The West Philadelphia Landscape Project

Part of

Since 1987, Anne Whiston Spirn, a renowned landscape historian, first at the University of Pennsylvania, now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), has been actively involved with her students, West Philadelphia community allies, and the Philadelphia Water Department in studying the Mill Creek watershed and helping to develop reclamation and education programs in the Mill Creek neighborhood; her initiative is called the West Philadelphia Landscape Project.

Since 1987, the West Philadelphia Landscape Project (WPLP), headed by Anne Whiston Spirn, a renowned landscape historian, first at the University of Pennsylvania, now at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), has collaborated with West Philadelphia community allies and the Philadelphia Water Department in studying the Mill Creek watershed and helping to develop reclamation and education programs in the Mill Creek neighborhood. While working on a landscape design project, Spirn and her students collaborated with the urban gardener Hayward Ford and his Mill Creek community gardeners to redesign Aspen Farms, a capacious community garden built above the sewer’s landfill cover. In the late 1990s, Spirn formed a partnership with the Mill Creek Coalition to support WPLP’s Penn-student-assisted curricular projects at nearby Sulzberger Middle School, which focused on Aspen Gardens and Mill Creek’s submerged floodplain; among many other activities, Sulzberger youth worked with Philadelphia Water Department staff to build an outdoor classroom–environmental study area for the school, with a focus on stormwater management.

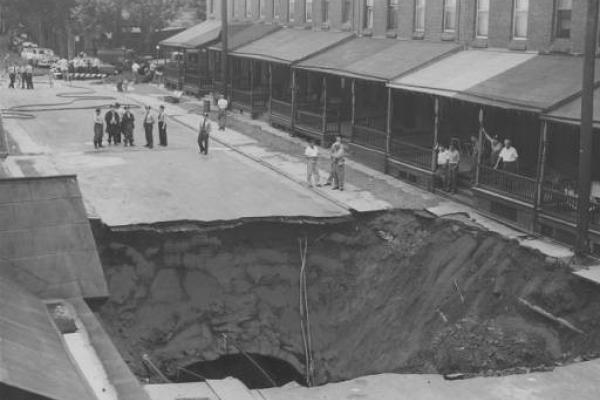

Authorized by the 1945 Pennsylvania Urban Redevelopment Act to designate neighborhoods for urban renewal, the City in 1948 created the West Mill Creek Urban Renewal Area, synonymous with the historic Mill Creek neighborhood. In 1950, the Philadelphia Housing Authority began construction of the Louis Kahn-designed, high-rise Mill Creek Housing Project near 47th Street and Fairmount Avenue. As Anne Whiston Spirn notes, “The public housing was built, as were playing fields and ball courts on other blocks that had fallen in. Land immediately over the sewer pipe was maintained as open lawn or parking lots and shifting building foundations continue to plague the area. The basement of the elementary school built on the corner of 46th and Haverford in the 1960s is frequently flooded, and the building has sustained serious structural damage.”

From the 1950s to the Millennium, the neighborhood lost all but a tiny remnant of its White population, a phenomenon thoroughly consistent with the wider region’s postwar trend of “massive migration” from city to suburb (with Philadelphia losing nine percent of its total population). The consequences were dire for Mill Creek. Spirn puts it this way: “Given the outward flow of population and capital and the inward flow of sewage and groundwater, the abundance of vacant land and deteriorating or abandoned housing in Mill Creek is not surprising. The single feature of the Mill Creek landscape that has had the most significant, persistent, and devastating effect is the least recognized: the floodplain of the creek itself and the hydrological processes that continue to shape it. And yet the strong pattern it creates—the band of open land and deteriorating buildings—is striking once recognized” (emphasis added).

Professor Spirn’s activist involvement in Mill Creek dates to 1987. In 1988–89, she and her colleague, Gary Smith, and their graduate students carried out a landscape design project at Aspen Farms. Supported by the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, Aspen Farms was created in 1975 on a site formerly occupied by abandoned buildings. The capacious urban garden was led for more than three decades by Hayward Ford. Upon his death in 2009, the Horticultural Society noted, “Hayward was one of the founding pillars of community gardening in Philadelphia. Working with the community, he put Aspen Farms at 49th and Aspen on the national map. Aspen Farms was featured in National Geographic more than a decade ago and became a place to which visitors flocked to see what community gardening was all about.” Anne Whiston Spirn and her students collaborated with Ford and his community gardeners to redesign Aspen Farms, adding a new “main street,” a pond, and a butterfly garden—the design that with the improvements periodically added by Ford became the hallmark of the project. Spirn’s initiative is named the West Philadelphia Landscape Project (WPLP).

Aspen Farms was a block from Sulzberger Middle School (today the Parkway West High School and Middle Years Alternative School for the Humanities). The Mill Creek Project, Spirn’s collaborative WPLP initiative with Sulzberger teachers, originated in 1995, with support from students in Spirn’s classes in Landscape Architecture and in Urban Studies.

The WPLP Mill Creek Project, which one teacher called “a curriculum for the millennium,” started in the fall of 1996, assisted by graduate students in Spirn’s “Transforming the Urban Landscape” graduate studio and undergraduate students in her academically based community service (ABCS) seminar “The Power of Place.” The seminar had Penn students researching local history, collecting primary documents, and designing and teaching workshops on local history and community development to Sulzberger eighth graders as part of the school’s curriculum; the coordinating teacher for the project was Glenn Campbell. The following summer, Spirn’s research assistants teamed with four Sulzberger teachers and Aspen Farm’s Hayward Ford to direct a month-long program on Mill Creek for sixth-to-eighth graders; activities included a history of the Mill Creek watershed and neighborhood, learning HTML code and website design, and urban gardening, with Aspen Farms as a real-world classroom. (The design of the project would figure prominently in Spirn’s 1998 book The Language of Landscape.)

