The West Philadelphia Initiatives

Part of

At the turn of the Millennium, the University of Pennsylvania, under President Judith Rodin, orchestrated the West Philadelphia Initiatives, a proactive, multipronged strategy to improve social and economic conditions in Penn’s neighborhood of University City.

Between 1996 and 2002, the University of Pennsylvania, under President Judith Rodin, implemented the West Philadelphia Initiatives. This multipronged, proactive strategy, unprecedented for an American university, included innovative programs in five areas deemed essential for stabilizing social and economic conditions in Penn’s neighborhood of University City: neighborhood safety and cleanliness, housing stabilization and reclamation, neighborhood retail development, West Philadelphia purchasing and hiring, and public education investments.

Judith Rodin, Sheldon Hackney’s successor as Penn’s president, arrived on the campus in the summer of 1994 to confront the fatal shooting of a Penn doctoral student by black teenagers near the corner of 48th and Pine streets. Rodin’s response was to ratchet-up the size of the campus police force and to string blue-light emergency telephones, among other reactive measures, around the campus. It took another murder to spur her to move rapidly with an agenda of multipronged, proactive measures: the stabbing death of a Penn researcher on Halloween night, 1996, on the block of 43rd and Larchwood. [1]

Between 1996 and 2002, Rodin’s West Philadelphia Initiatives[2] developed programs in four domains of “urban revival” (her term for her style of urban renewal):

- Neighborhood safety and cleanliness

These programs were conducted under the auspices of the Penn-initiated University City District, a non-profit, special-services consortium involving University City’s higher education institutions—Penn, Drexel University, and Philadelphia College of Pharmacy and Science (now University of the Sciences in Philadelphia)—the Penn Health System, the University City Science Center, the U.S. Post Office, Amtrak, and Children’s Seashore House, with the heaviest concentration in three neighborhoods west of Penn—Spruce Hill, Garden Court, and Cedar Park:

- UCD Ambassadors—patrols of unarmed, roving “safety ambassadors” on bicycles, working in effect as town watches.

- UC Brite—street-level lights on properties, paid and installed through a matching-fund arrangement with local homeowners and landlords.

- UC Green—public-space maintenance teams for litter and graffiti removal, planting trees and streetscaping.

- Housing stabilization and reclamation

- Enhanced guaranteed mortgage program with generous financial incentives to encourage Penn faculty and staff to purchase homes in University City.

- Housing program to upgrade 211 apartments west of campus to rent at affordable prices to moderate-income families and individuals; to purchase 20 houses for rehabilitation and resale at affordable prices to moderate-income buyers; to purchase the massive, Art Deco, General Electric building on the 3101 block of Walnut/3100 block of Chestnut and arrange a ground-lease contract with a Philadelphia developer to convert the industrial building to 282 luxury apartments; to arrange other ground-lease contracts with developers to convert marginal properties to luxury apartment buildings—notably, the Hub, at 40th and Chestnut; the Radian, in the 3901 block of Walnut; and Domus, at 3401 Chestnut.

- Neighborhood Retail Development

Rodin and her leadership team, headed by Penn’s executive vice-president, John Fry (a future president of Drexel University) left a visible imprint on University City’s landscape in this commercial domain. Through ground-lease arrangements with assorted developers, the Rodin administration orchestrated major retail activity on 40th Street: an avant-garde cinema complex (Bridge, now Rave), with two adjoining upscale restaurants, on the southwest corner of the once-troubled intersection of 40th and Walnut; a large, retro-futuristic, street-level food store, Fresh Grocer, with an above-street parking garage, replacing the eyesore University parking lot on the northwest corner of 40th and Walnut; upgraded, student-oriented retail businesses and eateries on 40th between Walnut and Locust.

Also in the list were new upscale restaurants in the Hub and Radian apartment buildings, two upscale restaurants and a café in Penn’s new hotel/bookstore complex at 36th and Walnut; and high-end retail operations in the latter venue and the Domus complex.

- West Philadelphia Purchasing and Hiring

Rodin expanded a program “Buy West Philadelphia,” originated by Sheldon Hackney. The University purchased tens of millions of dollars in supplies from West Philadelphia vendors; and it had contracts for construction projects with minority- and women-owned companies in the amount of $134 million. The University employed a total of about 3,000 West Philadelphia residents in its offices, hospitals, and service departments.

