Why Leave the South for West Philadelphia?

Part of

Southern African Americans migrated to West Philadelphia for increased economic opportunity and the potential of homeownership.

Shortly after the end of World War I, large numbers of Southern African Americans moved to start a new life in the industrial cities of the North, Midwest, and West. They left behind the shrinking number of already limited economic and social opportunities of living in a “Jim Crow” South. Philadelphia, and West Philadelphia in particular, was a terminus for Black migrants arriving from the southern states along the Atlantic seaboard. The region was an attractive location for many migrants seeking to pursue better jobs and the right to live more freely.

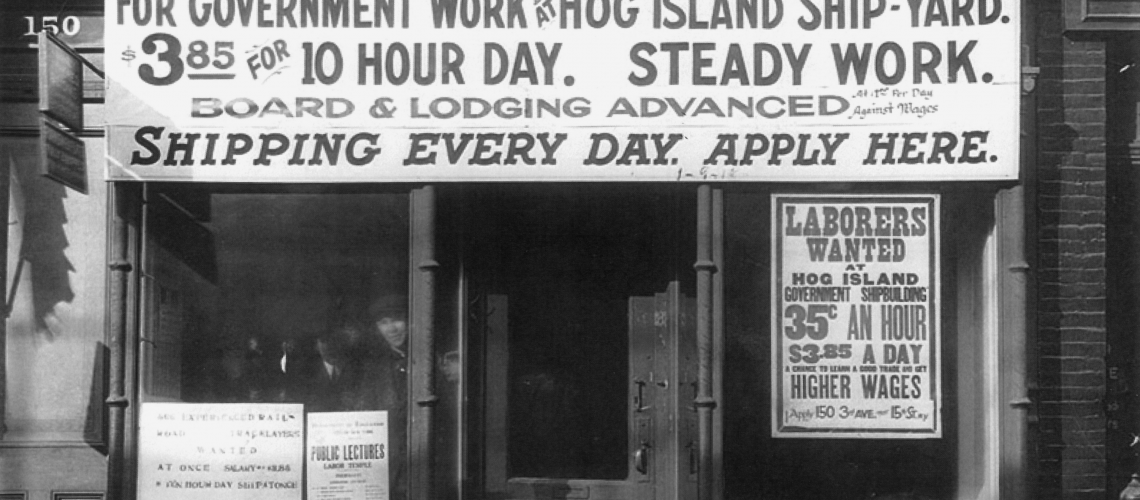

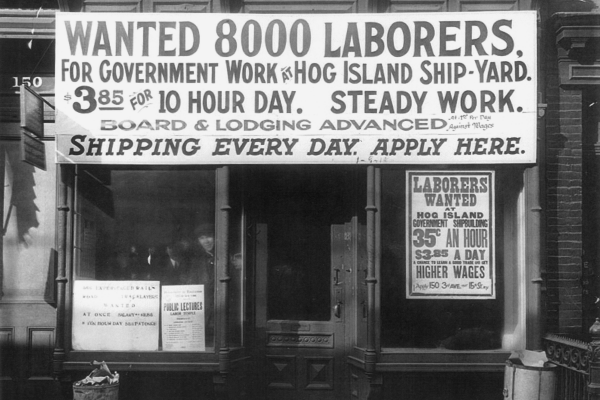

“Southern negroes are migrating to Philadelphia in increasing numbers,” reported the Negro Migration Committee in July 1923.[1] The Negro Migration Committee bore early witness to what social scientists would, as the decades rolled on, call the Great Migration. The Great Migration to Philadelphia occurred in two waves: from 1917–1918, during the First World War, and from 1920–1923.[2] Northern businesses increasingly looked to the South for labor when the overseas conflict closed off European migration, with agents from corporate enterprises such as the Pennsylvania and Erie railroads, Atlantic Refining, and Franklin Sugar luring Black southern laborers by offering jobs in Philadelphia’s industries.[3] This led to an unprecedented increase in the Black population in Philadelphia during the First World War—by the summer of 1917, more than 800 migrants arrived in Philadelphia each week,[4] with 35,000 to 40,000 southern Blacks pouring into the city between 1916 and 1920.[5] Migration in the early 1920s was greater, continuing as a result of the post-war industrial boom and southern agricultural constrictions, with arrivals peaking between 1922 and 1924 at more than 10,000 migrants per year.[6] The Negro Migration Committee—a committee formed in February 1917 by representatives of concerned private organizations—studied 931 properties, surveyed 1,292 migrants, and estimated that approximately 10,500 migrants arrived in Philadelphia between July 1, 1922, and June 30, 1923.[7] This was, they estimated, an increase of about 200% in the Black population.[8]

The migration of southern African Americans to Philadelphia was fueled by a mixture of push and pull factors. Many wished to escape the widespread discrimination that was embodied in Jim Crow race relations in the South. The executive secretary of the Travelers Aid Society noted in 1923 that the society had learned of “white activities against the negroes, particularly on the part of the Ku Klux” in the South.[9] Moreover, the boll weevil plague in southern cotton fields had spurred many farmers and laborers to leave, as seen in a survey conducted in Philadelphia in 1924 of over 500 Black migrants which reported the blight as their main reason for traveling north.[10] Four families who occupied a house at 4312 Fairmount Avenue in 1924 cited the plague as their motive for leaving the South.[11]

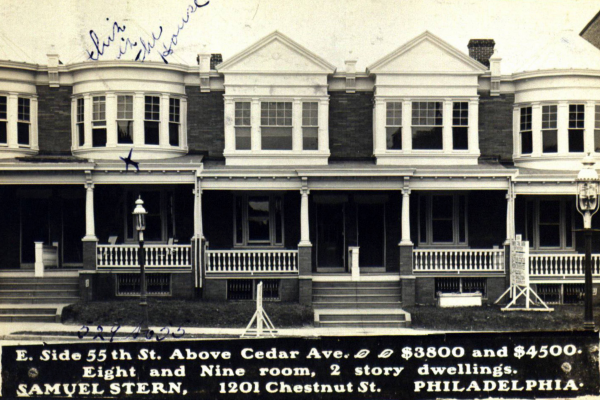

Besides these push factors, migrants were also attracted by Philadelphia’s economic opportunities. In a survey conducted by the Armstrong Association to study Black migrants, the prospect of better wages was the most cited reason for going north.[12] Southern African Americans were also enticed by home ownership opportunities in Philadelphia. West Philadelphia, reportedly the land of “sunporches, potted palms and second mortgages,” was a special attraction.[13] The Campbell family, for instance, left Savannah, Georgia in 1917 for Baltimore, before moving to Philadelphia at the insistence of Mrs. Campbell. Her son, Edgar Campbell, recalls that his mother was attracted by houses with porch fronts in West Philadelphia, and persuaded his father to move to the area.[14] Son of Black realtor Isadore Martin explained the attraction of West Philadelphia: “West Philadelphia was a garden spot and it was the newest part of the city and was considered a desirable place to live [...] If you moved to West Philadelphia you would have a porch, very often a front yard, and a back yard and perhaps a side yard.”[15]