Woodland Avenue and Creating Penn’s Pedestrian Campus

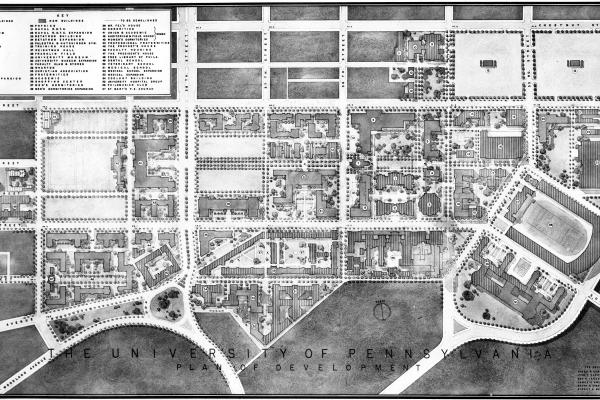

In the 1950s, the City facilitated Penn’s plans to create its modern pedestrian campus by putting the Penn trolleys underground and deeding the footprint of Woodland Avenue to the University.

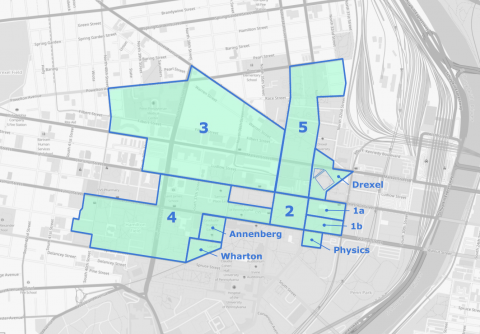

In the 1950s, Penn’s campus planning was closely aligned with the City Planning Commission’s urban renewal plans for the University Redevelopment Area. The City first built a subway-extension tunnel and located the Penn trolleys underground; next, upon acquiring Woodland Avenue from the Pennsylvania General Assembly, the City deeded the roadbed to Penn. Near the end of the decade, the University acquired two urban renewal planning units from the Redevelopment Authority, then split one of them with the Drexel Institute of Technology.

The Martin Plan was commensurate with the post-war City Planning Commission’s plan for urban renewal in an eighty-block area of West Philadelphia, designated in 1948 as the University Redevelopment Area. The alignment of the two plans was not coincidental, as the chairman of the City Planning Commission was the venerable Penn trustee Edward Hopkinson, Jr., a perennial powerhouse in city politics and a devoted alumnus of the University. The nexus that joined the two plans was the “joint Planning Commission–University transit plan,” designed to put the Penn trolleys underground.[1]

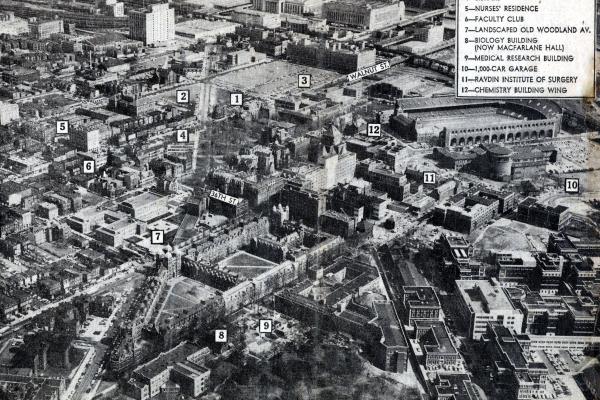

Before a tunnel for the trolley lines could be built under the Penn campus, the city had to complete a transit project it had started in 1930, but discontinued until 1948 because of the Great Depression and World War II: moving the Market Street Elevated service underground from the Schuylkill River to 45th Street. Completion of the subway-surface tunnel set the stage for the next phase of urban renewal at Penn: closing Woodland Avenue. From the mid-1950s until the end of urban renewal in 1970, the University, the Office of the Mayor, and the City Planning Commission formed an interlocking directorate. The main actors were the University’s president, Gaylord P. Harnwell,; the city’s Democratic mayor from 1956 to 1962, Richardson Dilworth; and, in a dual role, the dean of Penn’s School of Fine Arts and chairman of the City Planning Commission, G. Holmes Perkins. Planners from Penn and the city successfully lobbied the Pennsylvania General Assembly to remove Woodland Avenue between 34th and 37th Street—in the heart of the Penn campus—from the state highway system and to convey ownership of the roadbed to the city. The city in turn transferred its title to Penn. On 11 January 1958, a ceremony held in the center of the campus celebrated the closing of the avenue and the opening of Woodland Walk (which would not be landscaped until the 1970s).[2]

Twenty-one buildings owned by Penn since the 1920s occupied a trapezoidal space along Woodland Walk. By the 1950s, these buildings housed small businesses, a Horn and Hardart cafeteria, University administrative offices, and a handful of fraternities. By the end of decade, the buildings were demolished and the merchants and fraternities were relocated to make way for the construction of Van Pelt Library (est. 1962) and Dietrich Graduate Library (est. 1967). In the late 1950s, Penn was earmarked to receive a swath of properties the Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority designated as Unit 1 and Unit 2 urban renewal zones—four rectangular blocks bisected by Woodland Avenue from Walnut to Chestnut Street between 32nd and 34th streets. Penn’s entitlement to Unit 1, which bordered on the Drexel Institute of Technology (now Drexel University), was hotly contested by Drexel’s president, James Creese, and eventually those blocks were awarded to Drexel. The Redevelopment Authority used its power of eminent domain to condemn and purchase the densely-packed properties in the two units, which included dilapidated houses, a shady hotel, and low-end commercial establishments. Here the owners, willingly more or less, sold their properties to the RDA, with the unfortunate people who rented their buildings left to fend for themselves elsewhere.[3]