Contemporary aerial view of the Massachusetts Correctional Institution (MCI) at Concord, on Route 2 in Concord, Massachusetts; before 1955 named the Massachusetts Reformatory at Concord, where Malcolm Little was incarcerated for 15 months between 1947 and 1948. Here, influenced by family members, Malcolm had the first inklings of his conversion to the version of Islam practiced by the Nation of Islam

Malcolm X is the second iconic civil rights activist with an imprint in West Philadelphia. He belongs to a radical civil rights tradition that links him with Paul Robeson and Martin Luther King Jr. Part II looks at Malcolm Little’s prison conversion to the version of Islam practiced by the Nation of Islam and his decision to become Malcolm X.

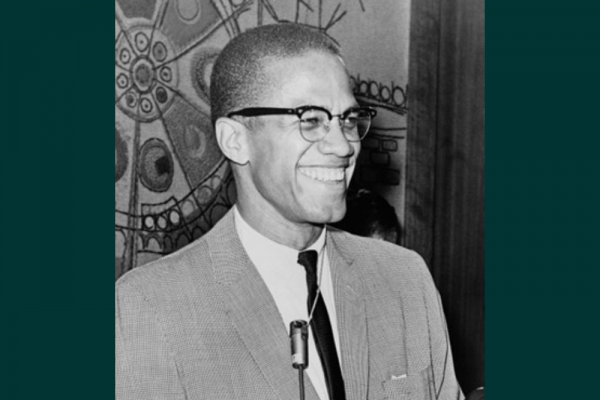

By the end of World War II, Malcolm Little had moved beyond petty crimes to heading a burglary team in Boston and its affluent suburbs. Adjudicated for these crimes, he would spend six years shuffling between different Massachusetts state prisons. Significantly, Malcolm used this time productively to educate himself in prison libraries, where he learned the fundamentals of effective rhetoric and oratory, as well history and philosophy. Malcolm also came under the influence of the teachings of Elijah Muhammad and the Nation of Islam (NOI). His conversion to the NOI was marked by his adoption of the name Malcolm X and his commitment to serve the NOI upon his return to society.

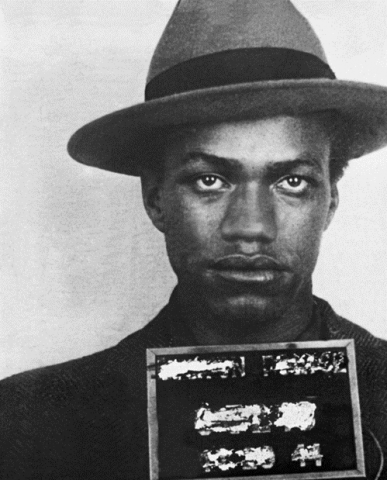

Malcolm managed to avoid military induction by staging a bizarre performance that persuaded the draft board to declare him mentally unstable (indeed psychopathic) and send him a 4F rejection notice. Yet at the same time, he was spiraling deeper into the numbers racket and dangerous behavior fueled by opium and booze. By war’s end Malcolm had moved beyond petty crimes to heading a burglary team in Boston and its affluent suburbs. In the winter of 1946, he was tried and found guilty of multiple felony counts in Middlesex County. He was sentenced to eight to ten years in prison.

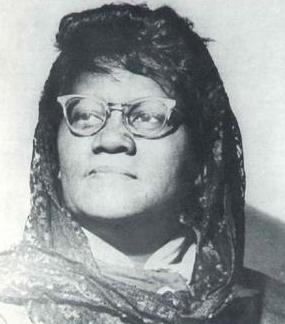

Malcolm was not yet 21 when he arrived at the maximum-security Charlestown State Prison. Tutored by an older, autodidactic jailhouse philosopher, “Bimbi,” Malcolm began to hone his rhetorical gifts and gravitated to the prison library to study wordsmithing. He was looking to the future beyond prison. Sister Ella’s connections helped him transfer from Charlestown to the smaller, medium-security Concord Reformatory (in 1955 renamed the Massachusetts Correctional Institution–Concord), which had a better library than Charlestown’s. Influenced by family members, he first experienced what would evolve into a religious conversion. In Detroit, his older brother Wilfred attended the first meeting of the Nation of Islam (Temple No. 1). Black Muslims believed theirs to be the “natural religion for the Black Man.” For the Little clan, it was a short spiritual leap from the family’s Garveyite roots.

