“The Audubon Theatre and Ballroom, generally referred to as the Audubon Ballroom, was a theatre and ballroom located at 3490 Broadway and West 165th Street in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City. It was built in 1912 and was designed by Thomas W. Lamb. The ballroom is noted for being the site of the assassination of Malcolm X on February 21, 1965. It has been used as a vaudeville house, a movie theatre, a synagogue, and a meeting place for trade unions and political activists. It is currently Columbia University Medical Center's Lasker Biomedical Research Center (background) of the Audubon Business and Technology Center and the Malcolm X and Dr. Betty Shabazz Memorial and Educational Center (foreground).”

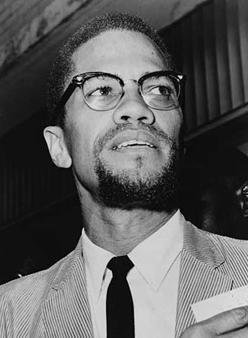

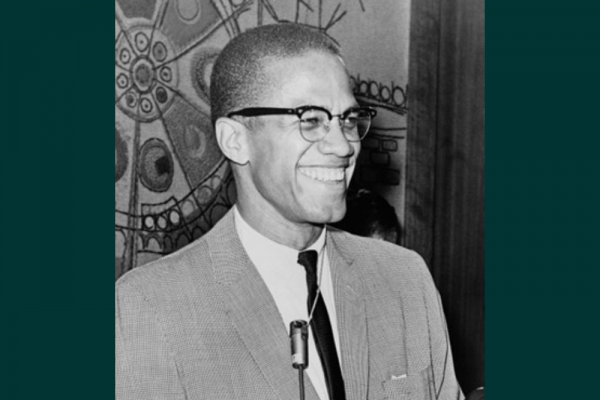

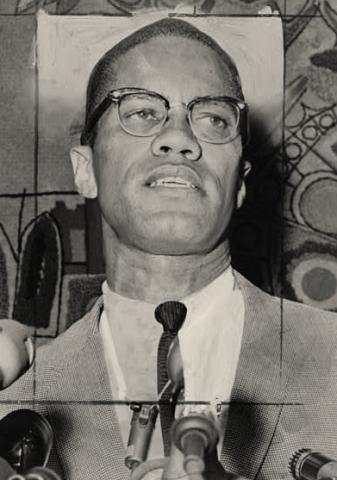

Malcolm X is the second iconic civil rights activist with an imprint on West Philadelphia. He belongs to a radical civil rights tradition that links him with Paul Robeson and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. Part IV looks at Malcolm’s break with Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam, his turn to Pan-Africanism, and the events leading to his assassination at Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom.

In March 1964, Malcolm X publicly broke with the NOI to form the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) and his religious branch, Muslim Mosques, Inc. (MMI). This eventful year included Malcolm’s pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca, his conversion experience, and several months spent in Africa and the Middle East studying orthodox (Sunni) Islam and conferring with leaders of post-colonial nations. His public repudiation of Elijah Muhammad and rejection of NOI “truths” formed the backdrop of his assassination by NOI operatives in Harlem on 21 February 1964.

By 1963, after 12 years of unquestioned devotion to Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm X was having serious doubts about the Messenger, whose philandering ways and fathering of illegitimate children were confirmed by the Messenger’s son Wallace D. Muhammad. Wallace had long since rebelled against his father to follow the practices of Sunni Islam, the largest branch of Islam. In March 1964, Malcolm announced his split with the Nation of Islam (NOI). He had abandoned his belief in W.D. Fard as Allah and Elijah Muhammad as his Messenger. But the Messenger’s organizational strength was superior to Malcolm’s. Elijah Muhammad was able to lure a young Cassius Clay, the world heavyweight boxing champion who had converted to Islam, from Malcolm and rename him Muhammad Ali. By this time, NOI soldiers were plotting Malcolm’s assassination.

