Collateral Damage in Unit 3

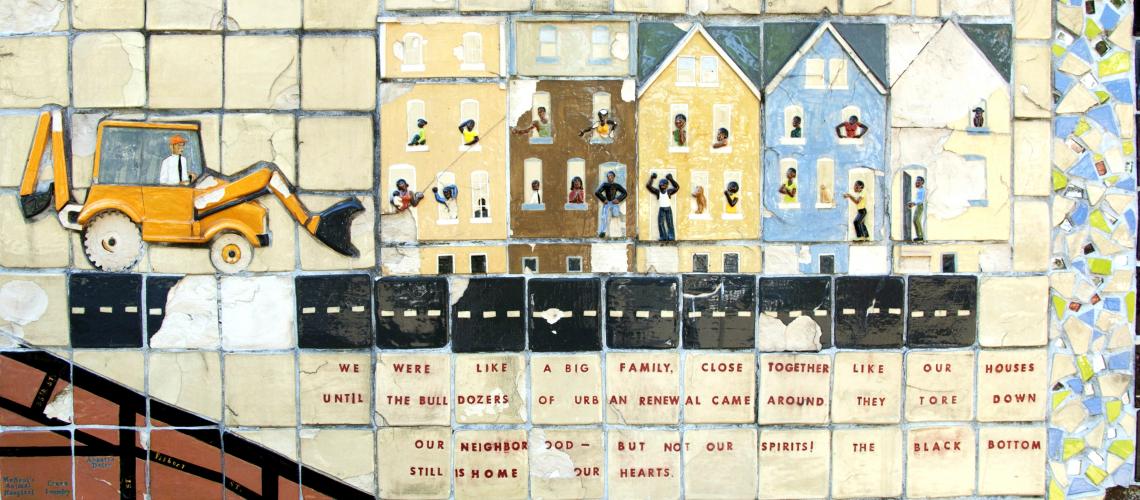

The University of Pennsylvania’s role in the creation of the University City Science Center in RDA Unit 3, a working-poor, majority-African American neighborhood known locally as the “Black Bottom,” severely damaged its community relations for decades to come.

In the late 1960s, the West Philadelphia Corporation, a non-profit coalition of West Philadelphia “higher eds and meds” and a surrogate for the University of Pennsylvania, redeveloped RDA Unit 3 in the Market Street area and recruited the University City Science Center to fill the core of the unit. That large-scale project and the Science Center’s proposed affiliate, University City High School, necessitated the leveling of a working-poor, majority African American neighborhood known locally as the “Black Bottom” and displaced its residents. Penn’s role in the Science Center severely damaged its community relations for decades to come.

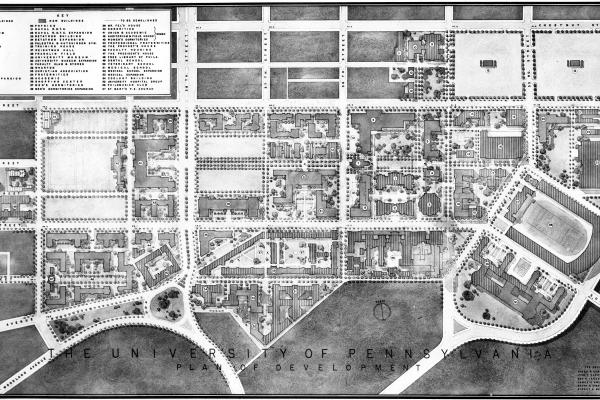

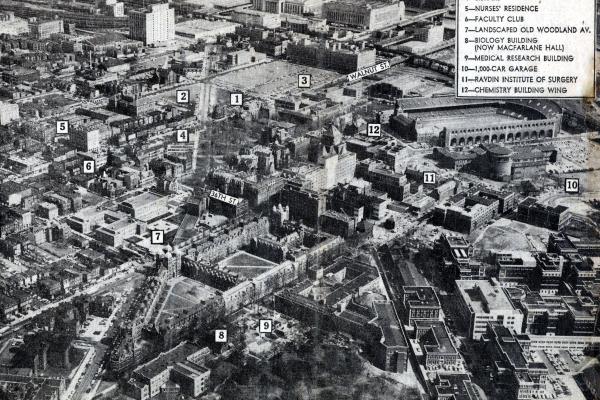

In the 1950s, University planners spoke of the need for “compatible” neighborhoods on the University’s boundaries. A neighborhood of concern to the University was a swath of blocks several blocks north of the campus in the Market Street corridor. This neighborhood, whose population was predominately African American and working poor, was known locally as “Black Bottom.” The planners came to regard Black Bottom, a neighborhood in the throes of physical decline, as a threat to the University.

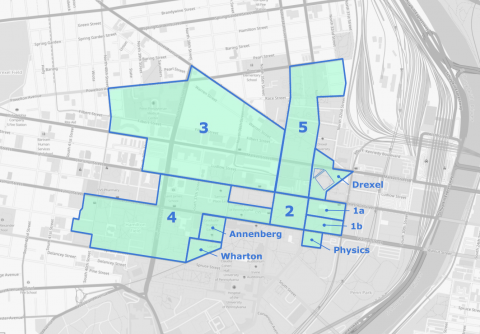

As Penn had no legal writ for urban renewal in the Market Street corridor, it would have to pull strings with the city to get a sphere of influence north of the campus. Regarding the University’s wellbeing as critical to Philadelphia’s future and recognizing its need for “compatible” neighborhoods, the Redevelopment Authority created Unit 3—an urban renewal zone that extended from Powelton and Lancaster avenues south to Chestnut Street between 34th and 40th streets. The City Council and City Planning Commission designated these blocks as blighted, and the RDA condemned them for urban renewal.

The organization that controlled the redevelopment of Unit 3 was the West Philadelphia Corporation (WPC), which was organized in large part to serve Penn’s interests throughout the eastern sector of West Philadelphia. Its main role was to act as the University’s surrogate to ensure the attractiveness, stability, and vitality of all the neighborhoods that bordered the University. In Unit 3, the WPC acted to build a sphere of influence for the University. Anticipating positive ripple effects for their own campuses, Drexel and the other WPC partners acceded to Penn’s domination. The WPC’s strategy in Unit 3 was to recruit scientists and engineers, R&D components of major industries, and investors to build the University City Science Center, the nation’s first urban research park, whose home was “University City,” the WPC’s brand name for the City Planning Commission’s University Redevelopment Area.[1]

Racial politics flared over the RDA’s displacement of 2,653 people in Unit 3 in advance of the Science Center. Roughly 78 percent of the residents who were forced to relocate were African Americans, for the most part renters. The RDA and the WPC turned deaf ears to the protests and acted with hubris and insensitivity to the trauma inflicted by the displacements. By the end of 1967, the Market Street corridor had been leveled for construction of the Science Center and its proposed affiliate, University City High School. The Science Center was headquartered in an existing building on Market Street and new construction along the corridor was underway.[2]

In February 1969, some 800 demonstrators, mostly Penn students and their allies from area colleges and universities, occupied College Hall, staging a six-down sit-in to protest (belatedly) Penn’s involvement in the Science Center, the Science Center’s alleged Vietnam War-related research contracts, and Penn’s role via the WPC in the Black Bottom displacements. Pressure by the demonstrators compelled the Science Center’s board of directors to forswear any present or future research contract that might endanger human wellbeing. Another outcome of the sit-in was the Penn trustees’ promise of transparency in dealing with community members regarding plans for any future expansion of the campus.[3]