Plays for the Local Audience

The Knickerbocker Theatre, predecessor to Fay’s Theatre, debuted in 1914, offering performances catering to the local community.

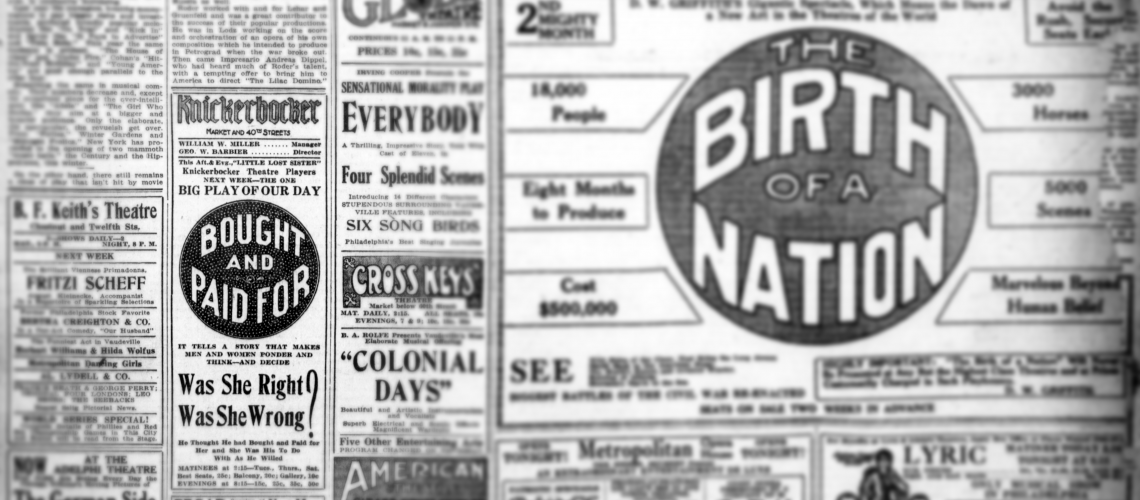

In 1914, the 2,500-seat Knickerbocker Theatre opened on the corner of 40th and Market Streets. Market Street Elevated passengers could see the marquee from the train. But its success depended on more than a good location. The theater was only one of two in the Philadelphia region with a house stage troupe at the time. The Knickerbocker Players as well as the theater depended on the local audience. Their plays often featured plots or locations appealing to demographics that reflected the population around the theater. Newspaper advertisements also targeted this white, middle-class audience. Managers did not attempt to appeal to the small but growing African American population.

Fay’s Theatre began its life as the Knickerbocker Theatre, a vaudeville house established by Marcus Loew, later of MGM fame. The 2,500-seat theater was built to be a prestige institution. Its 40th and Market Street address was a prime location, as passengers of the newly constructed Market Street Elevated could see the marquee from the train. Designed by one of the premier theater architects of the day, William Harold Lee, its beauty was praised by Variety magazine:

The walls of the lobby are lined with large mirrors and the interior scheme of decoration made up of a tasteful combination of old rose and gray, show off to decided advantage by a system of indirect lighting. […] The acoustic qualities seem excellent.[1]

Reputedly Loew spent $200,000 on construction, making the Knickerbocker the most expensive West Philadelphia theater built at the time. It’s only nearby competition was the William Penn Theatre on 39th Street and Lancaster Avenue, owned by Fred Nixon-Nerdlinger.[2]

Rapid change occurred in West Philadelphia in the decades before the construction of the Knickerbocker Theatre. The establishment of streetcars along 40th Street in the late 19th century led to waves of development and settlement in the area, eventually sprouting into a thriving commercial and residential district. South towards the primarily residential area of University of Pennsylvania, the area remained mostly residential, but some of the country’s first apartment buildings began to appear in the area. To the north was Powelton Avenue, a sleepy but soon fashionable city neighborhood.

The 1910 Census tells us a little of those who lived within a two-block radius of the theater. Much of the population was working- or middle-class Caucasians born in the United States. About 12%, a significant amount, were first generation immigrants. Even among those born in America, the area was still ethnically diverse. About 26% of native Philadelphians had at least one parent born abroad. Meanwhile, crammed in narrow roads and side streets like Ludlow or Wiota Streets were some of Philadelphia’s African American population, accounting for about 26% of the neighborhood. Segregation was a fact of life, but it was one that occurred house by house, block by block, rather than ensconcing whole areas of the city.

