Planning the Modern Research University

Part of

In the first half of the twentieth century, two campus plans—the Cret Report of 1913 and the Martin Report of 1948—called for the creation of a pedestrian campus free of urban congestion.

The 1913 Cret Report, Penn’s first campus master plan of the twentieth century, foresaw urban congestion which, if left unabated, would jeopardize the University’s future. Thirty-five years later, as industrial congestion and trolley and vehicular traffic weighed heavily on the campus, a new campus Plan, the Martin Report of 1948, echoed the Cret Report, calling for the removal of the Penn trolley lines and street closings to create an enclaved green-space campus.

In 1913, The University was on the precipice of staying “a small local institution" or becoming "a nationally recognized institution.”[1] Penn ranked among the largest American universities—despite its mostly regional student body—and was just gaining a foothold in the notable list of research universities that included Harvard and Yale. College attendance was gaining popularity for the American youth due to the increased numbers of high school graduates from the middle class. Penn’s further campus expansion seemed inevitable given their growing clout and the potential for increased numbers.[2]

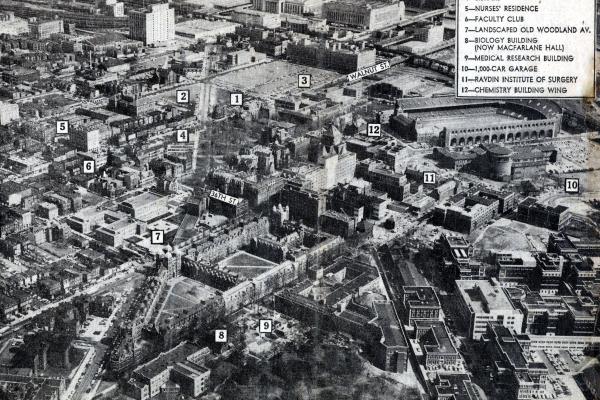

The 1913 campus master plan, known locally as the Cret Report, named after the lead planner, the famed beaux arts architect Paul Philippe Cret, revealed the harmful effects of congested traffic conditions on the campus, which, if not abated, would jeopardize the University’s future. The Cret Report called for an enclaved pedestrian-oriented campus, to be initiated, as one proposal in the report had it, by routing the city trolleys on Woodland Avenue at Penn into a subway tunnel underneath the campus, to exit at a portal near the Woodlands Cemetery.[3] A generation of post-World War II city planners would finally implement this proposal on Penn’s behalf. In the meantime, Penn’s physical campus suffered from the presence of “congested rail yards, smokestack industries, and ramshackle buildings” on its eastern boundary. Martin Meyerson, a famous urban planner and future Penn president, recalled a visit he made to the Penn campus in 1940, a locale he described as “dreary.” A major factor, perhaps the key element, in this “dreariness” was “the raucous thoroughfare of Woodland Avenue, a noisy laceration through the heart of the campus.” Writing in the 1960s, David Goddard, a Penn provost, recalled his impression of the physical campus when he first arrived in 1946:

The physical facilities were inadequate and their maintenance was poor; little construction had occurred in the last three decades. . . . Trolley cars clattered by so loudly that often lecturers in College and Bennett halls had to pause to wait for the racket to subside. Old factories, hotels, and run-down houses threatened to engulf the neighboring community.[4]

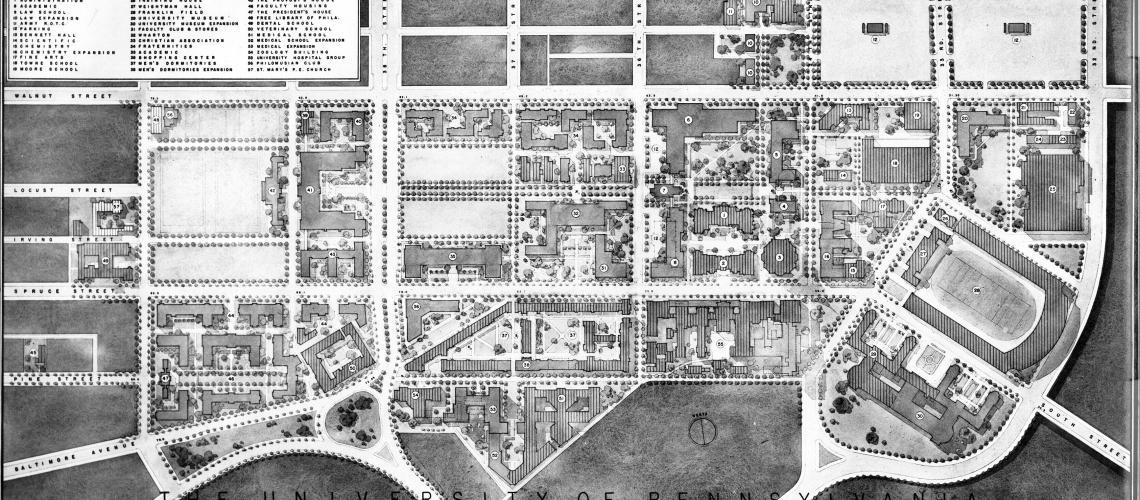

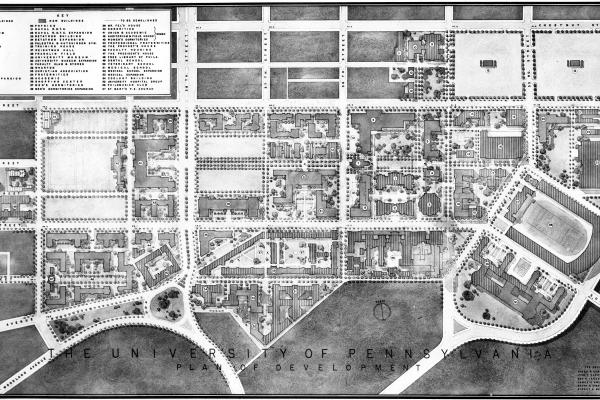

Shortages and exigencies imposed by World War I, the Great Depression, and World War II stymied the development of a pedestrian campus and necessitated a new campus master plan, which was published in 1948. This was the Martin Plan, named after the Philadelphia beaux arts architect Sydney Martin, who chaired the trustee committee that drew up the plan. The Martin Plan revised and updated the Cret Report. Paul Cret and his associates had envisioned the campus as a green-space pedestrian mall enclosed by buildings and extended on a south–north axis from College Hall and Woodland Avenue to Chestnut Street via ramps above the streets. In contrast with the Cret Report, the Martin Plan called for campus expansion on an east–west axis. The new plan envisioned rerouting the Woodland Avenue trolley lines into a subway tunnel under the campus (an idea the two plans shared) and closing Woodland, Locust Street, and the north–south streets that intersected the campus; Locust Walk would be the main campus thoroughfare. “The University will ultimately would cover the area bounded on the east by 32d Street; on the west by 40th Street; on the north by Walnut Street. Hamilton Walk, below Spruce Street, would be the southern boundary,” according to a statement of the plan’s highlights, which also included construction of a capacious new library in the historic core.

The Martin Plan had three noteworthy components that failed to leave the drawing board: construction of a 30-story tower in the heart of the campus at 36th and Locust, to emulate the University of Pittsburgh’s “Cathedral of Learning”; demolition of the splendid Industrial Age University Library, architected by Frank Furness in the 1890s (now an historic architectural landmark), to afford an extension of Locust Walk to 34th Street; and construction of a women’s campus between 38th and 40th streets, from Walnut to Spruce.[5]