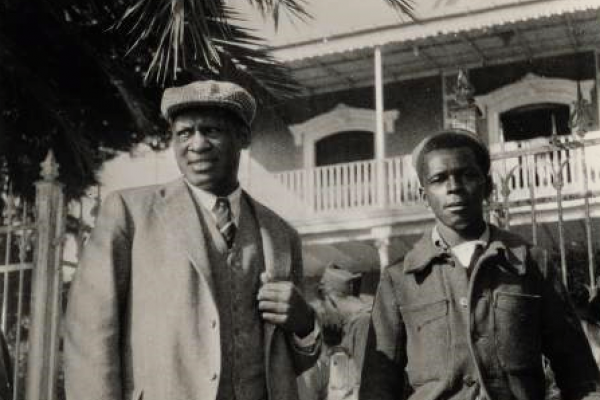

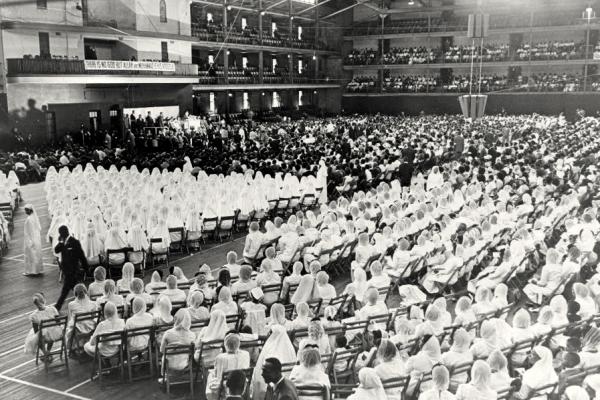

The Nation of Islam (NOI) was founded in Detroit’s Paradise Valley neighborhood in 1930 by Wallace D. Fard (pronounced Fa-ROD). Known also as W.D. Fard, Fard Muhammad, and other names, he was a controversial figure of uncertain ethnic origins with a criminal background. He preached Black exceptionalism and self-pride to the first generation of the Great Migration, offering a counterweight to the scientistic (statistical) racism that clouded white intellectuals’ thinking into the 1930s. Fard touted the virtues of healthy eating, devotion to family, self-reliance, entrepreneurship, and temperance. As for fealty to orthodox Islam, the founder was remiss. Fard invoked Muslim ritual, dogma, and nomenclature in the service of a homegrown religion grounded in anti-white separatism, a distortion of orthodox Islam as practiced in the Middle East.

Fard’s prize disciple and self-anointed successor in 1933, was Elijah Muhammad, born Elijah Poole, a Black migrant from Georgia. In another of the sect’s distortions of orthodox Islam, Elijah Muhammad deified W.D. Fard as Allah Incarnate and anointed himself Allah’s Messenger. Fard preached that Black Americans belonged to the original people of the planet, the Lost Tribe of Shabazz. The NOI origin myth depicted whites as a weak hybrid race created by the Black mad scientist Yakub in his revolt against Allah. As the journalist I.F. Stone noted, in this respect it was no more rationally absurd than the Virgin Birth of Christianity; moreover, “the rational absurdity does not detract from the psychic therapy” that helped NOI followers to achieve psychic uplift, to shed feelings of racial inferiority, to be, in Stone’s words, “fully emancipated.” Succinctly put, the NOI was a homegrown borrowing from Islam expressly adapted to the situation of urban poor Black Americans. As such it was rejected as blasphemy by the major Islamic sects, which adhered to the historic Middle East religion—they did not consider Fard Muhammad to be a new Prophet Muhammad.

In 1948 Malcolm, again through sister Ella’s intercession, was transferred to Massachusetts’ Norfolk State Prison (in 1955 renamed the Massachusetts Correctional Institution–Norfolk), which had a well-stocked library. Now an obsessive reader, he immersed himself in Elijah Muhammad’s teachings, world history and philosophy, and the history of Black enslavement. And he engaged face-to-face with debating teams from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Yale, and Harvard—and honed the world-class polemical skills that would propel his rapid ascent as the nation’s—and later the world’s—foremost Black Muslim advocate. By 1950, Malcolm was calling himself “Malcolm X Little,” the X signifying the lost African family names that were not recorded by the enslavers.

A Note on Sources for Malcolm X: Indispensable sources for the WPCH articles on Malcolm X are two Pulitzer Prize-winning biographies—Les Payne & Tamara Payne, The Dead Are Arising: The Life of Malcolm X (New York, 2020), Manning Marable, Malcolm X: A Life of Reinvention (New York, 2011). These biographies provide additions and corrections to The Autobiography of Malcolm X, as Told to Alex Haley (New York, multiple editions since 1966). The most recent authoritative source, also indispensable, is Peniel E. Joseph, The Sword and the Shield: The Revolutionary Lives of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. (New York, 2021), a comparative biography.

Continue reading Heroic Civil Rights Icons in West Philadelphia

Stories in this Collection

This collection of nine stories explores the ties between Paul Robeson, Malcolm X, and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as heroic civil rights icons who left formidable imprints on West Philadelphia. The collection begins with Robeson, who spent the last decade of his life in West Philadelphia (1966–1976), tracing his meteoric rise to international fame as an incomparable singer and Black actor of stage and screen, his turn to political activism, his international advocacy for social justice for all oppressed people, and his persecution by the federal government during the Cold War. Next is Malcolm X, who as a convert to the Nation of Islam (NOI), overcame his past as an incarcerated street hustler to become a devout acolyte of the Messenger Elijah Muhammad and the NOI’s national spokesperson. Among other temples under his watchful eye was Muhammad Temple of Islam #12 in West Philadelphia. Before his assassination by NOI operatives, Malcolm converted to mainstream (orthodox) Islam and embraced racially inclusive pan-Africanism. Last is King, who at the height of northern racial turmoil in the Civil Rights era, held a major rally in West Philadelphia just as he was entering the radical phase of the last three years of his life. A final synthesis story surveys the common ground shared by these three Civil Rights precursors to the contemporary Black Lives Matter movement and the New York Times' 1619 Project. |