Federal- and State-Funded Urban Renewal at the University of Pennsylvania

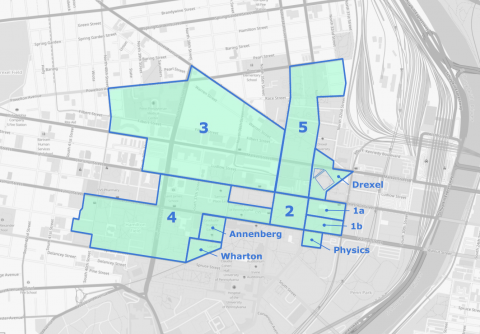

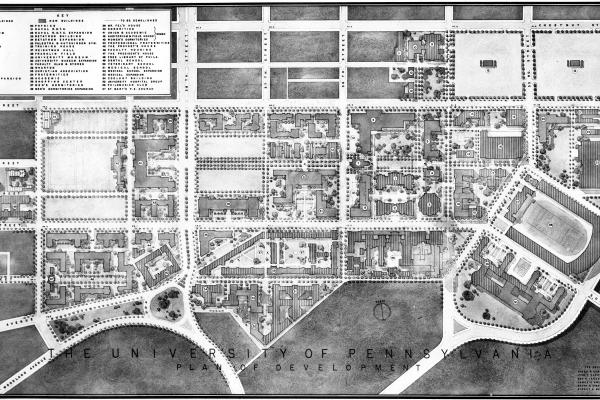

In the 1960s, the University expanded west and north in Redevelopment Authority Unit 4, drawing upon both federal and state urban renewal building funds.

In the 1960s, Penn’s campus expansion west and north of the historic core around College Hall was served through the eminent-domain activity of the Redevelopment Authority in Unit 4. The University received urban renewal building funds from the Pennsylvania General State Authority and the state’s Higher Education Facilities Authority, the latter agency helping to build the West Campus’s superblock of high-rise dormitories. Section 112 of the Federal Housing Act of 1959 gave urban universities wide latitude to redevelop commercial properties in the immediate campus area—in Penn’s case, Walnut Street.

Penn first benefited from federally funded urban renewal in the construction of a women’s residential hall in Philadelphia Redevelopment Authority (RDA) Unit 2, later named Hill House, now Hill College House, which opened in 1960. (The trustees abandoned the Martin Plan’s proposal for a separate women’s campus.) Penn’s agreement with the city committed the University to build other dormitories in the unit, an agreement it would not honor until 2015, when it opened New College House, which spans Chestnut between 33rd and 34th streets and wraps around the corner at 34th and continues down to Woodland Walk—55 years after Hill Hall opened. The massive field adjoining Hill Hall—Hill Field— would stand vacant of new buildings until the School of Arts and Sciences opened the McNeil Center for Early American Studies in 2005. In the mid-1970s, Edmund Bacon, Philadelphia’s legendary city planner, called the use of Hill Field as a campus parking lot and recreation field “a capricious and irresponsible utilization of a space after such destruction.”[1]

Penn received its initial impetus for a westward expansion of the campus from the Pennsylvania General State Authority (GSA), which was established in 1949 to assist land-grant colleges and amended in 1956 to include “universities receiving state aid.”[2] The GSA had power of eminent domain to acquire properties for clearance, convey them to state-supported universities, and put up new buildings at virtually no cost to the institutions. This arrangement lasted until 1963; thereafter, the universities had to pay a 6-percent interest charge on new buildings—still a deal for the institutions. As Penn’s Veterinary School received state funding, the wider University qualified for the GSA bonanza, its legal status as a private university notwithstanding.[3]