WPLP continued to evolve as part of the academic-year school curriculum and included an after-school component; curricular emphases included local history for eighth graders (introducing them to primary sources); environmental science (trees for sixth graders, urban watershed for eighth graders), with Aspen Farms as the outdoor classroom; computer lab and math, the latter having youngsters develop a business plan and budget for a proposed Mill Creek mini-golf course. Penn student-assisted projects over a three-year period included, as the WPLP website notes, “a water park and outdoor classroom to reduce flooding and improve water quality; a miniature golf course where every ‘hole’ illustrated an event or landmark in local history; and monuments and memorials to celebrate local history.” From 1995 to 2000, Penn’s Netter Center supported WPLP research assistants and provided transportation, as well as materials for WPLP at Sulzberger.

WPLP drew national attention at the turn of the millennium: in 1999, the White House Millennium Council’s “Imagining America” cited the Mill Creek curriculum as a model of “Best Practice”; also in 1999, the project was featured on NBC Nightly News; in 2000, President Bill Clinton visited Sulzberger to learn about the project; and by 2000, WPLP’s website had attracted more than 1 million hits from some 90 countries.

In 1999, Spirn allied with Howard Neukrug, then director of the newly formed Office of Watersheds (and later commissioner and CEO of the Philadelphia Water Department), who shared Spirn’s interest in working in the Mill Creek watershed to solve the City’s combined-sewer overflow problem. Spirn and her students also allied with the longstanding community activist Frances Walker, chair of the Environment Committee of the Mill Creek Coalition (MCC), to form the MCC/WPLP partnership, which joined the Water Department in a successful grant proposal to the federal Environmental Protection Agency that focused on reducing sewer overflows from the Mill Creek watershed and funding an outdoor classroom–environmental study area for the middle school.

The Stormwater Best Management Practice Demonstration Site, at 712 N. 48th Street, was a summer project of Sulzberger Middle School students and staff of the Water Department (including a former WPLP research assistant). Supported by the Netter Center, a guidebook for this outdoor classroom, written by middle schoolers, explains the project: “Our classroom provides some of the same benefits as a natural watershed, although on a much smaller scale. In a natural watershed, rain gets absorbed into soil where it is cleaned and ultimately flows into the nearest river. Some of the rainwater evaporates in the sunlight. When roads, sidewalks, and houses are built, the water can’t go through its natural cycle, which can have a negative effect on water quality and the landscape. In our classroom, we have recreated this natural water cycle for an urban setting. When it rains, stormwater slows down as it travels through the plants to reach the drainage swale. In the swale, it takes some time to percolate through the swale before it reaches a pipe that delivers the water to the sewer in the street. Pollutants in the stormwater are also removed by the plants and swale before the water reaches the sewer. Our site holds back the stormwater during a rainstorm and cleans it before it reaches the sewer.”

In 2000, making a difficult decision, Spirn left the University of Pennsylvania to take a professorship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where she continues her involvement in WPLP. Spirn arranged for Frances Walker to receive a fellowship from the MIT’s Center for Reflective Community, and she remained a presence at Sulzberger and Aspen Gardens through her MIT courses and WPLP research assistants. The Water Department maintained its affiliation with WPLP through the EPA grant.

Two developments in 2002 undercut WPLP at Sulzberger. When the City of Philadelphia broke ground on a $110 million project to replace Mill Creek Public Housing with new homes, it did not implement the stormwater management proposals introduced by the WPLP partners. And even as Spirn and Sulzberger teacher Don Armstead, who visited MIT, were planning to continue the project using digital storytelling and the Web as tools for engaging middle schoolers, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania seized control of the School District and transferred Sulzberger to Edison Schools, an education management organization. After two key teachers, in protest of Edison School’s plans, left the school, the WPLP partnership with Sulzberger ended.

WPLP maintains its relationship with Aspen Farms Community Garden and with the Philadelphia Water Department since 2010.[1]

RELATED NOTE: A later-developing gardening initiative, the Mill Creek Farm, is separate from Aspen Farms and located two blocks north of the latter at 49th Street between Brown and Reno streets. Cultivated, like its predecessor, atop the landfill above the culverted sewer, the Mill Creek Farm is the project of the non-profit A Little Taste of Everything (ALTOE), whose mission is to “increase access to nutritious, affordable foods and provide food system education for low-income populations in Philadelphia.” Launched in 2006 with support from the Philadelphia Water Department, the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection, and the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society, the project evolved from the Penn-supported Agatston Urban Nutrition Initiative’s (AUNI) student-managed garden at University City High School, which supplied high-quality vegetables to local farmers’ markets. Former AUNI staffers decided to create the Mill Creek Farm, and they received administrative assistance from Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships.[2]

[1] For more on WPLP and its ongoing activity, see www.wplp.net, for an overview of its history, see www.wplp.net/timeline, and for stories about those engaged with the project over the past 30+ years, see http://www.wplp.net/stories/.

[2] Mill Creek Farm, https://www.millcreekurbanfarm.org/; Cory Bowman (Netter Center for Community Partnerships), personal communication, 2 October 2018.