Jazz at Fay’s

Fay’s Theatre found success as a jazz club after managers expanded their target audience to reflect West Philadelphia’s changing demographics.

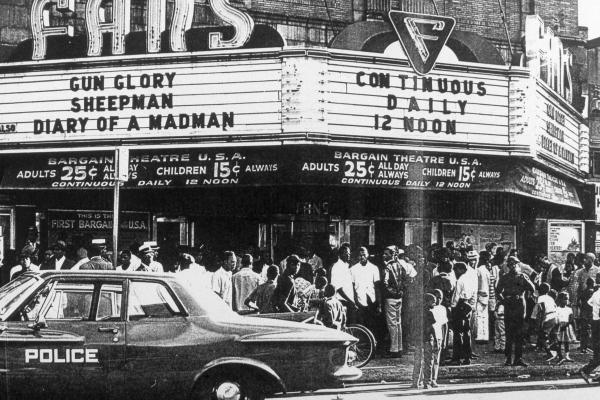

After years of struggling against local competition, Fay’s Theatre’s new managers dramatically shifted its target audience to include the rapidly increasing population of African American residents. In September of 1931, it reopened as a segregated theater for African Americans. White residents reacted poorly, forcing the theater to remain open to all, with Black patrons only welcome in the gallery. Still, the symbolic identity of the theater changed, leading the way later for Shep Allen to make Fay’s into a well-known Philadelphia jazz hotspot. Even through periods of financial difficulty, Fay’s maintained excellent relationships with musicians from Ella Fitzgerald to members of Philadelphia’s local Black musicians’ union.

By 1931, Philadelphia theaters were struggling in the midst of the Great Depression. Many shuttered due to financial difficulties. Fay’s Theatre, a small movie house and vaudeville stage on 40th and Market Street, had already been struggling for more than a decade following the loss of their house stage troupe in 1918. The troupe’s stage plays drew in a loyal local audience, due largely to the fact that the theater catered to a White middle-class audience that matched a large percentage of the population surrounding the theater in the 1910s. Managers tried and failed to re-engage this audience throughout the 1920s with a variety of novel acts and performances.

Wax Interests took a different approach when they leased the theater in 1931. The company specialized in African American theaters across the Philadelphia region.[1] On September 16, 1931, Fay’s reopened again, and this time it was for “Negros only.”[2]

The change of audience reflected a larger demographic shift that occurred in Philadelphia since the Knickerbocker Theatre (which became Fay’s Theatre in 1918) opened in 1914. In the aftermath of World War I, with immigration sharply curtailed, the city’s factories found themselves without their traditional source of cheap labor. African Americans filled the gap, migrating north in vast waves in what has since been called the Great Migration. The African American population in Philadelphia had doubled between 1900 and 1920, from 63,000 to 130,000.[3] The demographic shift was evident within the immediate vicinity of Fay’s.

Though the overall population decreased between 1910 and 1940 in the two-block radius surrounding 40th and Market Streets, the population of African Americans grew by about 60%. African Americans—previously a small percentage of the population only occupying narrower streets like Ludlow and Filbert—made up about 46% of the general population in 1940.

For African Americans in these blocks and throughout the rest of West Philadelphia, Fay’s Theatre was the only theater option without traveling into Center City. Other theaters catering to African Americans existed—most notably Shep Allen’s Pearl Theatre near Temple University and the Royal Theatre on Broad and South Streets—but these were far away and required, at the very least, the use of public transit. Fay’s would have been the only theater of its kind in West Philadelphia at the time.[4]

In a progressive and unusual move by management, all of the theater’s staff was Black. Philadelphia Tribune columnist Randy Dixon described the rarity of this kind of staffing:

It is completely manned by Negro labor. Stage hands, electricians, managers, ushers, usherettes, cashiers, orchestra, machine operators are all Negroes. Though I never attempted to investigate, I daresay this condition does not obtain at any other local theatre, which I might also say or be told is none of my damn business.

[…]

Don’t spend your money where you can’t work, has been adopted this slogan and applied it to the amusement field bank-and the result of their fight has justified the battle. If the public adopted this slogan and applied it to the amusement field, bankruptcy would overcome many so-called colored theatres.[5]

Converting to a “Negro-only” theater made financial sense. Fay’s fought nearby theaters and vaudeville houses for White audiences. Converting to what was a dramatically underserved audience at the time eliminated that struggle. However, conversion from a White theater to a Black theater created backlash from the local White community, leading to a series of events later called the “Fay’s Theatre Fiasco.”

