Private Organizations Respond to the Post-War Housing Crisis

Part of

Concerned Philadelphians addressed the housing issues and discrimination faced by migrants.

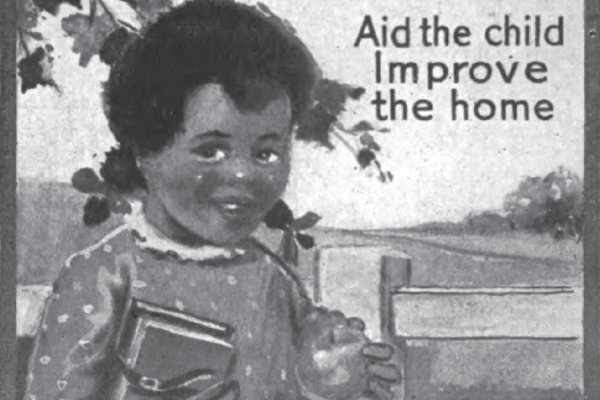

Many Philadelphians took the lead to improve housing conditions in the city. Organizations like the Philadelphia Housing Association and the Armstrong Association took measures to improve the living conditions of migrants by lobbying public officials to address illegal housing issues and attracting attention to overcrowding. They also helped coordinate the efforts of social and charitable organizations like local churches.

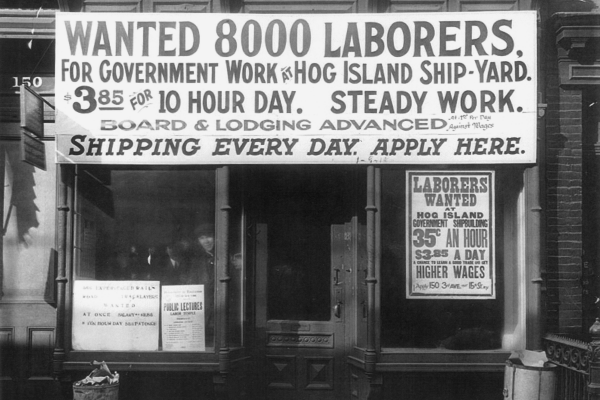

The Philadelphia Housing Association (PHA), a private, professionally staffed organization founded in 1909, undertook a range of activities to address the housing struggles faced by migrants during the first wave of the Great Migration. It surveyed housing conditions, brought sanitary and structural violations to the attention of city officials, lobbied city officials for housing code reform to address legal shortfalls, studied rent increases, and worked with welfare agencies such as The Society for Organizing Charity to alleviate living conditions among the poor.[1] Furthermore, it strove to convince the public that the migration was not inherently a racial problem by arguing that the housing crisis could just as likely have resulted from an extensive migration of Whites or immigrants.[2]

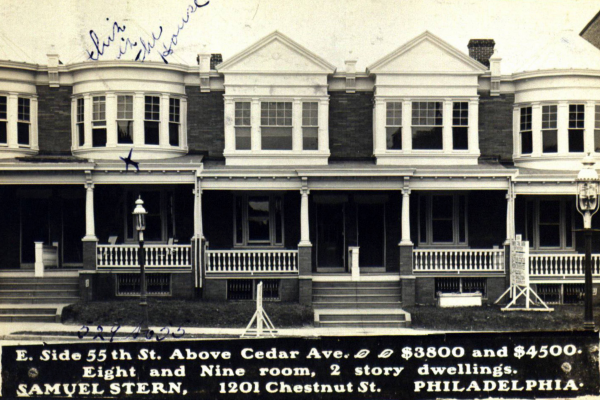

The PHA also helped to establish the Negro Migration Committee in 1917, an umbrella organization that brought together representatives of social and charitable agencies, churches, and industrial corporations such as the Pennsylvania Railroad to address issues arising from the Great Migration. Under the Committee’s first chairman, John Ihlder, executive secretary of the PHA,[3] the Committee searched for housing vacancies for migrants, helped to improve sanitary conditions, and attempted to convince builders to sell new houses to Blacks. Though it was disbanded in 1919,[4] the Committee was revived in 1923 when renewed migration in the 1920s spurred another housing crisis.

To inform and galvanize the public to address the housing problems of migrants, the Committee released a public report in July 1923 on the new migration. In the report, Armstrong Association industrial secretary A.L. Manly argued that the severe housing shortage and overcrowding in predominantly Black districts posed a danger to public health, and he advocated for more efforts to improve migrant housing.[5] When city officials failed to act, the PHA and the Armstrong Association ratcheted up publicity to pressure city officials and realtors to help ameliorate the crisis. [6]

The Armstrong Association also strove to address health issues and helped to direct migrants to social agencies and churches.[7] These efforts led to reductions in housing shortages in the mid-1920s, though the PHA cautioned that efforts to improve housing conditions should continue as long as vacant buildings were unfit for dwelling.[8]