Nineteenth Century Transformation: From Industrial Stream to Buried Sewer

Part of

In the early 19th century, textile mills arose along Mill Creek. The late 19th century saw the “burial” of the creek in a culverted sewer, which extended from the future intersection of City Line Avenue near 63rd Street to the Schuylkill River below Baltimore Avenue.

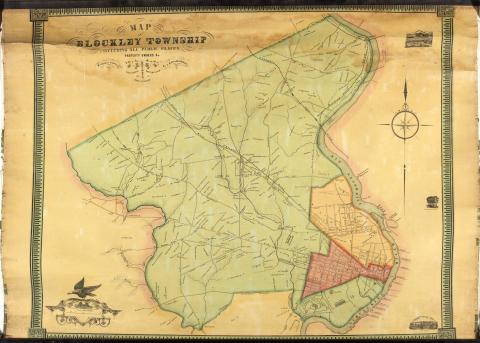

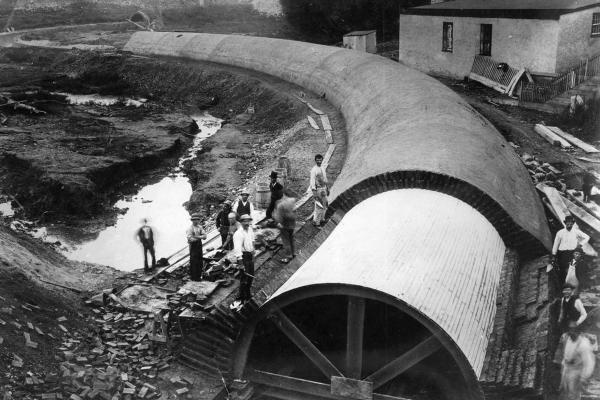

Originating in Montgomery County and entering the area that became West Philadelphia near the future intersection of City Line Avenue and 63rd Street, Mill Creek flowed southeast some five miles to its terminus in the Schuylkill River below Baltimore Avenue, near the Woodlands Cemetery. In the Colonial period, sawmills and gristmills were erected on the creek. By the mid-19th century, steam-powered textile mills were prevalent—notably John Buckman’s mill, located near the present-day intersection of 46th and Market streets. Beginning in 1869, the City moved this industrial creek, by now heavily polluted, into a culverted sewer, some 20 feet in diameter, and covered it with landfill to the level of city streets that would cross the submerged floodplain.

As historic maps of Philadelphia show, the ground beneath the City of Philadelphia, hidden far from view, is interlaced with myriad streams that flow to the Delaware or Schuylkill River. West Philadelphia’s Mill Creek is one of these tributaries.[1]

One tributary to Mill Creek originates in a spring in Lower Merion Township, Montgomery County, and still runs above ground north of 63rd and Overbrook Avenue. Once called “Nangensey” by the Lenape and “Nangenseykill” by the Dutch, the creek takes its English name from sawmills and grist mills that dotted its course in the Colonial period. From its source in Montgomery County, Mill Creek flowed southeast in bottomland through Overbrook into the village of Hestonville, where it joined George’s Run. Crossing what is today Market Street near 46th Street, the low-lying, fast-flowing stream traversed land that today forms Clark Park and emptied into the Schuylkill on the southwest boundary of the Woodlands Cemetery.[2]

In 1817, Jacob Mayland built a saw mill—and later, a snuff house—on Mill Creek south of the Baltimore Turnpike, lending his name to Maylandville, the small 19th-century village that arose near the mill, long since lost to memory.[3] In 1826, the merchant-banker John Buckman, the owner of Blockley Retreat (an estate of 240 acres acquired in 1794 by Paul Busti), built a textile mill on the creek at a point near the present-day intersection of 46th and Market streets. The mill’s waterwheel was driven by water diverted into a mill race that paralleled the creek for 350 yards. Other mills arose along the creek in the 19th century. “By the middle of the nineteenth century,” writes the landscape architect and historian Anne Whiston Spirn, “steam-powered textile mills were prominent.”[4]

Mill Creek carried a huge volume of water. It posed a serious problem for suburban development as the roiling stream occasionally flooded in no small way. In the second half of the 19th century, as City leaders began to plot the extension of the city’s grid in West Philadelphia, they decided to put Mill Creek underground, a decision that would have disastrous consequences in the 20th century.

Beginning in 1869, the City enclosed the stream in a brick-covered sewer culvert some 20 feet in diameter, ultimately burying the pipe from Overbrook to south of Baltimore Avenue by covering it with landfill up to the level of the city streets that would cross the now “buried floodplain”—a term coined by the landscape historian Anne Whiston Spirn—as much as 35 feet above the former creek bed. This project was completed in 1894.

Now part of the city’s sewer system, the underground sewer carrying Mill Creek ran southeast roughly paralleling the Pennsylvania Railroad tracks to 55th Street, where it turned more sharply southeast and flowed under Clark Park to its discharge point on the Schuylkill, on a line with 43rd Street. Mill Creek’s burial opened the floodgates (so to speak) for row house development throughout the buried floodplain. Once Mill Creek was in its tunnel, it was “forsaken and forgotten.” As the urban-watershed expert Adam Levine writes, “It is not surprising that when a section of the Mill Creek sewer near 51st and Brown collapsed in 1961—swallowing up four houses and taking three lives—it was the first time many people in the Mill Creek area of West Philadelphia learned the origin of their neighborhood’s name.”[5]

[1] Katheryn B. Harris, “Mill Creek Is Not All Bad,” Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, 27 August 1961.

[2] Adam Levine, “A Brief History of the Overbrook Neighborhood of Philadelphia, Focusing on Changes in the Natural Landscape,” accessed from http://www.phillyh2o.org/backpages/OverbrookHistory.htm, 20 July 2016; “Mill Cree“What’s Under Your Home? Take a Look at Phila.,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 11 July 1999.k (Philadelphia),” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mill_Creek_(Philadelphia).

[3] Leon S. Rosenthal, A History of West Philadelphia’s University City (Philadelphia: West Philadelphia Corporation, 1963), pt. 8; see also W. Wallace Weaver, “West Philadelphia: A Study of Natural Social Areas” (Ph.D. diss., University of Pennsylvania, 1930), 63–64.

[4] “Mill Creek (Philadelphia),” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mill_Creek_(Philadelphia); Anne Whiston Spirn, “Restoring Mill Creek: Landscape Literacy, Environmental Justice and City Planning and Design,” Landscape Research 30, no. 3 (July 2005): 397.

[5] Tello J. d’Apéry, Overbrook Farms: Its Historical Background, Growth and Community Life (Philadelphia: Magee Press, 1936), 52–54; “Mill Creek (Philadelphia),” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mill_Creek_(Philadelphia); Anne Whiston Spirn, The Language of Landscape (New Haven, CN: Yale University Press, 1998), 10–11, 161–62, 185–88, 212; Anne Whiston Spirn, “The Nature of Mill Creek: Landscape Literacy and Ecological Democracy,” In Steven A. Moore, ed., Pragmatic Sustainability (Routledge, 2016); Mark Frazier Lloyd, “112 Acres of Change in the Heart of West Philadelphia,” University of Pennsylvania Archives, http://www.archives.upenn.edu/histy/features/wphila/exhbts/inst_pa_hosp/ch1sect1.html; Adam Levine, “A Brief History of the Overbrook Neighborhood of Philadelphia, Focusing on Changes in the Natural Landscape,” accessed from http://www.phillyh2o.org/backpages/OverbrookHistory.htm, 20 July 2016.