While the theater opened with great fanfare on September 16, 1931, it was closed only three days later, and a new policy was announced. African Americans, the patrons making up the “bulk of the patronage” would only be seated in the gallery. This change of heart was in response to the show of force of the all-White 40th Street Business Association. Some leaders of the association reportedly went as far as to assault the Fay’s manager, Joe Wood, a well-regarded member of Philadelphia’s African American entertainment scene. The 40th Street Business Association disavowed any knowledge of the violence, but did not deny they had requested that the theater remain “open to all.” Speaking in defense of himself and his organization’s actions, the treasurer of the 40th Street Business Association, E. Humburger, said, “I do not call that discrimination” and “they do it in all the downtown theatres – and they tell me that they pack them in!”[6]

African American newspapers reported public outcry over the Fay Theatre Fiasco as far away as Baltimore, where it was reported in the local Afro-American. The Philadelphia Tribune made it a front-page story. Local African American women, led by Rose Satterwhite, created an organized effort to boycott businesses on 40th Street.[7] Isadore Martin, a West Philadelphian, and prominent Philadelphia NAACP leader, lauded her actions. Martin then stressed “that the theatre should be opened as a playhouse for all the people and that Negroes should be able to sit where they pleased.”[8]

After the fiasco, the lights at the Fay fell dark. The lease was turned over to Edward Fay again briefly and experienced a moderate amount of success. It did not experience real renown until it reopened with a new manager, Shep Allen, on August 2, 1935. The night’s headliner was Louis Armstrong. Allen, well-respected manager of Washington DC’s Howard Theatre and Philadelphia’s Pearl Theatre, would shape Fay’s into a notable Philadelphia jazz venue. More star power followed, due to Allen’s connections with prominent jazz musicians. It attracted the greatest jazz stars of its day, from Ella Fitzgerald to Duke Ellington, to Count Basie and his Orchestra.

In its jazz heyday, Fay’s served as a symbolic place for local African Americans, if not a literal one. Fay’s booked performers like Duke Ellington—popular and highly visible members of the larger African American community—who were part of an emerging Black identity evolving in the African American press. Part of the emerging identity was a deep concern with issues of developing critical citizenship, fighting oppression, and gaining civil rights.[9] Fay’s Theatre embodied this, having been dedicated to Florence Mills, who was remembered by the Philadelphia Tribune as a Black singer whose success in the mainstream allowed other Black musicians to succeed.[10]

Fay’s also maintained a friendly and equitable relationship with local Black musicians. Fay’s often included performances by the Local 274, members of an African American musician’s union, created to protect its members from the unethical and racist behaviors of many theater owners across the city. They performed there frequently.[11] Famously, during a musicians’ strike in 1935 when most of the musical venues in the city went dark, shows at Fay’s kept going, thanks in part to their willingness to raise worker wages in accord with the requests of the Local 274.[12]

The theater’s function as a community space was not solely tied to its use as an entertainment venue. On more than one occasion, it also hosted church gatherings. When Mount Pisgah Episcopal Methodist Church on 41st Street and Spring Garden Avenue burned down six months after opening in 1942, church members were invited to hold services at Fay’s for the duration of reconstruction.[13] The decision was largely a practical one. The theater, with more than 2,000 seats, could easily accommodate a church congregation. However, Fay’s temporary use as a church meeting place also speaks to its acceptance by the local community. The theater, although an unorthodox choice for a traditional church service, was not ultimately seen as an inappropriate venue even though by 1942, striptease acts were regularly featured.

It’s not clear when striptease acts started at Fay’s, but by the 1940s, these performances were in full swing, part of a national trend where such acts were incorporated into the nightclub scene.[14] It is easy to imagine that such nightclubs were the purview of only men as they often are today, but that would not be entirely correct. Nightclubs had become a more legitimized establishment during the 1930s and 1940s, thanks to the repeal of Prohibition and their glamorization in Hollywood films. During World War II, nightclubs were most often frequented by soldiers on shore leave, but women, whether they were secretaries or factory workers, also made up a sizable minority of the audience.[15] Profit largely drove the incorporation of striptease acts.

Fay’s was one the main destinations for striptease in Philadelphia, in company with two Center City establishments, the Trocadero Theatre and Carroll’s Cafe. Their notoriety drew the attention of city officials when Philadelphia cracked down on stripping in 1942. Philadelphia had become a mecca for striptease after a similar ban in New York City a few years before. Church and reform groups took their concerns to recently elected mayor, J. Hampton Moore, who campaigned with promises of reform. On April 7, a few short months after offering to host Mt. Pisgah’s church services, Fay’s, along with Carroll’s and the Troc, was raided by the police. The manager, one co-owner, and three performers were arrested on charges of “promoting an indecent show.” Police said Fay’s had been the subject of complaints from school officials. Acts, aside from striptease, catered to families and their children.[16]

In the wake of media coverage following the raid, Fay’s pledged to completely remove striptease acts from their stage. Without the usual lineup of “a variety act featuring two or more strippers, plus a Class B picture,” business dropped off dramatically. Just two weeks after the raid, the theater closed early for the summer.[17] That November, Fay’s returned to featuring bands as their headline attraction—with a focus on African American swing aggregation.[18] Some of the theater’s most memorable jazz bookings occurred throughout the following year, including a week-long return of Ella Fitzgerald and her 4 Keys starting on March 26, 1943.[19]