Haddington Homes: “Row Housing as Public Housing”

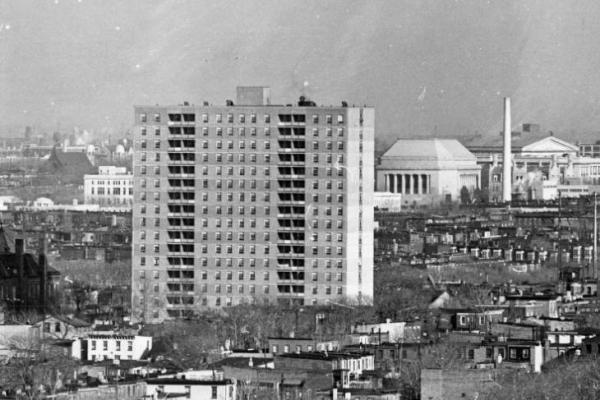

In the late 1950s, the Philadelphia Housing Authority, as an alternative to building elevator towers, experimented with “conserving” (i.e., renovating) used housing as public housing in Haddington, a working-class neighborhood in racial transition.

Consistent with the 1954 Housing Act’s emphasis on housing rehabilitation, or conservation, the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) designated 200 abandoned or badly deteriorated houses for conservation and single-family occupancy in the Used Housing Program in Haddington, a working-class neighborhood in racial transition. The late 1950s–early 1960s experiment with “row housing as public housing” was not successful. In the early 21st century, the PHA built two new low-rise projects in this now African American neighborhood: Haddington Homes and Arch Homes.

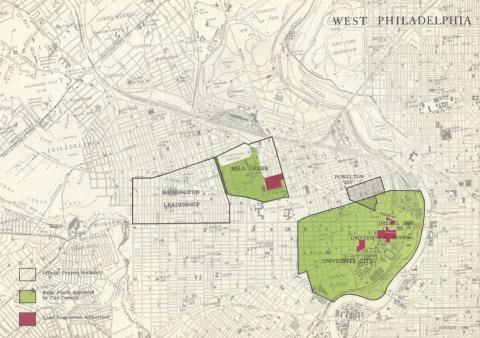

The 1954 Housing Act shifted the federal focus in postwar urban redevelopment from slum clearance and housing development to housing rehabilitation, or conservation. In this vein, Philadelphia’s planning coordinator, William Rafsky, designated Haddington in West Philadelphia as the first neighborhood to demonstrate “row housing as public housing.”[1]

Rafsky was deeply worried by the Philadelphia Housing Authority’s segregated towers. His proposal for scattered-site public housing “in white neighborhoods such as Logan, Olney, and the Northeast,” however, crashed on the shoals of staunch white opposition. Rafsky was allied with the progressive Joint Committee on Public Housing Policy (JCPH).

This committee had been formed by the Philadelphia Housing Association, which was directed in the 1950s by Dorothy Montgomery, and the Citizens Committee on the City Plan. The JCPH, whose chair was Jefferson Fordham, dean of the University of Pennsylvania Law School, decided on rehabilitated “used housing” as an alternative strategy, although it wasn’t clear how used housing would effectively promote racial integration. In any case, the JCPH proposal was supported by the Philadelphia Housing Authority (hereafter, the Authority) and endorsed by the U.S. Public Housing Administration, whose director, Charles Slusser, viewed it primarily as a cost-saving measure for the federal government.[2]

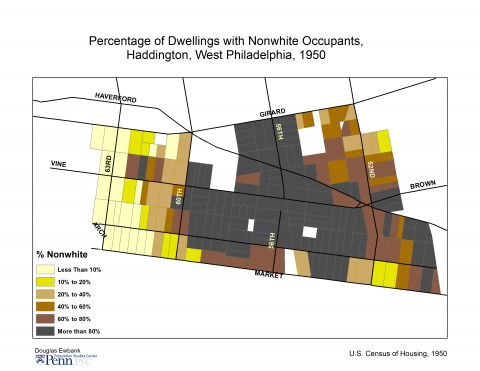

Haddington, the designated neighborhood for the Used Housing Program in West Philadelphia, the nation’s first, was bounded east-west by 52nd and 63rd streets, south-north by Market Street and Girard Avenue.