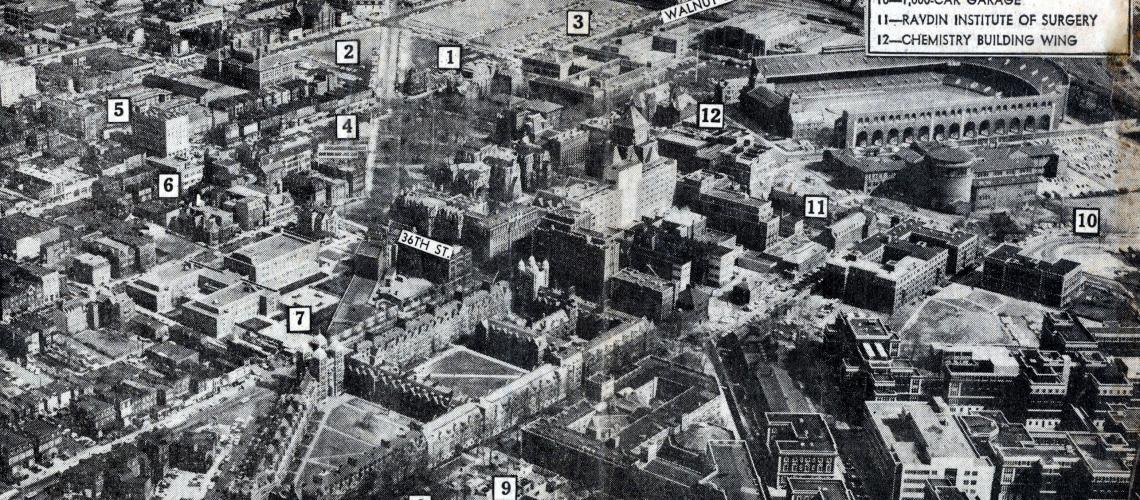

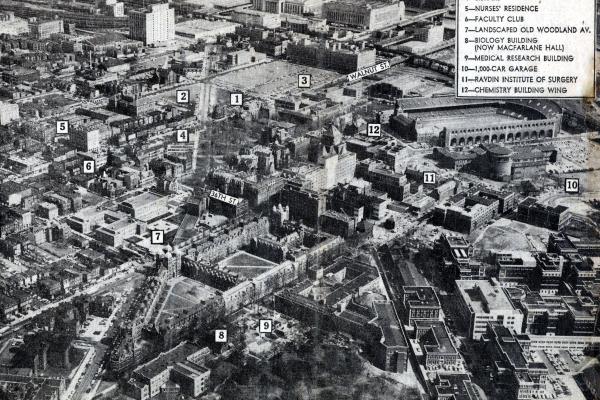

In the 1960s and early 1970s, the GSA’s exercise of eminent domain and its financial largesse enabled Penn to put up 19 new buildings, including the two new libraries (see above) and humanities and fine arts buildings in the historic core, and a new social science center in blocks west of the core surrounding Locust Street, an area condemned as blighted and bulldozed by the Redevelopment Authority. Between 1966 and 1972, GSA-funded buildings for sociology and economics, political science, education, psychology, and social work rose in the nascent west-central campus. Completion of the west-central campus, development of a new commercial zone on Walnut Street, and development of the west campus in blocks beyond 38th Street would await an infusion of federal urban renewal dollars into RDA Unit 4. [4]

The 1959 Federal Housing Act was yet another bonanza for Penn. Section 112 of the Act, which was largely shaped by university planners acting lobbyists for Penn, the University of Chicago, and New York University, gave urban universities nationwide a virtual blank check to ally with local redevelopment authorities to clear swaths of city blocks for institutional expansion and commercial redevelopment in campus areas—largely at federal expense. Penn used Section 112 to complete the west-central campus, with a new building for the Wharton School, at 37th and Spruce streets; and to acquire most of the commercial blocks of Walnut between 34th and 40th streets. All these blocks were included in RDA Unit 4. Also in Unit 4 were the blocks between 38th and 40th streets from Walnut to Spruce, which were earmarked as Penn’s west campus—the so-called Superblock, now Hamilton Village. In the Superblock, the Redevelopment Authority conveyed the properties to the Pennsylvania Higher Education Facilities Authority (HEFA), which built three high-rise and three low-rise dormitories for the University. Penn’s obligation was to make semiannual payments to HEFA on an amortized basis for forty years, after which the University would own the buildings.[5]

With the opening of a pedestrian bridge across 38th Street on Locust Walk, the modern physical campus was completed in 1973, with all schools and departments located on a single, contiguous campus. It remained for Martin Meyerson’s administration to landscape this parklike though unbarricaded enclave, whose walkways opened into West Philadelphia.[6]