It was in this ethnically rich, but divided area that the Knickerbocker Theatre debuted with some fanfare September 2, 1914.[3] Despite the fact Loew billed it primarily as a vaudeville and photofilm house, the theater employed its own theater troupe, the Knickerbocker Players. The Knickerbocker Players were the only stock players in the city at this time, save for one in distant Manayunk.[4] They performed a variety of play genres popular at the time. On opening night, for example, the players debuted with Sardou’s Diplomacy, an example of the “Well-Made Play” genre where stories followed highly conventional act structures and used traditional plot devices. Other productions like Within the Law were Broadway melodramas—highly emotional plays incorporating scandalous themes for the time (in this case, a woman running a gang) that ultimately reinforced conventional middle-class moralities (the woman is wrongfully accused of crime, and her gang only commits crimes that are “within the law” to survive).[5] Mari Fielder, a historian of American theater from 1888–1930, points out that the production of plays lionizing the immigrant classes and bourgeois Christian values demonstrates how well local stock actors like the Knickerbocker Players and Mae Desmond knew their audience.[6]

Many of these plays were certainly chosen because they were popular, and individual actors and actresses like Mae Desmond received a lot of attention from the press. Audiences in the early half of the 20th century were not necessarily drawn in by celebrity culture and movie hype like today’s audiences. While no data exist on Philadelphia’s theater habits in the 1910s, some analysis has been performed on all 23 MGM theaters in the Philadelphia area during the 1930s. The data suggest that while Philadelphians went to the movies regularly, famous films and stars were not the main attraction. Instead, movie theaters were appealing because they were a cheap, local, and therefore easily accessible source of entertainment. The best theater, then, was the closest. But in an era when there might be three or four theaters within a mile of one another, how does one compete? What film genres a cinema decided to project could have been an important factor in bringing in audiences.[7]

What can these rare records from 1936 tell us about theatre watching habits at the Knickerbocker? There is some evidence that stock play audiences had similar habits, especially when movie palaces like the Knickerbocker Theatre were caught in the transition from popular theater to popular film exhibition.[8] Since the Knickerbocker was one of the only theaters in the area showing both stage performances and film, the managers could afford to cater to their preferred audience.[9] Generally, plays were chosen because they suited the sensibilities of a local audience. The Knickerbocker’s choice of melodrama and stock were aimed at a specific audience—in this case, White, middle-class West Philadelphians.[10] One telling piece of evidence is that they charged 75 cents per ticket, rather than the 50 cents that was standard for suburban stock theaters, signaling perhaps that they wanted a “higher class” clientele. Yet, as it was less than the dollar charged by many Center City establishments, it was still considered to be “popular pricing,” as it was termed during the time.[11]

The melodramatic stock plays the Knickerbocker Players exhibited weren’t the only efforts Loew and Meyers put into appealing to the local community. Many of the plays featured settings that first and second generation audiences would recognize and enjoy. Irish community members appreciated the regular appearance of Irish-American actresses like Mae Desmond and the Irish settings of plays like Undercover and Paid in Full. Members of the small, but prominent Jewish community were also represented well on stage, with plays like The Yellow Ticket valorizing the bravery of Jewish women in Russia during the turn of the century. The Knickerbocker Theatre’s advertisements in Jewish newspapers like The Jewish Exponent show that the Jewish community was a valuable market for the theater.

Audiences were also courted directly by the Knickerbocker Players. Audience connection was crucial for the troupe to survive financially. Attracting and keeping an audience involved curating a loyal following. The players went out of their way to forge bonds with the audience outside of performances. The Knickerbocker Players were well-known for their public receptions and free souvenirs.[12]

