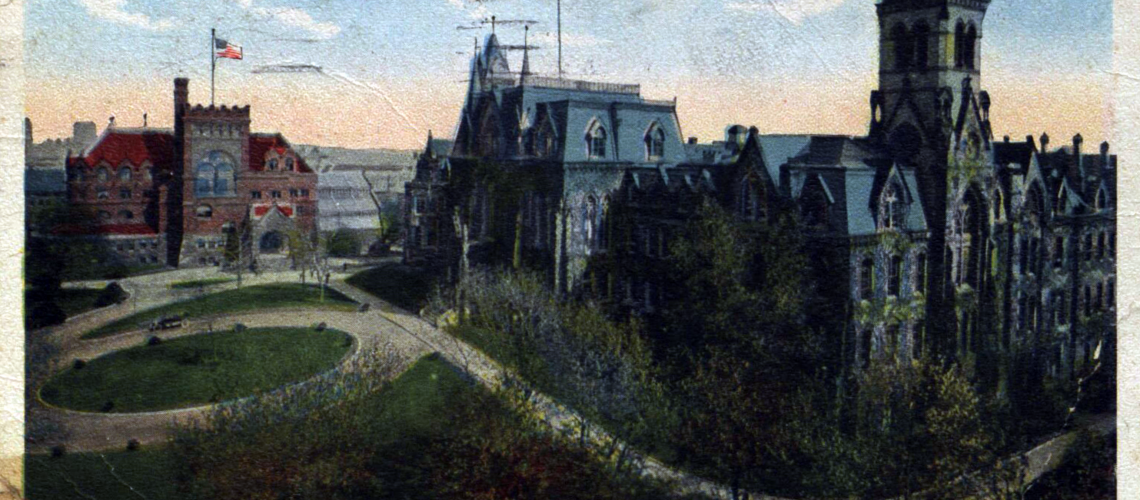

Postmarked on August 25, 1916, this postcard foreshadowed the next century of expansion when describing the University as a place "where some 30 buildings have been erected and are constantly increased."

The University of Pennsylvania in the 20th and early 21st centuries was shaped in no small way by social and economic conditions in West Philadelphia.

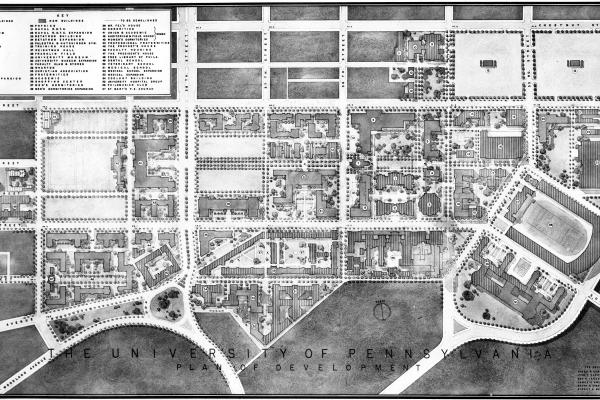

In 1913, architects at the University of Pennsylvania produced the institution’s first campus master plan, which forecasted Penn’s development as a pedestrian-oriented enclave within but separate from West Philadelphia. in 1948, when the University was physically integrated into the city, intertwined with trolley lines and city streets, and impinged upon by declining neighborhoods west of the Schuylkill River, a new generation of architects revived the idea of a parklike campus and linked their conception to the city’s plan for urban renewal. Penn built its modern campus after World War II with federal, city, and state urban renewal dollars. University-based urban renewal was not fully completed until the early 2000s. By the end of the Millennium, the University’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships had begun to repair Penn’s relationship with the wider West Philadelphia community.

