Twentieth Century Tales from the Crypt

Part of

In the 20th century, with the development of one suburb after another, the “built landscape” of West Philadelphia deposited unmanageable amounts of wastewater in the Mill Creek sewer, which, under severe pressure, periodically overflowed and, more disastrously, collapsed.

The late-19th-century city planners who oversaw the construction of the Mill Creek sewer did not foresee the powerful demographic and economic forces that would transform West Philadelphia’s landscape in the 20th century. The filling-in of the area’s population from City Line to the Schuylkill River and the ever-growing density of the “built landscape” of housing and commercial developments put extraordinary pressures on the sewer, which now had to absorb unmanageable amounts of raw sewage and stormwater. Consequently, the sewer occasionally overflowed and sometimes collapsed, the latter disasters leaving a trail of swallowed houses, undermined streets, and human fatalities.

For more than a century, the Mill Creek sewer has been a threat to life, limb, and habitat. It is important to note that Mill Creek carries not only raw sewage but also drainage water from city streets. As housing and commercial developments (the “built landscape”) increasingly dominated land use in West Philadelphia, the watershed’s capacity to absorb groundwater greatly diminished, with overflows having nowhere to go but directly into the sewer. After heavy rainstorms, the culvert’s flow was (and still is) raging. Landscape historian Anne Whiston Spirn sketches the backdrop for the disasters that occurred in the 20th century:

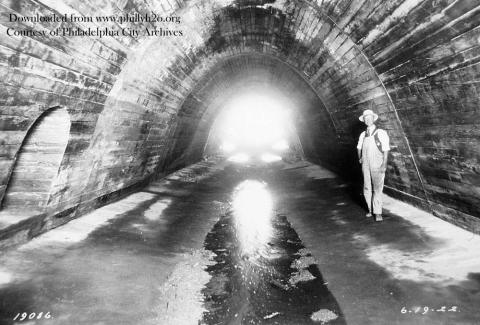

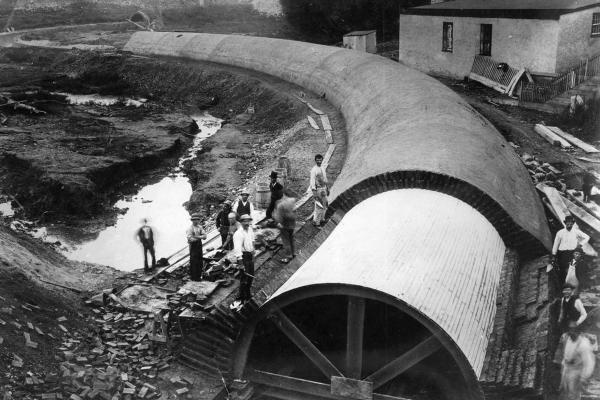

By the late 19th century, the creek was polluted by wastes from slaughterhouses, tanneries and households. In the 1880s, it was buried in a sewer, its floodplain filled in and built upon, but it still drains the stormwater and carries all the wastes from half of West Philadelphia and from suburbs far upstream. Each new suburb built in the watershed has poured more sewage and stormwater into the sewer. The size of the pipe —about 20 feet in diameter—is now far too small for the huge quantity of wastewater it must convey.[1]

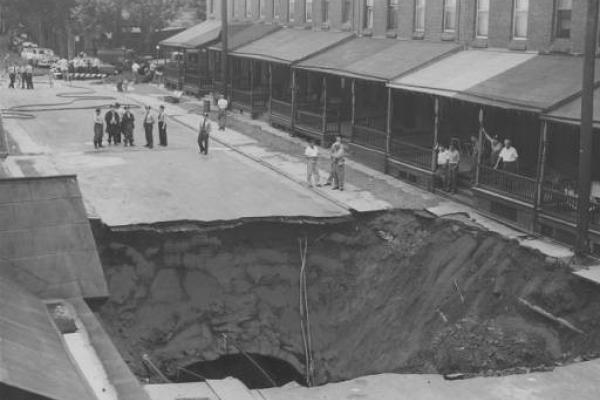

The first recorded tragedy was at 4311 Walnut Street in the fall of 1931, a house collapse that left one dead and 13 injured. Less than a year later, a Breyer’s Ice Cream truck careened into the sewer near the site of the housing collapse, though with no injuries reported. According to newspaper reports, the City shored up the damaged section of the culvert near the corner of 43rd and Walnut streets. More tragedies, however, loomed in the decades ahead.

In the summer of 1945, the City condemned houses in danger of collapsing near the intersection of 46th Street and Haverford Avenue. The summer of 1952 saw a car and a pickup truck tumble into the crater following a street collapse at 43rd and Sansom streets; several days later, as rains plummeted the area, the collapsing street unhinged front porches, resulting in the evacuation of some 300 residents. Worse was still to come: In the late evening of July 17, 1961, “there was a rumbling deep in the earth under the 50-hundred block of Funston Street . . . near the intersection of 50th and Parrish streets. By 11:00 p.m., four houses in the block had collapsed,” killing three adults and a nine-year-old boy.[2]

The City’s reconstruction (concrete reinforcement) efforts since the mid-1960s appear to have sharply reduced the likelihood of future housing collapses in the sewer’s path. Yet heavy rainstorms continue to form a raging underground river in the sewer culvert; flooding results when stormwater backs up in the street drains that enter the culvert.[3]

Today, an “interceptor” tunnel directs Mill Creek’s flow to the Philadelphia’s Southwest Sewage Treatment Plant (one of three in the city), near the Philadelphia International Airport, for treatment and discharge into the Delaware River. Excessive stormwater often overburdens this system; hence, the dire need for more and more greenspaces to absorb it.[4]

[1] Anne Whiston Spirn, “Restoring Mill Creek: Landscape Literacy, Environmental Justice and City Planning and Design,” Landscape Research 30, no. 3 (2005): 398.

[2} Stewart Windle, “Yes, There Really Was a Spring in Spring Garden. And Streams Still Flow Deep Beneath Downtown Philadelphia. But, Sometimes, the Forgotten Waters Rise . . . to Kill,” Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, 30 September 1973, pp. 31–33; “Once Quiet Stream Perils a City,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 19 July 1961; Spirn, “Restoring Mill Creek,” 395–413.

[3] “Mill Creek’s Storm Sewer Reconstruction Complete,” Philadelphia Tribune, 16 August 1966; “Maze of Buried Creeks Puts City on Shaky Ground,” Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 September 1971; Adam Levine, “From Creek to Sewer: A History of Philadelphia’s Sewers and Watersheds,” lecture presented at Morris Arboretum, 24 September 2018.