Woodside Park

Woodside Park was an amusement park which thrilled Philadelphians with its attractions for almost 60 years.

In 1897, the Fairmount Park Transportation Company built Woodside Park at the end of its new Fairmount Park trolley line. The park boasted scenic attractions, thrill rides, and concessions which many Philadelphians remember fondly. But Woodside Park memories are marred by its discriminatory admittance policies at the park’s swimming pool. Activism from Philadelphians eventually wore down park management, but the park closed only three years later in 1955.

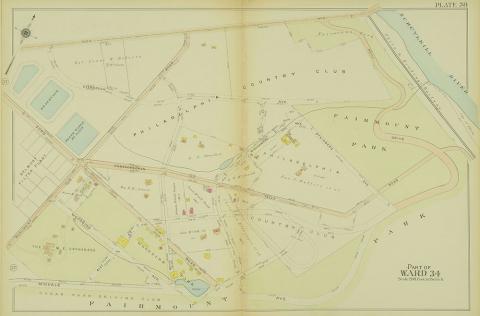

Woodside Park was an amusement park located just outside Fairmount Park near the intersection of Ford Road and Monument Road. For years its attractions lured children from throughout the Philadelphia region:

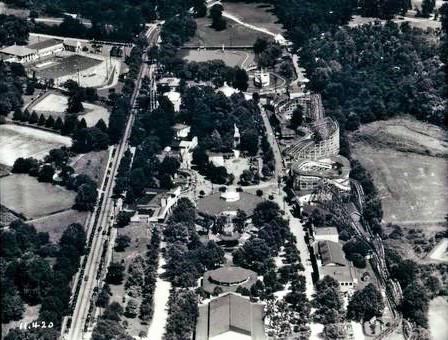

Woodside Park closed in 1955, so I have no chance of enjoying its features and activities today. But, I still have vivid memories of its funhouse and its scary experiences. The bumping cars, the spooky house, the boat ride on Chamonix Lake, the Caterpillar ride, its Merry-Go-Round and, of course, its famous roller coaster, "The Wildcat," are attractions that I feel I experienced just yesterday.[1]

Woodside was the last stop on the Park Trolley line and was created and owned by the trolley management, the Fairmount Park Transportation Company. Trolleys were still a novel thrill for city-dwellers at that time and the owners of trolley lines often created attractions at the final stop to increase the number of passengers riding for recreation.[2] In fact, the bumpy, 10-mile track through the scenic park was an unofficial attraction as well. In Woodside’s first two decades the track would have taken passengers past sheep grazing and the “Gentleman’s Driving Park” which allowed fast racing contrary to the 7 miles per hour limit in the rest of the park.[3]

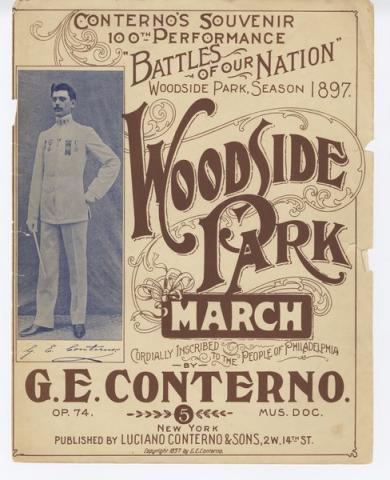

Thousands attended Woodside’s opening day on June 12, 1897. The park featured a shooting gallery, a casino, a lake dotted with gondolas, a dance ballroom, and a musical spectacle with mechanical special effects. The park also had a scenic railway—the forerunner of the thrill rollercoaster—called Thompson’s Scenic Railway. The park was an immediate success and firework displays occurred regularly on Friday nights.[4]

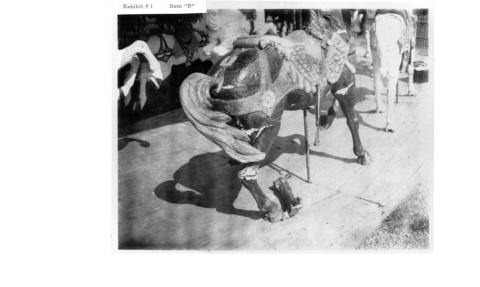

In 1908, Woodside received what would become its most beloved rides. The carousel was the work of North Philadelphia’s Dentzel Carousel Company.

The carousel was built “Philadelphia-style,” which means the animals are sculpted in vibrant, lifelike detail. The animals in the outer ring are stationary, while those on the inside rings rise and fall in a slow gallop. There are 52 hand-carved wooden animals in the menagerie, including 40 horses, four cats, two pigs, two goats and four rabbits. […] The standers, or outside row horses were originally designed and carved by Daniel Muller—considered to be one of the foremost carvers of his time. One of the most intriguing and unique features are the 1,296 lights that illuminate the carousel.[5]

Over the next few decades the park expanded with a kiddie park, a rollerdrome, and a fun house, concessions like Skee Ball, and several more rollercoasters. Woodside also had a ballroom which featured an orchestra to provide dance music.[6]

Though technically the rides were open to all, Woodside Park was well-known for its notorious Jim Crow practices in places like the rollerdrome (picketing resulted in its closure) and the Crystal Pool. Built for a cost of $250,000, the Crystal Pool opened to the public in 1926. It featured an artificial sand beach, a kiddie pool, and a large main pool with a deep-end. The attraction spanned four acres and had a 5,000-swimmer capacity.[7]

It was well known by Black patrons of the park that they were not welcome in the pool, a feeling which was reinforced by Woodside’s thinly-veiled White’s-only membership program.

When African Americans attempted to gain entrance, pool officials told them that only members could enter. If a black person attempted to pay the dollar membership fee, they would be told that the pool was full, and was turned away often in an aggressive manner. These black residents also reported seeing many whites gain entrance to the pool without membership passes.[8]

A Black man attempting to enter the pool in 1927 was seized by the collar and taken to a guard house. There he was physically threatened and then placed under arrest after asking how he could obtain membership to the pool.[9]

In August of 1945 a large-scale plan to expose Woodside’s discriminatory practices, led by West Philadelphian teacher and activist Arthur Huff Fauset, led to the arrest of a guard, the president of the park’s swimming club, and long-time park manager Norman S. Alexander. Fauset, accompanied by a reporter and a photographer, documented evidence that they had been denied entrance while White patrons had never been required to show a membership card. A simultaneous effort at the same time by coordinating groups led to the closure of the rollerdrome.[10] The Crystal Pool remained open only to White patrons and the case against Alexander and his associates was dismissed on a technicality the following spring. Protests, picketing, and letters to the mayor went on for several years.

The discriminatory practice came to an end in 1952, when the city of Philadelphia took over management of Crystal Pool. Reportedly, Woodside’s new management (Alexander died in January 1952) chose to lease the pool to avoid further disputes about their admittance policies.[11]

Woodside Park closed following the 1955 summer season. The reasons for its closure were not official but several factors pointed to its end. The death of Alexander, often cited as the guiding force behind the park’s attractions, may have left the park without a clear path forward. It had already outlasted the impetus for its construction by almost 10 years. The Fairmount Park Trolley shut down in 1946. Willow Park, Woodside’s close local competition, was still accessible by public transit. Rising property values may have been the ultimate contributing factor—Woodside was sold to a development company.[12]

At least one part of Woodside lives on in West Philadelphia. The Dentzel carousel is housed at the Please Touch Museum, 10 blocks from its original home.