Mill Creek Homes

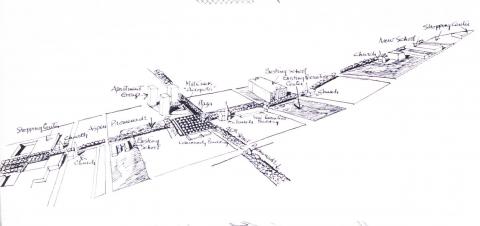

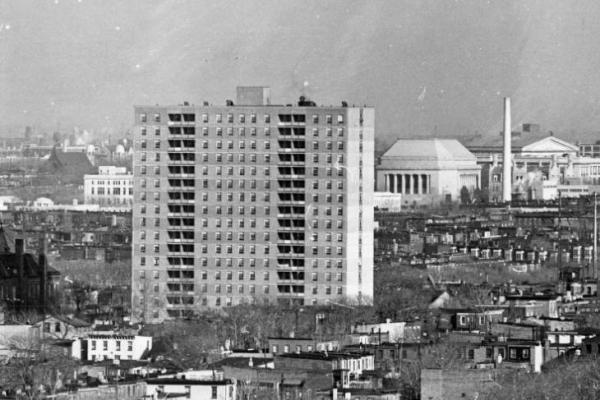

The architect Louis I. Kahn’s design for Mill Creek Homes—three 17-storey high-rise buildings and a cluster of two- and three-storey low-rises—was implemented by the Philadelphia Housing Authority in the Mill Creek neighborhood beginning in 1953 and extending into the 1960s, though with reductions in Kahn’s original design.

Mill Creek Homes, a Philadelphia Housing Authority project planned by the modernist architect Louis I. Kahn, was implemented in the Mill Creek neighborhood in a reduced version of Kahn’s original design. The project was built in two phases from 1953 into the 1960s. Its dominant feature was a complex of three 17-storey high-rise apartment buildings that loomed above Fairmount Ave. and Aspen St. east of Sulzberger Junior High School. Two- and three-storey low-rises spread out below the high-rises. Over the years, the project deteriorated in the face of poverty, crime, mismanagement, and reductions in public housing funding.

The Mill Creek neighborhood in West Philadelphia takes its name from the industrial creek that powered the textile mills north of Market Street in the mid-19th century. In the decades following the Civil War, the mills closed and the creek was enclosed in a brick-covered culverted sewer and buried under mountains of landfill. Marking the neighborhood’s transition from “countryside to streetcar suburb,” rowhouses in growing numbers occupied the former mill lands.[1] More on Mill Creek...

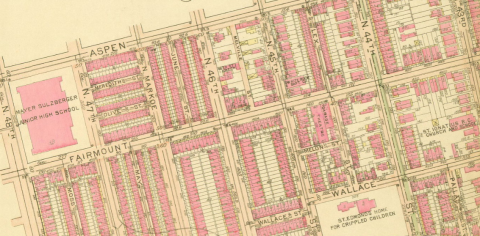

Increasingly, the occupants of these houses were African American, as a 1934 city property map shows. These houses, color-coded brown (signifying “colored”), were “redlined” by banks—i.e., rated as “low class” or “decadent,” hence ineligible for mortgage or home-improvement loans. Investors shunned neighborhoods like Mill Creek, and owners of rental properties had no incentive to upgrade their buildings.[2]

Malign neglect was not the only reason Mill Creek declined. City planners who oversaw the construction of the Mill Creek sewer, whose entry point was on the Montgomery County side of today’s City Line Avenue, could not have foreseen the extraordinary pressures that the ever-growing 20th-century “built landscape” would put on the sewer, which now had to absorb increasingly unmanageable amounts of storm water and raw sewage. The pipe, about 20 feet in diameter, was “far too small,” and during heavy downpours it would periodically rupture at weak points, destabilizing the ground under houses and causing cave-ins.[3]

In 1945, the Pennsylvania General Assembly legislated a process of urban redevelopment “to promote elimination of blighted areas and supply sanitary housing in areas throughout the Commonwealth.” (The same act authorized municipalities to create Redevelopment Authorities; Philadelphia created its RDA that same year.)[4]

In 1948, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission (PCPC) created the Mill Creek Redevelopment Area. Regarding conditions in the Mill Creek neighborhood, the biographer of the city planner and architect Ed Bacon, who directed the PCPC from 1949 to 1970, writes: “In addition to Mill Creek’s deteriorating housing stock, the land itself was in bad repair: part of the southeast section of the area was a vacant, diagonal tract where, in 1945 . . . [the] underground sewer had collapsed, destroying the homes of 135 residents.”[5]

