Public Housing’s Backstory

In the decades after World War II, segregated public housing was planned to provide “safe and sanitary housing” for low-income residents—an aspirational goal that lacked both resources and political will to bring to fruition.

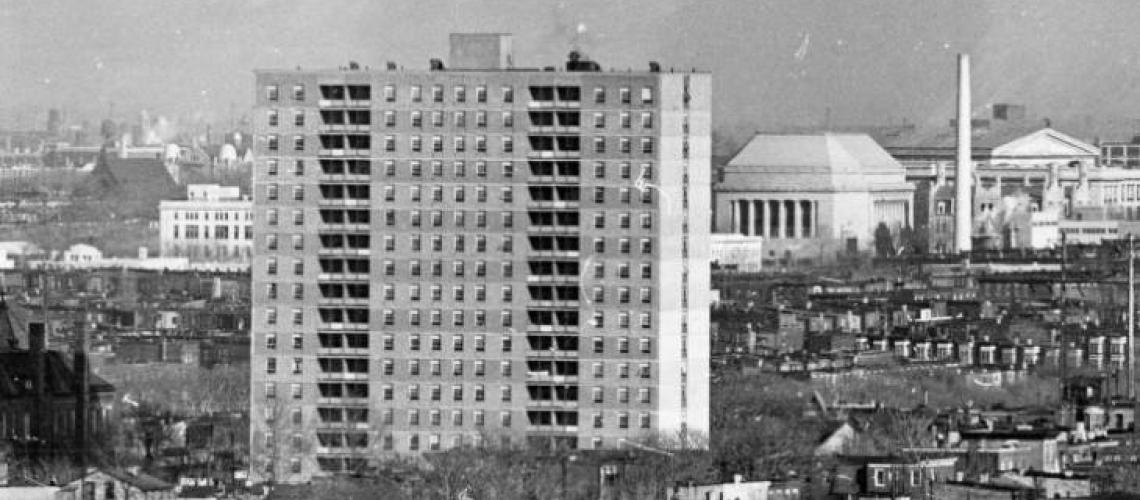

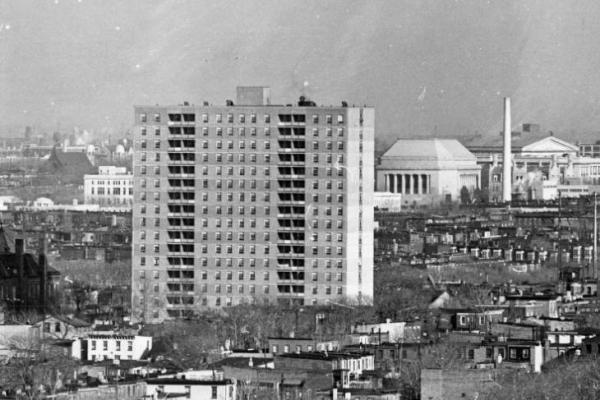

The Philadelphia Housing Authority, with funds allocated by the Housing Act of 1949, built high-rise, modernist apartment buildings in West Philadelphia in a failed effort to provide adequate housing for the area’s low-income black population. Three high-rise projects rose between 1958 and 1962. In the two postwar decades, the Authority also experimented unsuccessfully with “row housing as public housing.”

In September 1937, Congress passed the Wagner-Stegall Act, which created the U.S. Housing Authority (USHA). The USHA was established to provide loans to local housing agencies for slum clearance and housing for low-income families. More precisely, the legislation restricted the program to “poor families ‘who cannot afford to pay enough to induce private enterprise to build safe and sanitary housing for their use.’” Just weeks before Congress authorized Wagner-Steagall, Philadelphia’s City Council created the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA).[1]

Events proved that Wagner-Stegall was insufficient to meet the crisis of housing scarcity. With a commitment to underwrite 810,000 new units, Title III of the Housing Act of 1949 kicked new life into public housing. Philadelphia would be no exception.[2] The urban housing historian John F. Bauman narration of the political backstory of the city’s public housing after 1950 merits quoting at length:

