City High School might stave off closing. The bell tolled for UCHS in December 2012, when the School Reform Commission announced that the high school would close following the spring semester of 2013. By this time, UCHS showed an enrollment of 506 students in grades 9–12, in a school built for at least 2,100.16

1. John L. Rudolph, Scientists in the Classroom: The Cold War Reconstruction of American Science Education (New York: Palgrave, 2002).

2. Dick Righter (chairman, West Philadelphia Schools Committee) to Leo Molinaro (executive director, WPC), 26 December 1963, University Archives & Records Center, UPA 4, box 154, folder “Community Relations—West Phila. Corp. Science High School 1960–1965.”

3. John L. Puckett & Mark Frazier Lloyd, Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000 (Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 107, 112–114; interior quotes from Jessica Lee Oliff, “University City High School: An Experiment in Innovative Education” (Senior honors thesis in history, University of Pennsylvania, 2000), the definitive study of the origins of UCHS. For more on the Free School, see on this website Kim-Jamey Nguyen and John L. Puckett, “The West Philadelphia Community Free School,” https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/stories/west-philadelphia-community-free-school.

4. George E. Thomas, “From Our House to the ‘Big House’: Architectural Design as Visible Metaphor of the School Buildings of Philadelphia,” Journal of Planning History 5, no. 3 (2006): 218–40.

5. “School Deseg Tours Paint Pretty Picture,” Philadelphia Daily News, 17 October 1979.

6. Mathew J. Countryman, Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2005), chap. 6—a richly descriptive and incisive account.

7. “Violence Mars New School,” Philadelphia Daily News, 8 February 1972; “University City High School Student Knifed,” Philadelphia Tribune, 14 November 1972; “U.C.H.S. Student Fights ‘Unjust’ Expulsion,” Philadelphia Tribune, 16 December 1972; “Teachers under Attack,” Philadelphia Daily News, 9 January 1976.

8. Bob Perkins, column, “Blacks Wrong in Attacking Asians,” Philadelphia Tribune, 22 December 1981; “School Security Boosted, University City High Hit by Racial Violence,” Philadelphia Daily News, 11 November 1983; “Racial Strife Resurfaces at U. City High School,” Daily Pennsylvanian, 30 November 1983; “School Transfers Assault Victim: Vietnamese Student Objects to Leaving His Friends,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 8 December 1983; “Tensions Said to be Easing in Asians’ Neighborhoods,” Philadelphia Daily News, 6 November 1984; “Bridging Phila. Cultural Gaps, At Retreat Blacks and Asian Students Come Together, Philadelphia Inquirer, 2 December 1984.

9. “Keep the Faith, Educator Taking His Belief in Students to Trenton,” editorial, Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 July 1998.

11. Lee Benson, Ira Harkavy, John Puckett et al., Knowledge for Social Change: Bacon, Dewey, & the Radical Transformation of Research Universities in the Twenty-First Century (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 2017), 103.

12. The most comprehensive account is David K. Cohen & Susan L. Moffitt, The Ordeal of Equality: Did Federal Regulations Fix the Schools? (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2009). NCLB was a reauthorization and updating of the 1965 Elementary & Secondary Education Act (ESEA). Cohen & Moffitt trace the legislation’s evolution across four decades to show that NCLB reworked elements of previous revisions of ESEA, but was plagued from the beginning by the leverage the states had to “fake good” to receive their Title I funds. This incisive book answers the question posed in the subtitle with a resounding no. Published five years ahead of NCLB’s terminal date, the book shows that NCLB was doomed from the beginning by the huge disconnect between its hyperbolically extravagant goal—that all children would perform at grade level (worded as “proficiency”) or better by 2014—and the limited resources available to teachers because the legislation was woefully underfunded.

13. Kati Stratos, Tonya Wolford, & Adrienne Reitano, “Philadelphia’s Renaissance School Initiative after Four Years,” Perspectives on Urban Education 12, no. 1 (Spring 2015), accessed from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1056675.pdf, 20 June 2021.

15. The author closely followed, through his reading of newspaper accounts, his on-site observations, and his participation at meetings, the events and controversies of the Ackerman years sketched in this section. In 2012, the Philadelphia Inquirer won a Pulitzer Prize for its series on underreported violence in the Ackerman-era Philadelphia schools.

16. “School Closings Bring Worry and Anger,” Philadelphia Inquirer, December 14, 2012. Elaine Simon, director of Penn’s Urban Studies Program, and the author taught an academically based community service course at UCHS in its last year of operation. Their teacher partner at the high school was the social studies teacher A.J. Schiera, a Lenore Annenberg Teaching Fellow who was recognized as a Philadelphia School District Distinguished Teacher in 2013. They witnessed high anxiety among juniors and sophomores as to where they might be reassigned in the fall of 2013.