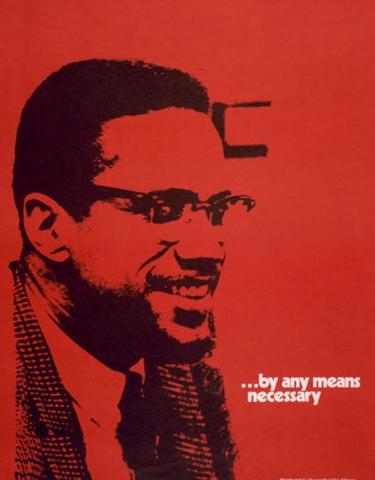

Right after the split, Malcolm began to organize the Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU) and his religious branch, Muslim Mosques, Inc. (MMI). In some ways emulating his parents’ embrace of the Garvey movement, Malcolm advocated a struggle for Black unity on a global scale—one to draw inspiration from the African independence movement. On his home ground in Harlem, in one of his most famous speeches, “The Ballot or the Bullet,” Malcolm revealed his intention to recast the movement for Black civil rights as a global insurgency for Black power. He now embraced voting rights and voter education as practical tools for achieving this broader, more revolutionary agenda. Appalled by the anti-Black violence inflicted on civil rights demonstrators, during the spring-summer 1963 Birmingham protests and the September bombing of a Birmingham church that killed four black children, Malcolm advocated for Black self-defense to meet violence with violence. His stance was publicly rejected by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

Pan-Africanism and Sunni Islam were uppermost in his thoughts in the last year of his life. Malcolm’s pilgrimage (hajj) to Mecca, the spiritual center of orthodox Islam, was transformative. In Mecca he encountered color variations among Muslims—including blue eyes, blond hair, and whitish skin—an experience that shattered his belief that white skin and blue eyes were synonymous with Satan and that all white people were devils. After Mecca and visits to Lebanon, Egypt, and Nigeria, Malcolm arrived in Ghana, the spiritual center of Pan Africanism, where he met with and was embraced by American expatriates. Here he expressed admiration for anti-racist whites such as the abolitionist John Brown and the Quakers who directed the Underground Railroad.

On his return to New York in May he publicly charged Elijah Muhammad with fathering six illegitimate children. His life was now in imminent danger. And while he continued to advocate for Blacks’ right to self-defense, he reached out to civil rights leaders advocating for making the struggle for Black equality in America an international cause by taking it to the United Nations. In June he was back in Egypt to make his case to African leaders to join his OAAU’s appeal to the UN on behalf of the American struggle—a case for which he was able only to elicit a weak resolution expressing concern about injustices to “Negro Citizens of the United States,” as opposed to “Afro-Americans.”

Malcolm would remain in Africa for a total of four and a half months, studying orthodox Islam as practiced in Mecca and lobbying individual African leaders who acknowledged him as the representative of 22 million Afro-Americans—although no leader would petition the UN on behalf of his cause. His project to engage the UN and muddy its waters with the U.S. government spurred the FBI director J. Edgar Hoover’s increased surveillance and recruitment of informants to report on Malcom’s activities. Both Hoover and the NOI wanted Malcolm neutralized. One of Malcolm’s security guards was a Black undercover New York police officer whose reports were conveyed to the FBI.

In October 1964, The New York Times published Malcolm’s denunciation of the NOI as a fraudulent, racist, pseudo-religion. And he proclaimed his conversion to Islamic orthodoxy and that faith’s belief in the equality of all human beings before God.

The Chicago hit order, if not directly issued by, no doubt had the approval of Elijah Muhammad. On 14 February 1965, Malcolm’s family’s home in Queens was firebombed, though without injury. Already, there had been several attempts on Malcolm’s life by NOI assassins in East Coast cities and Chicago. The lethal NOI hit, carried out by three gunmen, with the fatal blow delivered by a shotgun, took place at Harlem’s Audubon Ballroom on Sunday, 21 February 1965. It came at a time when Malcolm had loosened his security. Only one of the three shooters was ever convicted of killing Malcolm X; the other two were never adjudicated. Two members of the Harlem mosque who were not at the Audubon that day were wrongfully convicted in the real shooters’ stead and sentenced to more than twenty years in prison; in 2021, the Manhattan district attorney exonerated both.