In that year, the city’s politically progressive and Democratic-aligned “Young Turks,” led by Philadelphia social elites and future city mayors Joseph Clark and Richardson Dilworth and the young, Princeton- and Harvard-educated lawyer Walter M. Phillips, wrested city government from decades of Republican Party control. Committed to modernist urban planning, government efficiency, and social and racial justice, the Young Turks framed a new city charter (adopted in 1950), revamped the city’s moribund planning commission, and created a Commission on Human Relations dedicated to racial justice. Abetted by Washington and the newly enacted . . . Housing Act of 1949, which, for the first time, pledged the nation to “a decent home in a decent environment for every American,” city reformers such as Dorothy S. Montgomery (director in the 1950s of the Philadelphia Housing Association), Walter Phillips, G. Holmes Perkins (dean of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Fine Arts), and the Cornell-educated architect planner Edmund Bacon . . . viewed public housing as part of the process of excising away Philadelphia’s obsolescent industrial past and ushering in a modern and more physically attractive future for a “Better Philadelphia.”[3]

The 1940s wave of the Great Migration of blacks from the Jim Crow South gave Philadelphia the nation’s third largest African American population by 1950, a total of nearly 380,000. Arriving primarily from South Carolina, North Carolina, Virginia, and Georgia, the wartime migrants settled primarily in West and South Philadelphia, secondarily in North Philadelphia, which was already 39 percent African American by 1940 and would, by 1970, be 93.3-percent African American and the city’s most segregated area. Continuing in-migration and natural population increase would rachet the black citywide total to 653,791, comprising 33.6 percent of the Philadelphia total.[4]

The housing situation of the post-World War II in-migrants to Philadelphia is properly viewed in the context of expanding employment opportunities for the black middle and working classes and, simultaneously, declining opportunities for the black working poor.

Liberal reform of the city’s Home Rule Charter included significant antidiscrimination measures that opened thousands of municipal jobs based on civil service exams to blacks, who, by 1963, held 39 percent of the city’s municipal jobs and 36 percent of its public-school teaching positions. Rising employment spurred increased homeownership: By 1956, Philadelphia’s black homeownership rate was 43.8 percent.[5]

One critical downside of this story is that working poor blacks who might have found subsistence-supportive employment on the bottom rungs of the city’s wartime manufacturing industries were in dire straits when these enterprises either failed or departed for the suburbs in the postwar era. As the historian Matthew J. Countryman tersely puts it: “As the latest to arrive in the city, poorly educated and unskilled black workers were most vulnerable to these changes in the labor market.”[6] The growth of this largely disfranchised population group outstripped the city’s existing housing supply.[7]

The 1960 U.S. Census would show that two-thirds of Philadelphians living in substandard housing were nonwhite.[8] Segregated public housing for the black unemployed and working poor would be organized to provide, in theory at least, “safe and sanitary housing” for this segment of the population.

The Philadelphia Housing Authority, with funds allocated by the 1949 housing legislation, built “eleven-, fifteen-, and eighteen story modernist towers” in a failed effort to resolve the city’s housing crisis.[9] Three high-rise tower projects rose in West Philadelphia between 1953 and 1962: Mill Creek Homes, Mantua Hall, and West Park Apartments, all built in racially segregated neighborhoods.

The 1954 Housing Act shifted the federal focus from slum clearance and housing development to housing rehabilitation, or conservation. In this vein, the city’s planning coordinator, William Rafsky, designated Haddington in West Philadelphia as one of four neighborhoods that would experiment with “row housing as public housing.”[10] The strategy of “row housing as public housing” would be taken up again at the turn of the Millennium at Lucien E. Black Homes in West Philadelphia’s Mill Creek neighborhood.[11]

[1] John F. Bauman, Public Housing, Race, and Urban Renewal: Urban Planning in Philadelphia, 1920–1974 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987), 42 –45, quote from p. 44; Joseph Heathcott, “Myth #1: Public Housing Stands Alone,” in Public Housing Myths: Perception, Reality, and Social Policy, eds. Nicholas Dagen Bloom, Fritz Umbach, and Lawrence J. Vale (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 31–46.

[2] Heathcott, “Public Housing Stands Alone.”

[3] John F. Bauman, “Row Housing as Public Housing: The Philadelphia Story, 1957–2013,” Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 138, no. 4 (2014): 425–56, quote from p. 426.

[4] Bauman, Public Housing, Race, and Urban Renewal, 84.

[5] Matthew J. Countryman, Up South: Civil Rights and Black Power in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006), 48–51.

[7] Kirk R. Petshek, The Challenge of Urban Reform: Policies and Programs in Philadelphia (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1973), 168.