- Public Education Investments

Rodin acted on proposals she inherited to create a high-quality, university-assisted, pre-K–8, public school in partnership with the School District of Philadelphia and the Philadelphia Federation of Teachers. Rodin and her leadership team understood pragmatically that if middle- and upper-middle-class families were to purchase homes in University City neighborhoods west of campus, they would need the assurance of such a school. The Graduate School of Education played the lead role in organizing the three committees (education, facilities, and community) that planned the new school. The Sadie Tanner Mossell Alexander Partnership School, named for a distinguished African American Ph.D. and law graduate of the University, opened in a sparkling new building on the Penn-owned former grounds of the Philadelphia Divinity School, on the block bounded by 42nd, 43rd, Locust, and Spruce Streets. Penn leased the property to the School District at a nominal cost and the School District paid the construction costs and owned the new building. The University promised to provide $1,000 per child per year above the School District’s annual per-pupil expenditure—this to ensure small class sizes and ample resources. Known by its short name, the Penn Alexander School opened in 2002 and soon achieved a record as one of the city’s highest performing schools.

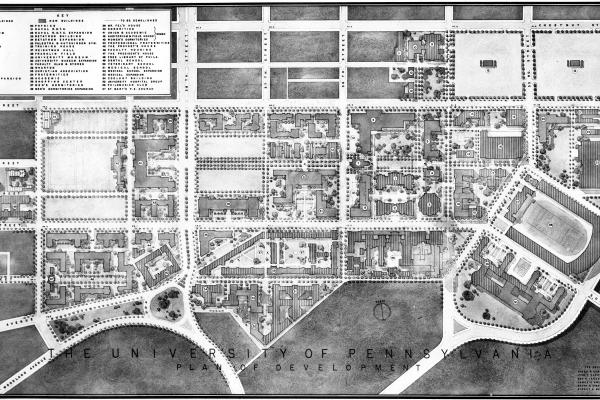

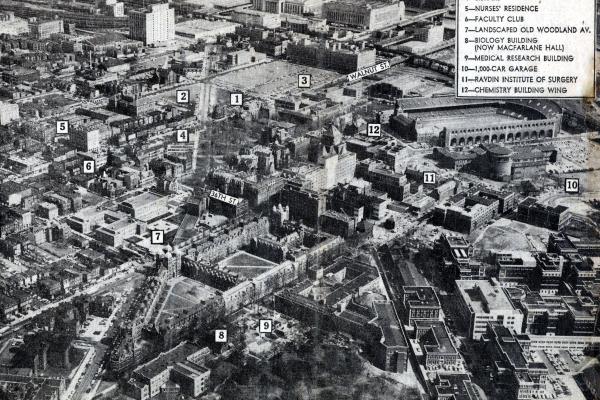

The West Philadelphia Initiatives, combined with Rodin-era landscaping projects in the west campus (Hamilton Village) and on Woodland Walk at Hill Field, brought to fruition the urban renewal program begun decades before in RDA Unit 2 and 4. Rodin and her leadership team raised few community hackles rolling out the West Philadelphia Initiatives, which were negotiated with political and business leaders. They had the luxury of redeveloping properties that were already in Penn’s real-estate portfolio, for the most part properties acquired through urban renewal in the 1960s.

In the Rodin era, Penn expanded its campus, for the most part without controversy. Unlike the 1960s, this time the expansion was toward the Schuylkill on uninhabited properties. The Penn Health System/HUP complex put up new clinical buildings across from HUP on the east side of Convention Avenue, a venue that, in combination with buildings of the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, took on the appearance of a city-within-the-city. Penn also acquired a undeveloped land from the U.S. Postal Service south of 31st and Walnut streets—and area bounded by three rail lines: SEPTA’s regional railway, the High Line (a freight line), and Amtrak’s Northeast Corridor. Rodin’s successor, Amy Gutmann, commissioned development of a parkland in the dismal “Postal Lands.” In 2011, Penn Park opened as a large, environmentally engineered greenspace for tennis, softball, soccer, and lacrosse; its its paths and picnic areas were open to the public.