After Malcolm

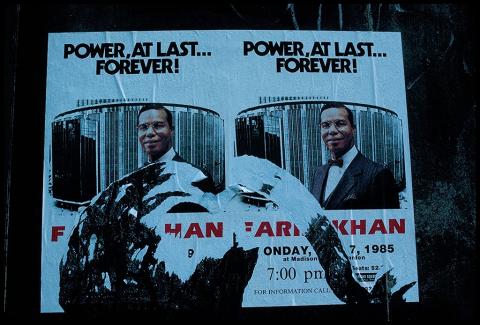

The Nation of Islam fell prey to a schism in the decade following Malcolm’s death. The split in the organization occurred after the death of Elijah Muhammad in 1975. The schism was rooted in Malcolm X’s defection from the NOI, when Minister Louis X, soon to become Louis Farrakhan, publicly denounced Malcolm in spiteful articles in Muhammad Speaks in 1965. Farrakhan also regarded Elijah’s son Wallace D. Muhammad as a traitor to Elijah. Changing his name to Warith D. Mohammed, Wallace sought to steer the NOI toward orthodox Islam and to demythologize the semidivine status of his father and the myth of Yakub. Wallace’s group became the World Community of al-Islam in the West in 1976 and renamed itself the American Muslim Society (AMS) in 1980.1

Following the split, Farrakhan anointed himself Elijah Muhammad’s true heir and the NOI’s national representative. His most important pastorates would be Mosque Maryam, the NOI’s headquarters in Chicago, and Harlem’s Temple No. 7, which Malcolm had founded. Farrakhan’s group formally declared itself The Nation of Islam in 1981. Warith D. Mohammed’s group, the AMS, operated until 1985, when it disbanded. By 1996, Warith and his followers had a discipleship of some 200 plus mosques whose base was entrepreneurially minded African Americans. Warith died in Chicago in 2008. Today, followers of his brand of Sunni Islam comprise only a small minority of Sunni followers nationwide.2 That is certainly the case in West Philadelphia. As for Farrakhan and the NOI, they are described by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC) as a hate group that promotes an anti-white theology; it is accused of anti-Semitism by the SPLC, Anti-Defamation League, and other monitoring groups.3

Farrakhan left his mark on the University of Pennsylvania in the mid-1980s. In the fall of 1986, Farrakhan supporters in the Black Student League, whose head was an NOI disciple, invited him to speak on campus. When university officials refused to provide security, Farrakhan cancelled the speech—although this didn’t prevent shouting matches between NOI supporters and Jewish students who accused Farrakhan of anti-Semitism. After these same officials finally agreed to provide handheld metal detectors, Farrakhan addressed a predominately Black audience, filling Irvine Auditorium, where he avoided incendiary statements and called for self-reliant Black social, economic, and spiritual renewal.4

Farrakhan was the focus of media attention in 1995 as the organizer and leader of the Million Man March on Washington, with an estimated attendance of 837,000 participants (with a 20 percent margin of error; the National Park Service’s estimate was considerably less).5

At this writing (fall 2022), Louis Farrakhan, at age 91, continues to espouse views held by Elijah Muhammad.6

A Note on Sunni Islam & the University of Pennsylvania

Masjid Al-Jamia, at 4228 Walnut St., in West Philadelphia, is a traditional Sunni mosque that serves the city’s largest and most diverse population of Muslims. It offers religious services for the faith’s five daily prayers and the Friday congregational prayers. Also, according to Majid Mubeen, “It has become a lively center for Islamic and Arabic studies and is always teeming with religious activities, from free dinners during Ramadan to Quranic study circles.”7