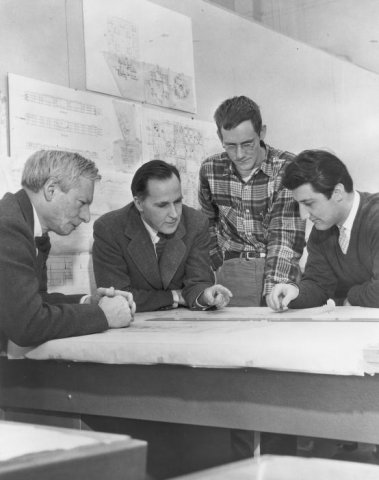

In 1951, the Philadelphia Housing Authority (PHA) invited the modernist architect Louis I. Kahn to plan a public housing project in Mill Creek. Built in two stages and encumbered by the PHA’s “very tight budget,” Kahn’s visionary plan “was reduced in scale and ambition over the years.”[6]

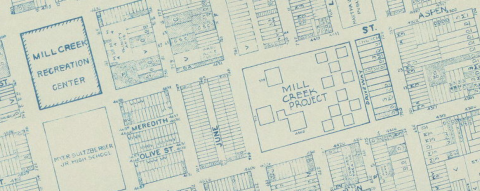

Mill Creek I, the official designation for the first stage, featured three 17-story, “modern-style” buildings at 46th Street and Fairmount Avenue overlooking a cluster of one- and two-story houses on Aspen Street.[7] Mill Creek II featured additional two- and three-story houses and a community center at 46th and Aspen Street adjacent to the extended playground of the Martha Washington Elementary School.[8]

Upon completion of phase II, the Mill Creek Homes consisted of 414 units, with 100-percent African American occupancy—a percentage that remained constant throughout the 1960s. In 1964, the total acreage claimed for redevelopment east of Sulzberger Jr. High was 11.3 acres for PHA housing construction and 2.3 acres for extending the Martha Washington schoolyard.[9]

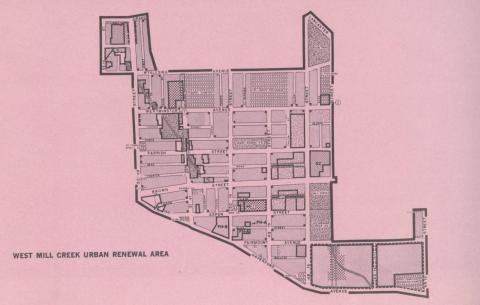

It should be noted that in 1964, planning officials mapped out an area designated as the West Mill Creek Urban Renewal Area. The URA was located west and northwest of Mill Creek Homes, which appears on the 1962 Philadelphia Land Use Map as Mill Creek Project. West Mill Creek would be redeveloped for recreation and housing conservation.[10]

[1] Anne Whiston Spirn, “Restoring Mill Creek: Landscape Literacy, Environmental Justice and City Planning and Design, Landscape Research 30 no. 3 (2005): 395–413, quote from p. 397.

[2] J.M. Brewer’s Map of Philadelphia, 1934, Map Collection, Free Library of Philadelphia. Brewer was the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company’s chief appraiser for the Philadelphia district. His detailed block-level map, printed in two sections, North and South, was used by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC), whose redlining maps were to govern the nation’s home-lending policies and practices for the next three decades. Amy E. Hillier, “Residential Security Maps and Neighborhood Appraisals. The Homeowners' Loan Corporation and the Case of Philadelphia,” Social Science History 29, no. 2 (2005): 207-233.

[3] Spirn, “Restoring Mill Creek.”

[4] Pennsylvania General Assembly, Urban Redevelopment Law, P.L. 991, No. 385, 24 May 1945.

[5] Gregory L. Heller, Ed Bacon: Planning, Politics, and the Building of Modern Philadelphia (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2013), 66. In 2002, the Philadelphia City Planning Commission introduced the 44th and Aspen Redevelopment Area Plan, which extended the eastern boundary of the original Mill Creek Redevelopment Area to include a section of the Belmont neighborhood; PCPC, 44th & Aspen Redevelopment Area Plan (Philadelphia: PCPC, 2002).

[6] Joseph Rykwert, Louis Kahn (New York: Harry N. Abrams, Inc., 2001).

[7] John F. Bauman, Public Housing, Race, and Renewal: Urban Planning in Philadelphia, 1920–1974 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1987), 114; Philadelphia Housing Authority, The City Housing Program in West Philadelphia (Philadelphia: PHA, 1960), 2.

[8] PHA, City Housing Program in West Philadelphia, 4.

[9] Bauman, Public Housing, Race, and Renewal, table 3, 172; Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, Annual Report 1964 (Philadelphia: RDA, 1964).

[10] Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority, Annual Report 1964.