Alienation and Drift in Penn’s Community Relations

Part of

In the 1970s, the University of Pennsylvania turned inward from West Philadelphia, unable and unwilling to restore its frayed community relations in the face of an unprecedented rise in violent crime.

Penn’s alienation and drift away from West Philadelphia began in the 1970s, when the University experienced turbulent campus politics, confronted a severe budget crisis, and lacked both the funds and the will to help restore its frayed community relations. At the same time, Penn faced an unprecedented rise in violent crime on the campus and its peripheral streets. This situation only worsened in the 1980s with the onset of West Philadelphia’s crack-cocaine epidemic.

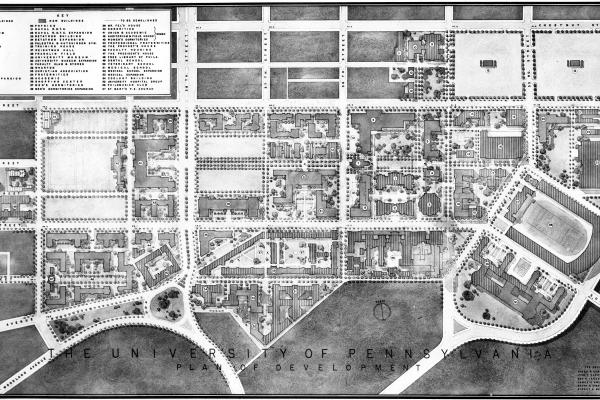

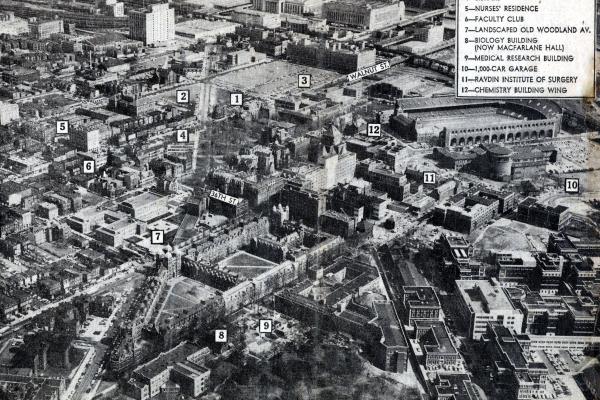

The 1970s saw Penn retreat from involvement in West Philadelphia. Two factors explain drift and alienation in Penn’s relationship with stressed neighborhoods on the borders of University City. First, Penn had no financial resources to invest in community initiatives of any kind. In the 1960s, the University overspent to build the modern campus. It had no money to soften the blow of the next decade’s national economic downturn and soaring energy costs. Consequently, the University accumulated significant budget deficits until 1976 (after which the financial situation steadily improved).[1]

Second, the University confronted an unpreceded rise, on and around the campus, in so-called index crimes—notably, rape, robbery, and aggravated assault—which contributed to “a climate of fear and suspicion” directed toward African Americans in West Philadelphia. By the end of the decade, Penn had a strengthened police force and an improved financial picture, but no political will for engagement in West Philadelphia. Penn’s president from 1970–1981, Martin Meyerson, was too distracted by turbulent campus affairs to invest in community relations. Consequently, the campus community and the area’s African American community continued to eye each other with mutual distrust.[2]

Sheldon Hackney, president from 1981–1993, also faced the urban crisis on Penn’s doorstep. The second half of his administration was marked by a rising tide of crime and violence stemming from the citywide (and national) crack cocaine epidemic. The Daily Pennsylvanian tracked 22 serious incidents on or around the intersection of 40th and Walnut streets from the fall of 1987 to the spring of 1989. Two corner “anchors” at the intersection were Burger King and McDonald’s (fast-food) franchises; another corner fronted an eyesore University parking lot. Headlines proclaimed: “Crime Wave Hits Area Surrounding 40th and Walnut,” “40th Street Has Violent History,” “Under the Golden Arches: Murder, Robbery, Stabbings,” “3 Students Stabbed; 1 Critically Wounded,” “Four Robbed at Gunpoint off 40th Street,” “U. Student Shot on 40th Street.” The night of 1 September 1990 saw the deadliest incident, which Sheldon Hackney sadly noted in his journal: “Last Saturday four black teenagers were gunned down as they say in their car at midnight at 40th and Sansom, near the busy corner of 40th & Walnut where Lucy [Hackney’s wife] and I were just minutes after the shooting. Two died & two are in the hospital.”[3]