Mantua Hall: From Tower to Square

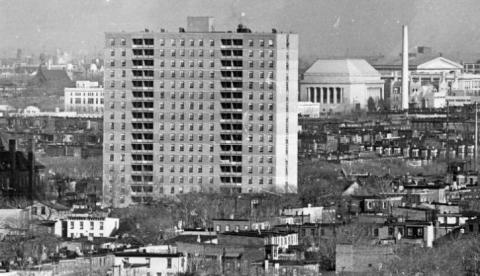

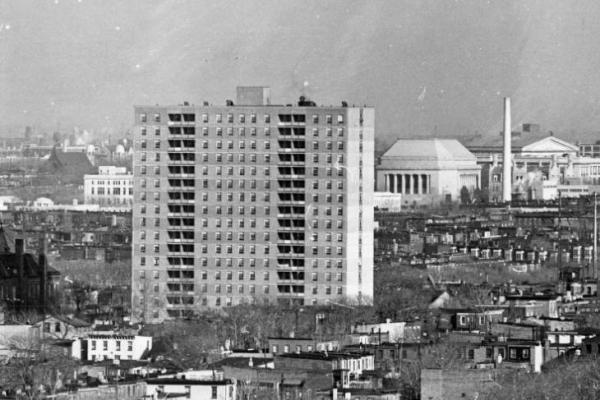

Opened in 1961 in the working-poor, black-segregated neighborhood of Mantua, Mantua Hall was an 18-storey, 153-unit modernist apartment tower built to house 495 people.

Mantua Hall, a high-rise public housing edifice, opened in 1961 in the working-poor, black-segregated neighborhood of Mantua. Located on a two-acre site on the 3500 block of Fairmount Avenue, it was an 18-storey, 153-unit modernist tower built to house 495 people. In the coming decades, it would fall prey to the social ills that vexed urban America in the half-century after World War II.

Of 5,970 new public housing units constructed by the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) between 1953 and 1961, 77 percent were built in high-rise elevator projects.[1] One of these tower projects, Mantua Hall, was located on a two-acre site on the 3500 block of Fairmount Avenue. That Mantua Hall was a segregated high-rise in a working-poor black-segregated neighborhood boded ill for the success of the project in an era of racially discriminatory housing policies.

Announced by the PHA in 1957, designed by David Howell Morgan, and opened for occupancy in 1961, Mantua Hall was an 18-story, 153-unit modernist tower built to house 495 people. Apartments included one to three bedrooms; monthly rents ranged between $33 and $85, with electricity and gas included. Each unit was outfitted with a new refrigerator, 4-burner gas range, modern cabinets, and, excepting efficiency apartments, a small screened balcony porch. The first floor housed a large community room, a laundry facility (coin-operated washers and driers), an administrative office, and maintenance facilities.[2]

Mantua Hall, like other high-rise public housing projects in Philadelphia and those in the segregated low-income neighborhoods of other major cities, fell prey to the escalating social ills and governmental deficiencies that afflicted urban America in the half-century after World War II.

Many social critics saw the steel-and-glass, poured-concrete architecture that defined multi-storied buildings like Mantua Hall as contributory to these problems—and, in the long-term, viewed it as the cause of public housing failure in the nation’s inner-cities. These commentators described high-density elevator buildings as focal points for crime and gang activity.

While this description was perhaps valid on its face, critics’ attribution of causality was misplaced. Overlooked was the burgeoning of the nation’s youth population in major cities by the mid-1960s and the “high youth densities” that housing authorities did not account for in planning the projects.[3] Unfortunately, published accounts of Mantua Hall are limited and only a deep ploughing of PHA records would suffice to tease out the youth density of this project. In 1970s, tenants were complaining about criminal youth at Mantua Hall, and according to tenants interviewed by the Philadelphia Tribune, the city’s African American newspaper, their complaints were ignored by the PHA and City Councilman Lucien Blackwell’s office.[4]

For tenants, neglected and inept maintenance was a major issue. In the summer of 1977, the Philadelphia Tribune conducted an inspection of the third, fifth, eighth, eleventh, and fifteenth floors of the building. The newspaper found the same scandalously neglected problems in apartments on each of these floors: “no fire extinguishers or firefighting equipment in the hallways. Inside the apartments . . . plaster falling from walls, doors off hinges, painted-over lead-based paint, faulty electrical outlets, and overhead sewer drains leaking into bathrooms . . . numerous holes in apartment walls providing easy entry for roaches and mice.” Tenants complained about frequently broken elevators, incinerator smoke in hallways, and “‘pitiful’” security. Complaints of violations to the Department of Licensing and Inspections dating to 1975 remained unanswered.[5]

Complaints about neglected and defective maintenance persisted throughout the 1980s. A Tribune photo caption from 1988 summed up the situation: “Mantua Hall: 18 floors and apartments full of holes.” The article dourly noted: “Mice and roaches shoot in and out of the holes, with everything but traffic cops provided for their passage between apartments.”[6]

In April 1986, in response to the city’s surging crack-cocaine epidemic and drug-related violence in the city’s housing projects, the PHA implemented “Operation Secure” at Mantua Hall, the third participating PHA project. (Twenty “major crimes” were reported in the building in 1985). Mayor Wilson Goode, who announced the Mantua version of the operation, vowed that it would “‘take control of the elevators from the drug pushers and other criminals who have terrorized our elderly and sold drugs to our youth.’” According to the Tribune, the operation was “designed to control access to the high-rise units of the three projects [the other two were Southwark and Norris] using closed-circuit audio and video equipment and a 24-hour security post staffed by housing patrol officers.”[7]