The mosque was founded in 1988 by the University of Pennsylvania’s Muslim Students Association (MSA). The MSA raised $100,000 to purchase the expansive redbrick building, which dated to 1928. It was built in a Spanish Revival/Moorish style to house the Commodore Theater and was large enough to accommodate audiences of 1,105 moviegoers. By the 1960s, it held sizable audiences for stage performances. During and after the 1960s, religious organizations owned the building, the current one being the Shura (elective consultative council), which administers the mosque. In 2009, the MSA signed over the building to the Shura..8

1. Lawrence H. Mamiya, “From Black Muslim to Bilalian: The Evolution of Movement,” Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 21, no. 2 (1982): 138–152.

2. Ibid.; Ernest Allen Jr. “Religious Heterodoxy and Nationalist Tradition: The Continuing Evolution of the Nation of Islam,” The Black Scholar 26, no. 3/4 (1996): 2-34; “Warith Deen Mohammed,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warith_Deen_Mohammed.

3. “Louis Farrakhan,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Louis_Farrakhan.

4. John L. Puckett & Mark Frazier Lloyd, Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000 (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2015), 197–199.

5. “Louis Farrakhan,” Wikipedia.

7. “Masjid Al-Jamia,” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Masjid_Al-Jamia; Majid Mubeen, “Masjid Al-Jamia: The History of Penn’s Muslim Students Association and the Mosque in West Philadelphia,” Here and Over There: Penn, Philadelphia, and the Middle East, accessed from https://pennds.org/nelc133/exhibits/show/masjidaljamia/msaandmasjidaljamia, 9 March 2022. For a succinct history of Islam and its varied communities of faith in the Greater Philadelphia region, see David M. Kruger, “Islam,” Encyclopedia of Greater Philadelphia, https://philadelphiaencyclopedia.org/essays/islam/.

A Note on Sources for Malcolm X: Indispensable sources for the WPCH articles on Malcolm X are two Pulitzer Prize-winning biographies—Les Payne & Tamara Payne, The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X (New York, 2020); Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (New York, 2011). These biographies provide additions and corrections to The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as Told to Alex Haley (New York, multiple editions since 1966). The most recent authoritative source, also indispensable, is Peniel E. Joseph, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. (New York, 2021), a comparative biography. John L. Puckett & Mark Frazier Lloyd, in Becoming Penn: The Pragmatic American University, 1950–2000 (Philadelphia, 2015), provide an account of Penn’s Farrakhan controversy that is situated in the context of the university’s troubled race relations in the 1980s and early 1990s.

Continue reading Heroic Civil Rights Icons in West Philadelphia

Stories in this Collection

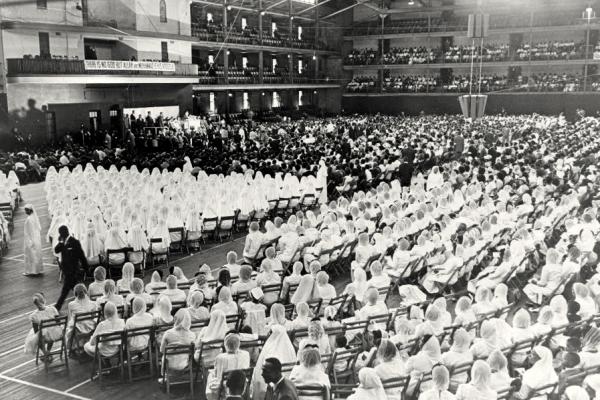

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project. |

![Vintage black and white photo of the Kaaba and Grand Mosque, in Mecca. The exterior of the Kaaba is covered with a large black cloth. It stands in the center of the photo, in front of the Grand Mosque, in the near background. In the far background is a mountain with numerous buildings.]](https://collaborativehistory.gse.upenn.edu/sites/default/files/styles/large/public/Pilgrimage%20to%20Mecca.jpg?itok=xVN0F5_1)