In the late-1950s, Haddington was a “non-industrial, middle-aged, white-collar neighborhood,” with “tightly packed attached, duplex, and free-standing dwellings,” whose residents bristled at the growing numbers of African Americans in West Philadelphia. The neighborhood was marked as “C” or “Conservation Area,” shorthand for on-the-verge-of-blight.[3]

Supporters of the plan, operationalized in 1958, gambled that whites primed to leave the working-class neighborhood, which was designated a “transitional area,” would choose to remain if affordable, attractive housing were available to them. Under the plan, the Authority “purchased two-hundred single homes for renovation and occupancy by single families in the Haddington Area.” Rehabilitation of the first house established a precedent for the others:

This two-story dwelling had been built at the turn of the century. Before the Authority bought the vacant, deteriorating dwelling from the bank, it was the only abandoned house on the block. The Authority completely modernized it, redecorated it with a new concrete porch adorned with an iron railing, and installed brand new windows, electric fixtures, kitchen appliances, plumbing, and wallpaper.[4]

By the late 1960s, the gamble to achieve a modicum of racial integration in Haddington, and other working-class neighborhoods, was doomed. Philadelphia’s civil rights movement had exposed the intense frustration of the city’s blacks, who endured “high unemployment, gnawing poverty, police brutality, abominable, overcrowded housing conditions, and poor city services, plus the bulk of the Authority’s mainly black-occupied high-rise public housing.”[5]

In 1964, the North Philadelphia ghetto erupted in rioting. Confronted with white hostility that was further inflamed by black volatility, the city’s housing planners gave up trying to integrate public housing. Henceforth, the used housing program and scattered-site housing more generally would be restricted to segregated neighborhoods, and 90 percent of the renters would be African American.

William Rafsky, who coordinated the redevelopment of used housing, focused the Authority’s attention on North Philadelphia’s decaying housing stock. He enlisted private developers as partners with the Authority. Selected developers contracted by the Authority would purchase and renovate abandoned houses on the open market and then sell them to the Authority at “predetermined list prices.”[6]

This arrangement, which involved a massive number of rehabilitations, soon outstripped the Authority’s capacity to monitor the quality of the developers’ work. Accordingly, City Hall, in 1966, got the state to authorize the Philadelphia Housing Development Corporation (PHDC).

The PHDC was a land bank that would assemble the properties and oversee the used house process. The process did not go well. The problem of quality control persisted, labor costs to developers who had to deal with contentious unions produced slim profits, and the Authority was beset with soaring maintenance costs. By 1969, the used house program was viewed by news media and the federal government as dysfunctional.[7]

Philadelphia’s used housing program fell far short of the high expectations that had infused it in the late 1950s. This disappointment included Haddington Homes.

Context mattered greatly. In the postwar decades, deindustrialization and the outflow of jobs to suburbia intersected with the prospect of federally guaranteed home mortgages to push “white-collar and working-class whites” to seek greener pastures outside the city—resources and opportunities that were denied to most African Americans. White flight diminished the city’s tax base at a time when the federal government was losing interest in public housing. “Neither the Housing Authority nor . . . [those] left behind possessed the means to maintain blocks of aging row houses, whether built in the 1880s, 1890s, or late 1930s.”[8]

In the new Millennium, the Public Housing Authority has built new (as opposed to conserving old) row houses in the form of Arch Homes—73 units at 56th and Arch St. (a new version of an older project on the same site), and Haddington Homes—148 units in blocks around 55th and Vine, an adoption of the name assigned to Haddington’s 1950s–60s used house program. Both housing sites are administered from the PHA office at 5520 Vine Street.