In an October 1986 article, the Philadelphia Inquirer reported on the early success of the operation, attributed to the posting of PHA security guards in check-in booths at the entrance of buildings.[8]

Yet seven years later, the Tribune declared “Operation Secure” a bust, dubbing the initiative “Operation Insecure.” Investigating the validity of the recommendation of the Citizens Crime Commission of Delaware Valley to abolish the program, which had expanded (on paper at least) since 1986 to include 17 high-rise buildings in 10 projects, a Tribune reporter was able to slip unimpeded into 10 randomly chosen high-rises across the city. The Tribune report exposed the paltry resources the PHA had to sustain the program: for example, in the event of a reported crime by a security-booth officer, “there are only four PHA police cars to patrol all 42 developments during an eight-hour shift.”[9] According to the Philadelphia Inquirer, the PHA housing police force, a total of about 140 officers, was “probably the most understaffed, poorly paid and ill-equipped police department in the area.”[10]

Throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the new Millennium, Mantua Hall’s problems persisted, perhaps most tragically evident in the death of a 19-month-old child who plunged fourteen stories to the pavement through an “unbarred window” in his family’s apartment.[11]

Throughout Mantua Hall’s troubled history, the PHA was plagued by limited resources and chronic mismanagement at the highest levels of the Authority. The situation ostensibly brightened when the PHA received a redevelopment grant from the Economic Recovery and Reinvestment Act, President Obama’s economic stimulus program, which provided funds for the demolition of the “crumbling and dangerous” Mantua Hall in 2008 and its replacement with Mantua Square—a $28.1 million PHA development, with 101 apartments for rent, built in 2011. Apartments came with income restrictions: $28,550 for one person, $32,600 for two, and $36,700 - $40,750 for three. As of late June 2019, following median rents were reported: studio, $1,230; 1-bedroom, $1,695; 3-bedroom, $1,910; 4-bedroom, $2,398.[12]

Mantua Square featured two-storey buildings with elevators for the elderly and disabled; state-of-the-art “green” technology, energy-efficient appliances, and energy-saving solar panels; a gated courtyard with parking and recreational spaces. District 3 Councilwoman Jannie Blackwell was quoted as saying, “You feel like you’re in the suburbs and you’re in the heart of Mantua.”[13]

Ironically, how beneficial Mantua Square would be to prospective renters depended on the renter’s income. Mantua Square followed a trend that began in 1995, when the PHA drew on funds from the federal HOPE VI housing program to replace some of the city’s oldest housing projects with “attractive row homes and twins, set back from the street with grass, trees, playgrounds, and off-street parking.” Such developments would be expensive, and Mantua Hall would seem to prove the new federal rule: “Perversely, in an effort to create stable neighborhoods, many families were actually too poor to qualify.”

[1] John F. Bauman, “Public Housing,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/archive/public-housing/.

[2] “Housing Authority Names 16 New Housing Projects,” Philadelphia Tribune, 30 March 1957; “$2 Million Mantua Hall Apartment Building Set to Open,” Philadelphia Tribune, 21 June 1960; Robert Eldridge, contributed to HIS 204: The West Philadelphia Community History Project (University of Pennsylvania, 2010), copy in author’s possession.

[3] D. Bradford Hunt, “Myth #2: Modernist Architecture Failed Public Housing,” in Public Housing Myths: Perception, Reality, and Social Policy,” eds. Nicholas Dagen Bloom, Frtiz Umbach, and Lawrence J. Vale (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2015), 47 – 63, esp. 56–63; in same volume, see also and cf. Fritz Umbach and Alexander Gerould, “Myth #3: Public Housing Breeds Crime,” 64–90. In the 1990s, two journalists caught the public’s imagination as to the lethality of the high-rise projects of the crack-cocaine era: For Chicago, see Alex Klotlowitz, There are No Children Here: The Story of Two Brothers Growing Up in the Other America (New York: Doubleday, 1991); for the South Bronx, see Jonathan Kozol, Amazing Grace: The Lives of Children and the Conscience of a Nation (New York: Crown, 1995).

[4] “Ignored by PHA, Seniors are Easy Prey for Youths,” Philadelphia Tribune, 19 December 1980.

[5] “Mantua Hall Tenants Cite Lack of Firefighting Tools, Leaking Sewer Drains, Lead-Based Paint,” Philadelphia Tribune, 16 July

[6] “View Between Project’s Rooms Isn’t Appreciated by Residents,” Philadelphia Tribune, 25 February 1988.

[7] “’Operation Secure’ Brings Safety to Projects,” Philadelphia Tribune, 29 April 1986.

[8] “Slamming the Door Shut on Crime at Housing Projects,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 October 1986.

[9] “PHA Housing Residents Decry Lack of Security,” Philadelphia Tribune, 15 October 1993.

[10] “The View from a Security Booth,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 4 August 1991.

[11] “19-Month-Old Toddler Falls to His Death,” Philadelphia Daily News, 24 February 1990.

[12] “Mantua Square Plans Win Award for Design,” Philadelphia Tribune,” 21 May 2010; “Officials Cut Ribbon on Mantua Square,” Philadelphia Tribune, 7 October 2011; “Mantua Square Apartments for Rent,” accessed from https://www.zumper.com/apartment-buildings/p177914/mantua-square-mantua-philadelphia-pa, 2 July 2019.