Stories in this Collection

1913–1948 The 1913 Cret Report, Penn’s first campus master plan of the twentieth century, foresaw urban congestion which, if left unabated, would jeopardize the University’s future. Thirty-five years later, as industrial congestion and trolley and vehicular traffic weighed heavily on the campus, a new campus Plan, the Martin Report of 1948, echoed the Cret Report, calling for the removal of the Penn trolley lines and street closings to create an enclaved green-space campus. |

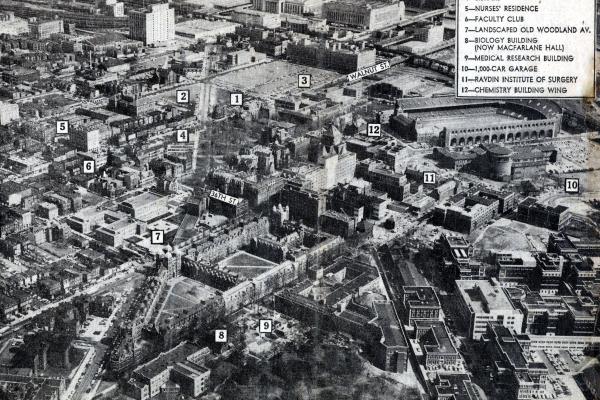

1952–1970 In the 1950s, Penn’s campus planning was closely aligned with the City Planning Commission’s urban renewal plans for the University Redevelopment Area. The City first built a subway-extension tunnel and located the Penn trolleys underground; next, upon acquiring Woodland Avenue from the Pennsylvania General Assembly, the City deeded the roadbed to Penn. Near the end of the decade, the University acquired two urban renewal planning units from the Redevelopment Authority, then split one of them with the Drexel Institute of Technology. |

1948–1977 In the 1960s, Penn’s campus expansion west and north of the historic core around College Hall was served through the eminent-domain activity of the Redevelopment Authority in Unit 4. The University received urban renewal building funds from the Pennsylvania General State Authority and the state’s Higher Education Facilities Authority, the latter agency helping to build the West Campus’s superblock of high-rise dormitories. Section 112 of the Federal Housing Act of 1959 gave urban universities wide latitude to redevelop commercial properties in the immediate campus area—in Penn’s case, Walnut Street. |

1957–1964 Alarmed that the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority (RDA) earmarked all of University Redevelopment Area's Unit 1 for the University of Pennsylvania’s campus expansion, Drexel Institute of Technology’s president James Creese filed a grievance with City Council in 1957. The RDA’s coupling of Units 1 and 2 would have given Penn urban renewal rights to the entire quadrant bounded by Walnut and Chestnut from 32nd to 34th Streets. Under pressure from City Council, Penn reached an agreement with Drexel that divided Unit 1 between the two institutions, giving Drexel redevelopment (i.e., campus-expansion) rights to Unit 1B, and positioning the Institute cheek-by-jowl with Penn. |

1958–1970 In the late 1960s, the West Philadelphia Corporation, a non-profit coalition of West Philadelphia “higher eds and meds” and a surrogate for the University of Pennsylvania, redeveloped RDA Unit 3 in the Market Street area and recruited the University City Science Center to fill the core of the unit. That large-scale project and the Science Center’s proposed affiliate, University City High School, necessitated the leveling of a working-poor, majority African American neighborhood known locally as the “Black Bottom” and displaced its residents. Penn’s role in the Science Center severely damaged its community relations for decades to come. |

1970–1990 Penn’s alienation and drift away from West Philadelphia began in the 1970s, when the University experienced turbulent campus politics, confronted a severe budget crisis, and lacked both the funds and the will to help restore its frayed community relations. At the same time, Penn faced an unprecedented rise in violent crime on the campus and its peripheral streets. This situation only worsened in the 1980s with the onset of West Philadelphia’s crack-cocaine epidemic. |

1996–2006 Between 1996 and 2002, the University of Pennsylvania, under President Judith Rodin, implemented the West Philadelphia Initiatives. This multipronged, proactive strategy, unprecedented for an American university, included innovative programs in five areas deemed essential for stabilizing social and economic conditions in Penn’s neighborhood of University City: neighborhood safety and cleanliness, housing stabilization and reclamation, neighborhood retail development, West Philadelphia purchasing and hiring, and public education investments. |

1985–2019 Penn’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships has worked since 1992 to improve Penn’s community relations in West Philadelphia in ways that harness the strengths of both the University and its community partners. Two core strategies are directed toward building mutually beneficial, democratic university–community–public school partnerships. Academically Based Community Service (ABCS) engages Penn students and faculty from multiple schools and departments in numerous academic courses that participate in mutually organized problem-solving activities with teachers, school administrators, and community leaders. University-Assisted Community Schools (UACS) is a mutually organized strategy to transform local public schools as catalytic hubs for community education and development. |