Why did they do this? Although vaudeville and stock theater still could attract audiences in 1918, its glory days were over. Philadelphia Evening Bulletin theater columnist Henry Murdock noted that Philadelphia theater peaked in the 1880s during the height of popularity of the minstrel show, with numbers declining steadily after that. Productions fell to less than 100 by the 1925-1926 season, and then to less than 30 by 1940.[13] Being able to attract and keep an audience, then, involved cultivating a loyal following. Fielder argues stock groups like the Knickerbocker Players, and later the Mae Desmond Players, could overcome economic difficulties because they connected with their audience so closely. Both groups obtained a moderate fan base and achieved financial stability for relatively long periods (three years and fifteen years respectively). Audiences saw themselves in these actors. One recalled enjoying their shows so much because, “They’re just like us!”[14]

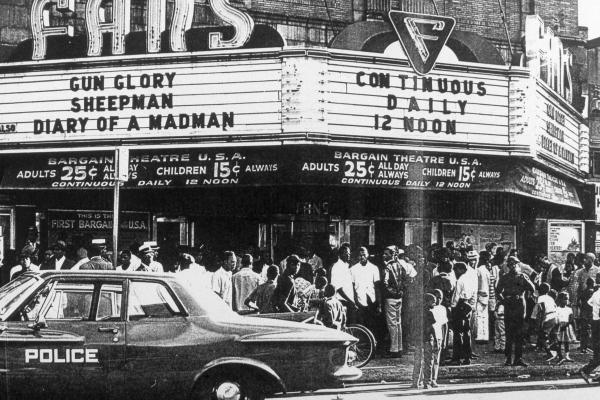

But the Knickerbocker did not target all demographics of the community surrounding the theater. According to the 1910 census, more than a quarter of the population in a two-block radius of the theater was African American. No effort was made to attract this audience. The Knickerbocker usually placed its ads in mainstream publications like the Philadelphia Inquirer, or even immigrant newspapers like the Jewish Exponent, but none appear in African American newspapers like the Philadelphia Tribune. The lack of advertising only suggests the greater truth—the Knickerbocker was well-known as a Jim Crow establishment across the state of Pennsylvania. In 1935 a Pittsburgh columnist reflected on the reputation of the Knickerbocker (at that time called “Fay’s”):

Fay’s enjoyed a malodorous reputation first as the old Knickerbocker and later as Fay’s, for it was known among our people as a nasty jim-crow hole—one of the nastiest in West Philadelphia. For that reason very few colored people ever saw inside the building.[15]

Despite the success from managers and performers catering to (part of) the local community, revenues were not enough to fight the end of the stock theater troupe, and the Knickerbocker Players’ position on 40th & Market Street proved to be precarious. Acting rosters were particularly unstable, and performances became more and more irregular. Loew turned to more reliable bookings like film and independent vaudeville acts. Their comparative stability made paying a stable of regular actors undesirable. The players disbanded as a result in 1918. Loew sold the theater to Edward Fay only one year later.[16] Fay, based in Providence, Rhode Island, owned a chain of theaters. He renamed his new Philadelphia purchase, “Fay’s Theatre.”

Fay knew something had to replace stock theater. The loss of the troupe’s performances of live stage plays meant the Knickerbocker was no longer unique. It was now in direct competition with nearby theaters like the William Penn Theatre on 39th Street and Lancaster Avenue and the Eureka Theatre on 39th and Market Street. Both had a similar lineup of films and vaudeville acts.

Fay’s managers tried a variety of performances and publicity stunts tailored to appeal to the same type of audience that had come for the Knickerbocker Players. One notable example was advertising a boxing match within the theater on December 8, 1924.[17] This was highly unusual for theaters of this period. Given the popularity of boxing matches among working- and middle-class immigrant families in Philadelphia, there is little doubt that the managers believed the match would attract a local audience.[18] The event received little fanfare, suggesting the match proved unsuccessful. Another popular attraction that the managers of the Fay tried to implement was magic. Magic shows reached their height in America in the late 1920s and early 1930s with escape artists like Harry Houdini capturing national attention. A big appeal of booking a magic show is they almost always incorporated a publicity stunt as part of the act. For example, King Brawn used the roof of the theater to stage an escape from a “Spanish torture chamber,”[19] which Fay’s managers must have thought would attract passersby.

Twelve years after Fay’s purchase, the theater perpetually underperformed. The managers were not successful in their attempts to court the audience that made the theater a success before 1919. Fay, facing difficulties with even his most profitable Rhode Island theaters, sold the 40th and Market location in 1931.